The Newfoundland Railway and the company money of R. G. Reid

By 1885, Canada was linked by rail from Halifax to the coast of British Columbia. Meanwhile, Newfoundland was still struggling to tie its coasts together.

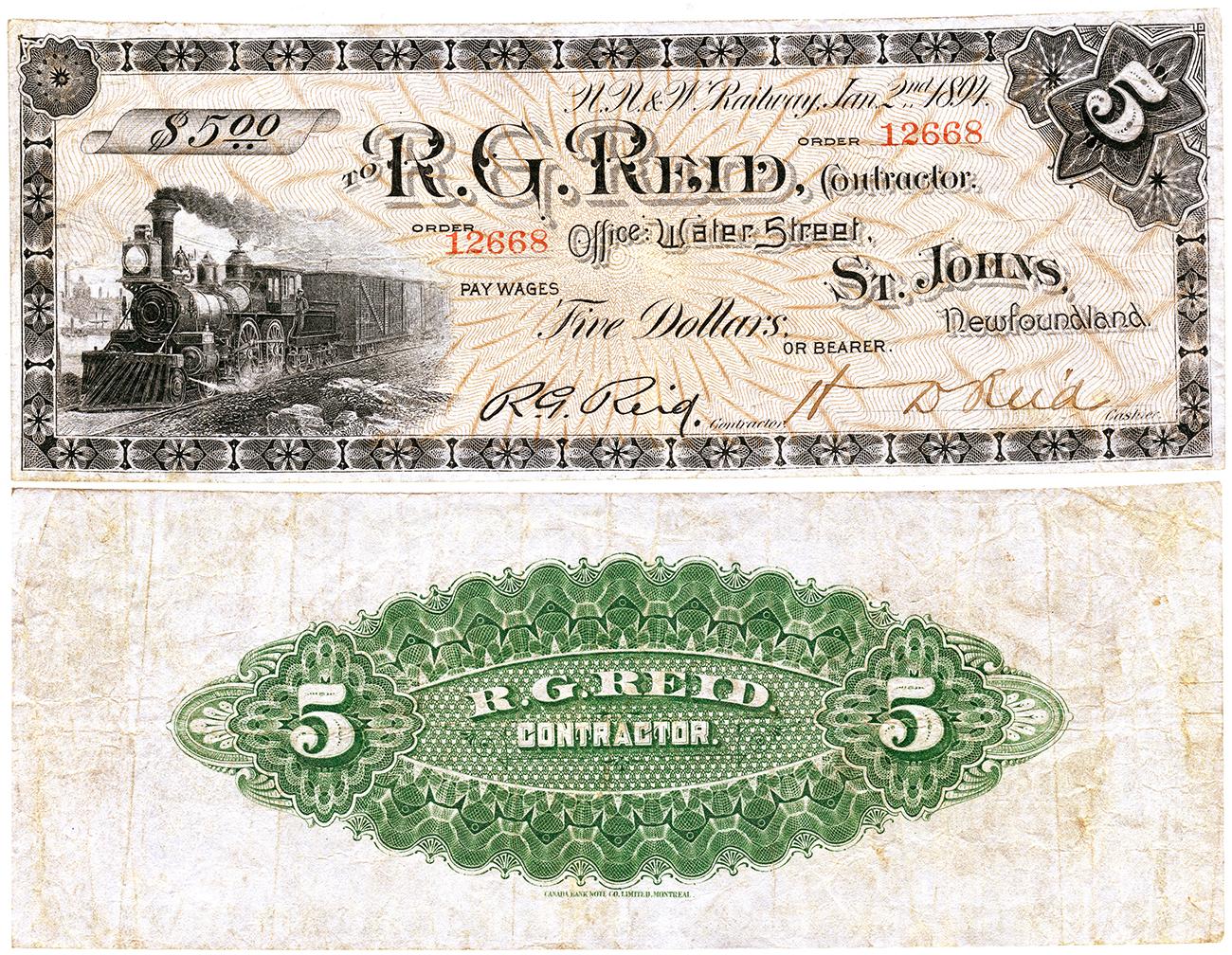

The years that railway builder R. G. Reid spent finishing the Newfoundland Railway were among the most economically disastrous in the province’s history. The railway bankrupted the government and nearly ruined Reid. During the worst of Newfoundland’s 1894 financial crisis, Reid had to find a way to pay his workers. So, he resorted to printing his own money, which his workers could spend at the construction site or redeem for currency at the company’s head office.

