A First World War souvenir coin tells its stories

It is 1919, and a Canadian soldier awaits his discharge from the army. With time to reflect on the most traumatic events he will ever experience, he creates a personal memorial.

Trench art

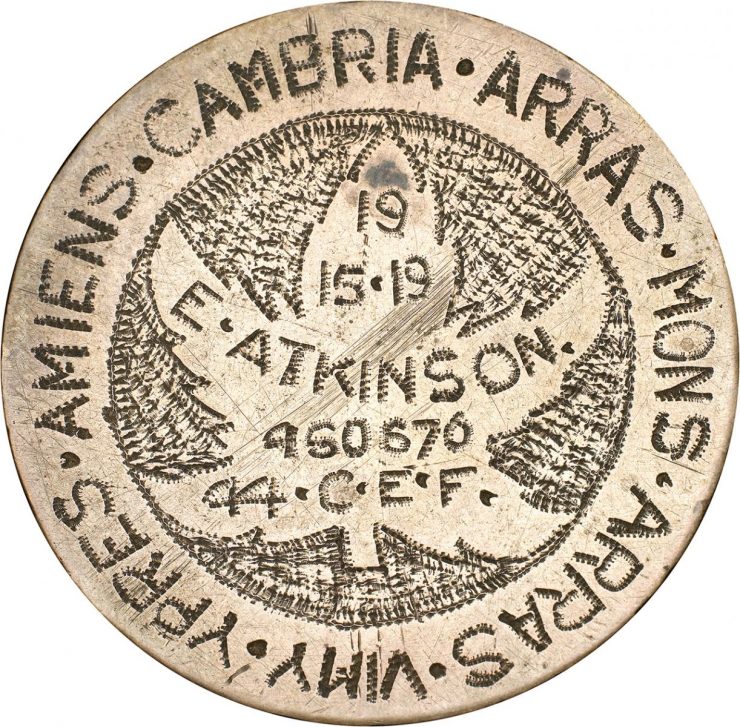

Creating trench art was a common pastime for First World War soldiers. Scrap metal, wood and especially brass shell casings were a popular medium to make ash trays, cutlery, lamps and jewelry with—most carefully inscribed with dates, regiments and places. Such things became mementos of often unimaginable experiences. Private Edward Atkinson’s example of trench art is what is called a “love token”—a souvenir made from a coin. It’s one man’s personal wartime experience expressed through a pocket-sized medium.

Discovering a soldier’s story

The love token itself tells us a fair amount: the battles he took part in, his name, his rank, his battalion and his regimental number. This is a great starting point for a much deeper dive into the Great War history of Private Atkinson.

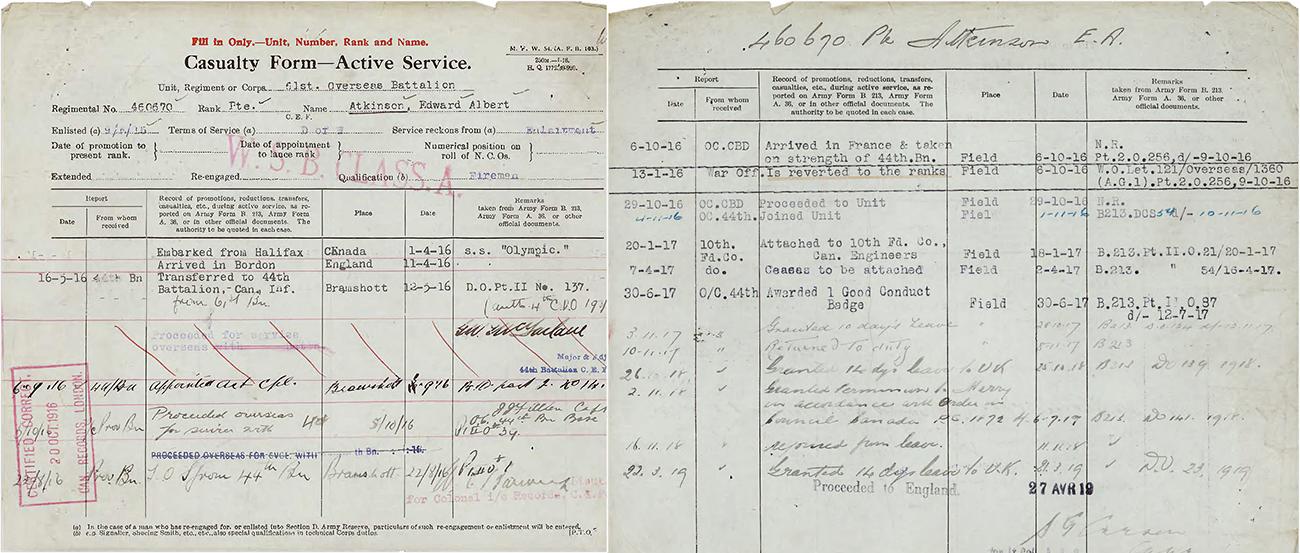

Atkinson’s army service records can be found at Library and Archives Canada. At times vague, illegible and conflicting, the contents reveal much about his recruitment, health, family and movements. His actual battle experience is only suggested in these documents. But battalion records and the general history of Canada in the Great War help us read between the lines. Follow us down Atkinson’s trail.