Bringing Newfoundland into the age of rail

With the ceremonious driving of the last spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia, on November 7, 1885, the vast expanse of Canada finally had a railway. With the addition of existing rail lines that linked the Maritimes with Quebec and Ontario, a ribbon of steel bound Canada together from Halifax to Vancouver. It took longer to join Newfoundland’s coasts by rail.

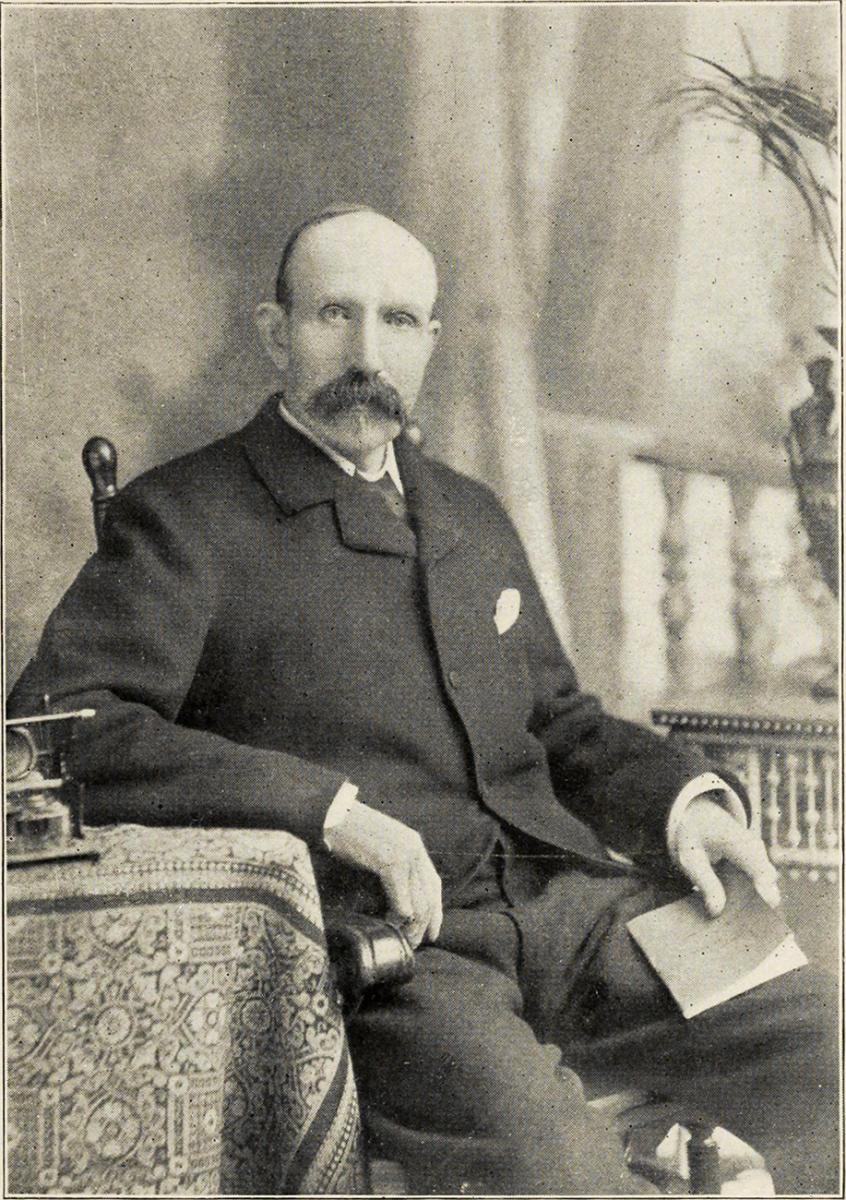

The task of linking the Canadian provinces by rail was accomplished on the dime of wealthy financiers, on the backs of foreign labourers, with the will of the Dominion government and the vision of engineers. One such visionary was Robert Gillespie Reid, a Scottish engineer and self-made businessman. Reid was deeply involved in the linking of the nation by rail: building bridges and laying down track through the inhospitable terrain of the Canadian shield. By 1885, his crowning achievement was the construction of a 137-metre-long tunnel through the impassable Jackfish Bay section of the railway on the north shore of Lake Superior. But building a railway across Newfoundland, a seemingly simpler task, would prove to be a greater challenge for Reid.

The making of King Reid

R. G. Reid was 48 years old when he came to Newfoundland in 1890. He immediately entered into an agreement with the Newfoundland government to complete a stalled project to build a railway running from St. John’s to Port aux Basques. Against his engineers’ advice, Reid chose to run the railway through the middle of the island—covering about 900 kilometres of very rough terrain. He was taking a big gamble. But contracts were signed, and Reid was determined to meet his commitment. He hired 1,800 workers who did all the work by hand. Labourers worked 60 hours a week for $6. They were paid only for the work they completed, and their food, shelter and medical expenses were not covered.

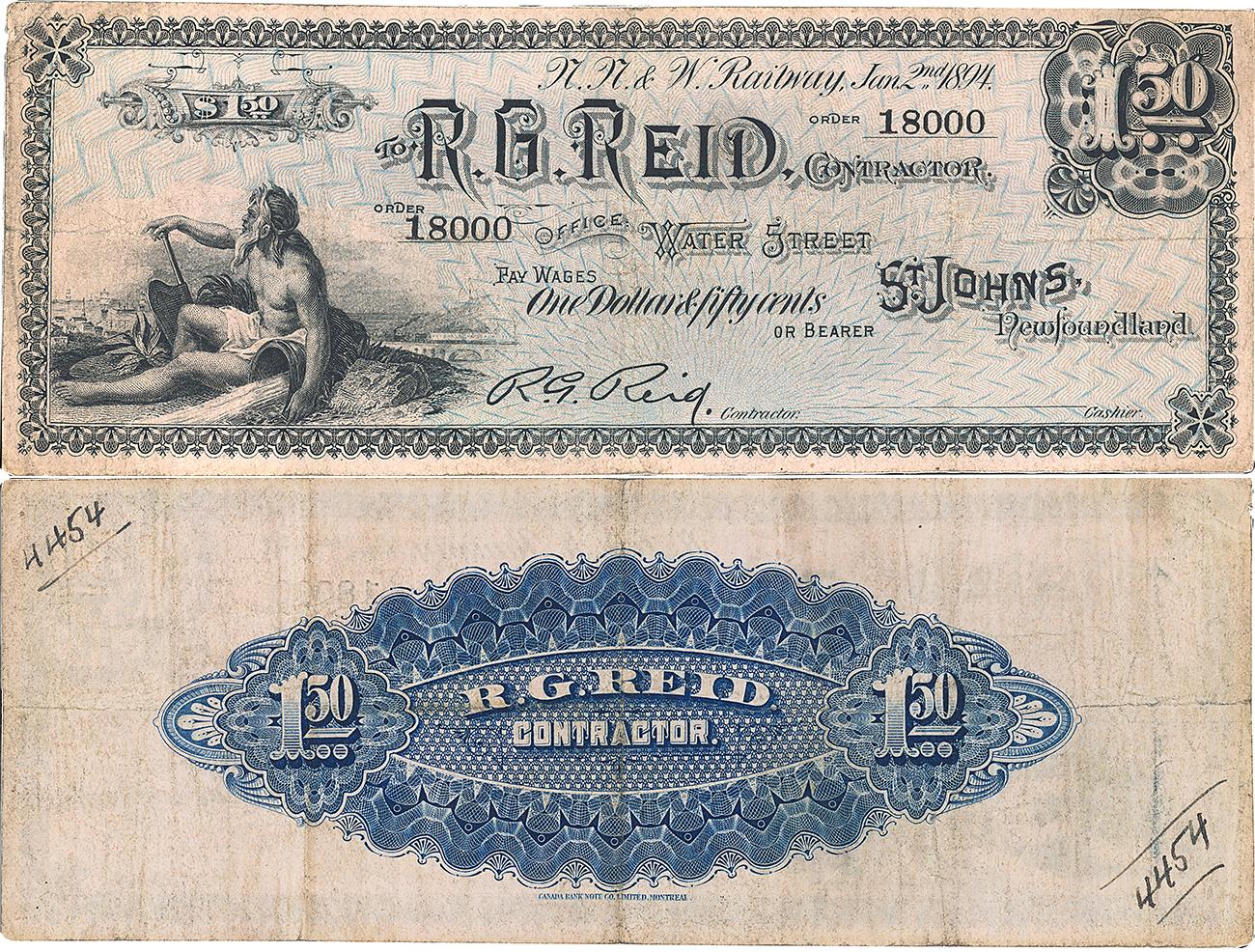

A $1.50 note of the Newfoundland Northern and Western Railway. The only two known examples of this note are both in the National Currency Collection.

1 dollar and 50 cents, scrip, Newfoundland Northern and Western Railway, 1894, NCC 1974.235.141

In May 1893, Reid took over rail operations for the entire province, and the Newfoundland Northern and Western Railway was born. Reid controlled almost 3 million acres of land, becoming the biggest landowner in Newfoundland. And he was more than just a contractor to the government—he was the power behind the government. Increasingly, the Newfoundland government was turning to Reid for financial advice and emergency loans. It was only Reid’s personal presence that staved off certain financial disaster after Newfoundland’s 1894 bank crash when two of its three banks closed in one day.

Of economic crises, failed banks and missed confederations

An economic depression that struck North America in 1892 hit Newfoundland particularly hard. By 1894 credit was hard to find, banks failed, and thousands of citizens lost their savings. Large firms went bankrupt, riots broke out, stores were looted, and the military was called in to restore order. Reid was on the verge of ruin, yet insisted on continuing railway construction. Suffering huge losses, and with no credit or cash resources, Reid issued wage notes to pay his employees. The notes came in denominations of $1, $1.50, $2 and $5. They could be used to buy goods from makeshift storage tents at the construction site. They could also be redeemed for currency at the company’s office on Water Street in St. John’s.