Casualty forms and Active Service records outline much of Atkinson’s war service. But they show only his comings and goings from the battlefield. Conclusions can still be drawn from this material, however.

Library and Archives Canada, 1992-93/166, item 16237

Who was Edward Atkinson?

Edward Albert Atkinson was born on January 22, 1888, in Beddington, Surrey, England (a neighbourhood of Croydon, part of greater London). Atkinson emigrated to Canada in 1906, settling in Winnipeg, where he was a construction worker and firefighter.

Canada went to war in support of England only eight years later. Edward Atkinson answered the call for king and country and enlisted in the 61st Battalion, Winnipeg Light Infantry, in June 1915. At 27, he was considered a little old for it, but still fit for service. The 61st trained at Camp Hughes near Brandon, Manitoba.

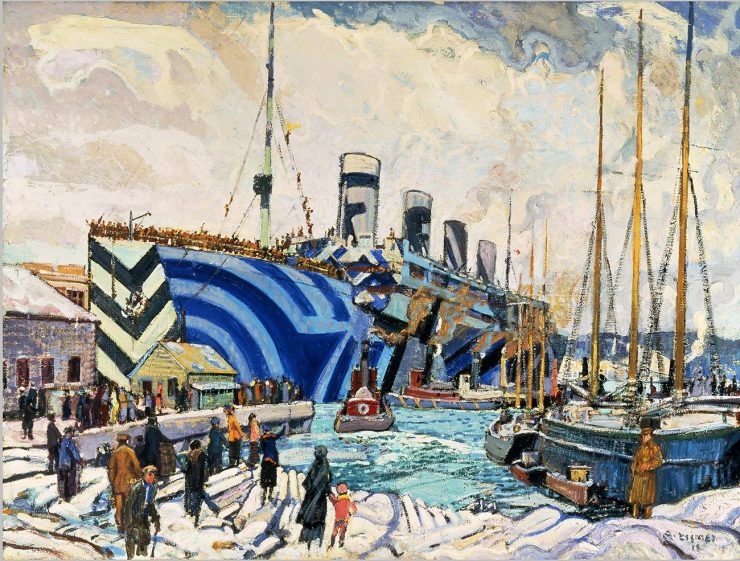

On April 1, 1916, Atkinson (and over 5,000 other troops) departed for England from Halifax Harbour aboard the HMT Olympic. (His Majesty’s Troopship)

Atkinson goes home to go to war

Once in England, Atkinson was transferred to the 44th Battalion. More training took place at Bramshott, Hampshire, where the Canadian Expeditionary Force prepared for the trenches. Sometime that May, Private Atkinson went on leave in London. There, he contracted an infection from “intemperance and improper conduct,” according to his official medical history. Atkinson spent the following few weeks in Connaught Hospital in Bramshott. It was the only recorded medical attention he would need during his three years on the Western Front. On October 5, 1916, he shipped out to France to join his unit.

Officers of the 44th Battalion, Canadian Infantry, are photographed after the war ended—probably still in France. Private Atkinson likely served under a number of these men.

Cdn. Dept of Nat’l Defence, Library and Archives Canada, 1964-114 NPC

Private Atkinson’s battles

Arras and Vimy

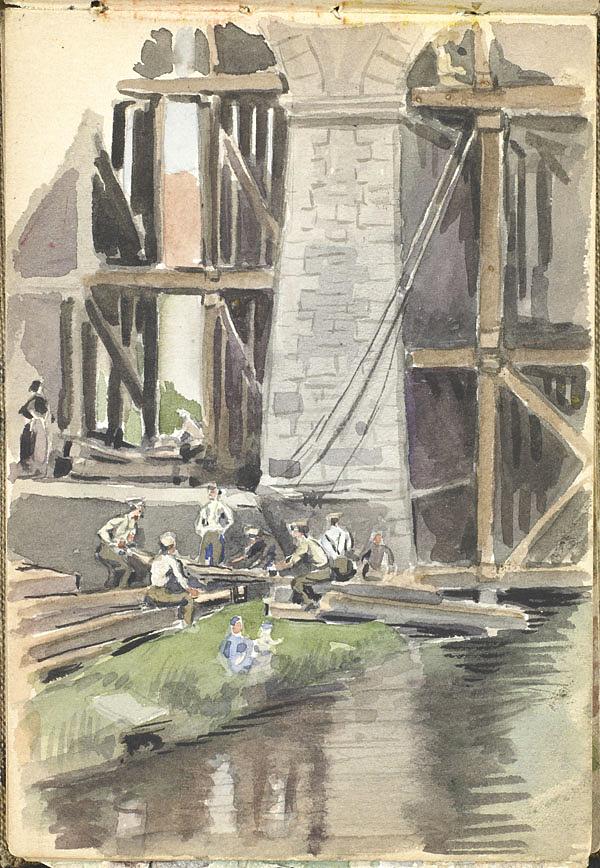

Army engineers built or repaired infrastructure, as these men are doing on a bridge near Calais, France. The artist was William Redver Stark of the 1st Battalion of Canadian Railway Troops. Library and Archives Canada, e008315355