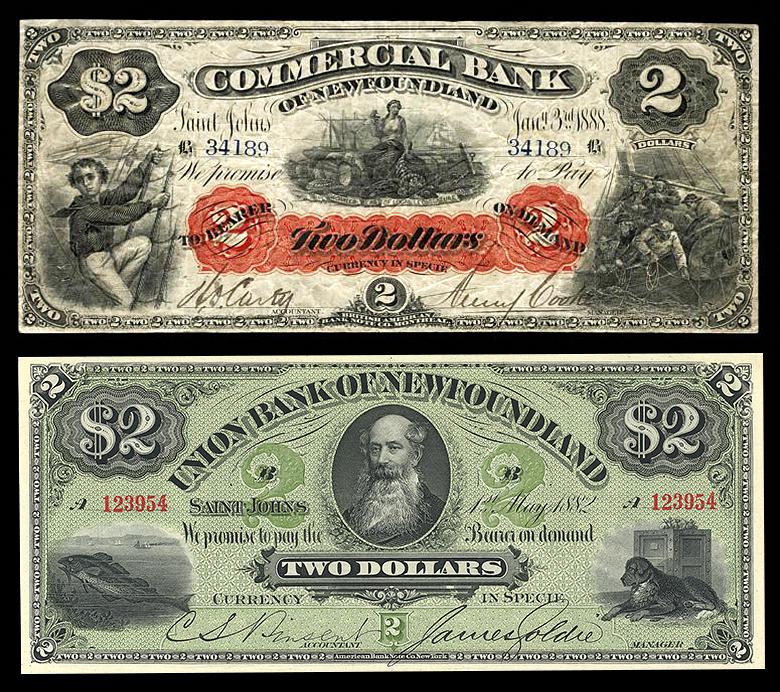

Newfoundland had two homegrown banks operating in 1894. Both collapsed within hours of one another on December 10.

2 dollars, note, Commercial Bank of Newfoundland, 1888, NCC 1964.145.3.

2 dollars, note, Union Bank of Newfoundland, 1882, NCC 1964.37.5

The bank crash of 1894 financially devastated the province. Reid travelled to Montréal with then prime minister of Newfoundland, Robert Bond, to find support from financiers and avoid default on the province’s debt payments. But Reid’s motives were not entirely selfless; he held $4 million in government bonds and they were fast becoming worthless. Reid had to keep the Newfoundland government solvent so that it could pay the debt owed to him. He managed to convince the Bank of Montreal to open a branch on the island at a time when there was no negotiable currency in circulation.

In 1895, another Newfoundland delegation, including Reid, went to Ottawa, this time to discuss terms of joining Confederation. But the government of Canada refused to accept Newfoundland’s debt, which was mainly the cost of the railway. The irony is that it had offered to finance the railway 10 years earlier, but Newfoundland had refused.

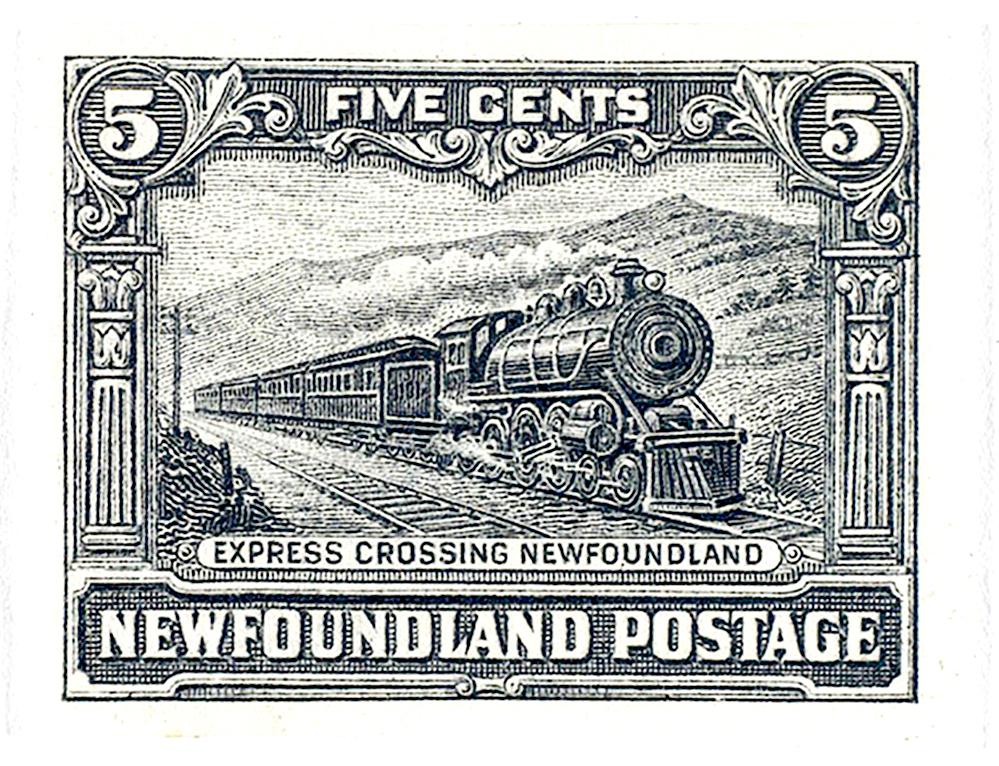

The “Newfie Bullet” was scheduled to take roughly a day to travel from Port aux Basques to St. John’s—when it was on time. 5 cents, stamp, Newfoundland, 1929, Library and Archives Canada