The following January, Atkinson was attached to the 10th Field Company, Canadian Engineers. This was a company of bridge builders and tunnellers. He joined them in time for preparations for the Arras campaign, which included the Battle of Vimy Ridge. For the engineers, this would mean building kilometres of tunnels and roads, laying railway tracks and stringing communication lines. Atkinson worked with this unit until called back to the 44th Battalion less than a week before the great Battle of Vimy Ridge began on April 12. Since he had not trained for the actual attack, we don’t know what his role was in this extraordinary Canadian venture, but his coin tells us he was there.

Ypres or Passchendaele

Next on Private Atkinson’s coin is Ypres. Three important battles have been named for this medieval Belgian town. The third of these battles, beginning in October 1917, is better known as Passchendaele. It was one of the war’s costliest battles, killing or wounding almost half a million soldiers from both sides combined. Our soldiers were again asked to do what was considered nearly impossible—to capture Passchendaele Ridge itself. They did so in late November, and it is considered Canada’s second Vimy. According to records, Atkinson joined the fight there that same month.

Passchendaele: “Dante would have given it an honourable place in his collection of hells.”

Ralf Frederic Lardy Sheldon-Williams, author of The Canadian Front in France, 1920

Library and Archjves Canada, PA-002167

The history of the 44th Battalion history records no battles until the following summer. There is a matching gap in both Atkinson’s records and his coin at this point. We can learn nothing of him but for the next battle inscribed on the coin: Amiens.

Amiens, Cambrai, Arras, Mons

In April 1918, the German army executed a huge offensive that drove deep into Allied territory. An Allied counter-attack, later called the Hundred Days Offensive, began with the Battle of Amiens in August and would end in Mons, Belgium on November 11, 1918.

The Allies (now including American troops) pushed an exhausted and poorly supplied German army back across the wastelands that were the battlefields of the previous four years. This second appearance of Arras on Atkinson’s coin likely indicates his battalion’s participation in the capture of the Canal du Nord, but we can’t be certain. Near the town of Cambrai, Canadians built a bridge to funnel troops across the canal, which may account for Cambrai showing up on the coin at this point.

The ruins of Arras, France, in 1919. Private Atkinson passed this way less than a year earlier.

Fred Schultz, Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs 165-PP-15-19

Cambrai’s appearance on the coin is a bit perplexing. For Atkinson, however, this is how he personally identified this battle, long before official histories arose—like Ypres for Passchendaele. As historians would later do, Atkinson noted his next battle as “Mons.” He and his remaining colleagues marched into the south-central Belgian town on November 11, 1918—that morning, Germany surrendered. Less than a week later, Edward Atkinson took leave, made his way to England and got married to a woman named Dorothy.

“Canadians marching through the streets of Mons, morning of November 11, 1918.”

Library and Archives Canada, 1964-114 NPC, item 0-3657

After the war

We do not know Mrs. Dorothy Atkinson’s maiden name. From Edward’s pay records, we do know that she lived in Croydon, near where he grew up. Perhaps they knew each other as children; maybe he met her on leave. All we know for certain is that, following the Armistice, they married, and soon after, Atkinson returned to France.

In April 1919, he was still in France. The process of sending home nearly a quarter of a million Canadian soldiers was long, frustrating and tedious. Atkinson wasn’t officially discharged until August 22, 1919. It was probably during the spring and summer of 1919 that he made an Italian coin into a personal memento of his war.

On August 8, 1919, Dorothy Atkinson boarded the SS Corsican, a Canadian Pacific steamship, in Liverpool, England. She disembarked in Québec City ten days later. She and Edward were likely on the same ship, but Edward was obliged to stay with the Clearing Services Command Depot in Québec City for nearly two weeks—the last stages of his eight-month-long demobilization process. They then moved to Manitoba and Edward’s Canadian home town.

According to Canada’s 1921 census, Edward and Dorothy lived at 644 Higgins Avenue, now a commercial street of construction companies and industrial firms near Winnipeg’s old downtown. Edward was listed as working in a dairy. The Atkinsons do not appear in the 1926 Prairie Province census.

The Atkinson trail ends here. If any of Dorothy and Edward Atkinson’s relatives have any more insight into their lives before, during or after the First World War, please feel free to contact us at our general e-mail address.

The Museum Blog

Notes from the Collection: Moving Forward

By: Raewyn Passmore

Notes from the Collection: A Buying Trip to Toronto

By: Paul S. Berry

Director’s chair : A little help from our friends

By: Ken Ross

The Cases are Almost Empty

By: Graham Iddon

Curators Begin Removal of Artifacts

By: Graham Iddon

Notes from the Collection : 2013 RCNA Convention Winnipeg

By: David Bergeron