The Reid Deal: a big deal

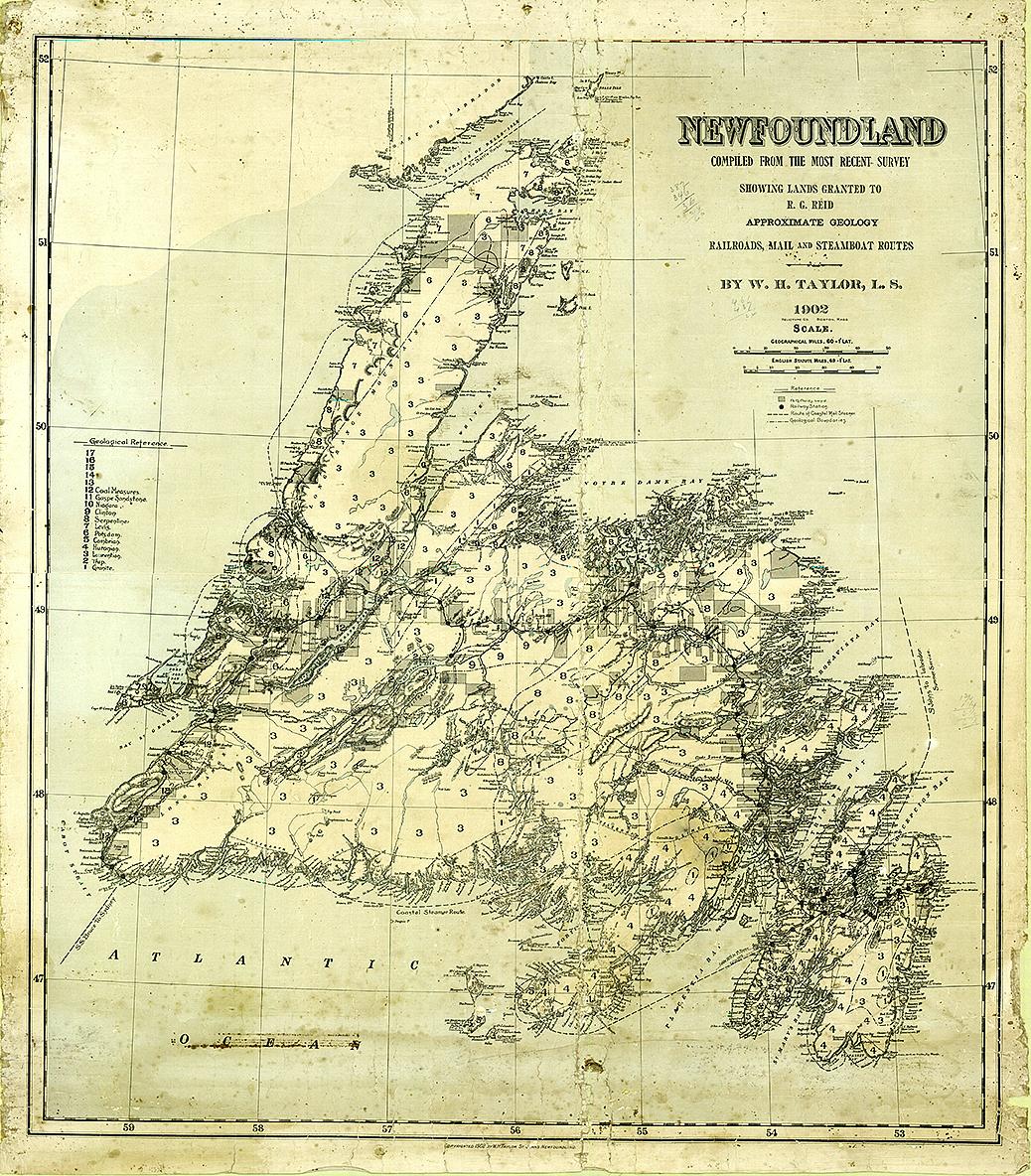

This map shows Reid’s railway, and steamboat and mail routes. The grey boxes indicate Reid’s enormous land holdings. W. H. Taylor, 1902, Queen Elizabeth II Library Map Room, Memorial University of Newfoundland

In the spring of 1898, the rail line from St. John’s to Port aux Basques was complete. The train was referred to as the “Newfie Bullet,” a tongue-in-cheek name, given the train’s average speed of just 28 kilometres an hour. The train was also called the “Streak of Rust.” Assuming it didn’t get stuck in the snow or derail, the Bullet could be expected to make the trip in roughly 30 hours (although sometimes it failed to arrive at all). By the time the Cross-Country Express was operational, the government was already bankrupt. Interest payments and unpaid debts ate up 70 percent of government resources. In a desperate attempt to pay the bills, and avoid any new ones, the resources and future of the entire island and its people were virtually given away, in what became known as the Reid Deal.

Newfoundland’s Conservative government, led by James Winter, offered to sell the railway to Reid for $1 million. As part of the deal, Reid would operate the railway for 50 years. Signed in 1898, the Reid Deal made Robert Gillespie Reid the most powerful man in Newfoundland. He owned the railway, the telegraph, the mail steamers, the hydro-electric system and one in six acres of land, with full mineral rights. He was invested in so many concerns, from skating rinks to the St. John’s tramway, that it was alleged he was invested in the provincial legislature itself.

Railway enthusiasts love this note for its engraving of the original “Newfie Bullet,” a Hunslet 4-4-0 locomotive. 5 dollars, scrip, Newfoundland Northern and Western Railway, 1894, NCC 1972.204.1

Reid’s dying wishes

As Newfoundland struggled for its financial survival, Reid’s health was failing. In 1905, he offered to sell his Newfoundland Railway to the provincial government, but prime minister Robert Bond turned him down. Reid died in Montreal in 1908. His will directed that his interest in the Reid Newfoundland Company was to be "…realized and disposed of as soon as possible" and he advised his sons not to "invest any part of my estate in any new enterprise or in any speculative or hazardous investments in Newfoundland or elsewhere."

The shrewd Scot kept his word and built the railroad, but the railroad got the best of him in the end.

References and further reading

- Cuff, Robert. 1994. “Sir Robert Gillespie Reid.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. (www.biographi.ca/en/bio/reid_robert_gillespie_13E.html, accessed June 6, 2019)

- Rowe, F. C., J. A. Haxby and R. J. Graham. 1983. The Currency and Medals of Newfoundland: Volume 1, Canadian Numismatic History Series. Toronto: J. Douglas Ferguson Historical Research Foundation.

- Harding, Les. 2008. The Newfoundland Railway, 1898–1969: A History. London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Hiller, James. 1978. “The Railway and Local Politics in Newfoundland, 1870-1901,” in James Hiller and Peter Neary, eds., Newfoundland in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Essays in Interpretation (Toronto).

- Korneski, Kurt. 2008. “Race, Gender, Class and Colonial Nationalism: Railway development in Newfoundland, 1881-1898” in Labour/Le Travail, 62 (Fall, 2008), 79-107.

The Museum Blog

The Adventure of Exhibit Planning VI

By: Graham Iddon

The Adventure of Exhibit Planning V

By: Graham Iddon

The Senior Deputy Governor’s Signature

By: Graham Iddon

Becoming a Collector V

By: Graham Iddon

Becoming a Collector IV

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction - Part 3

By: Graham Iddon