How a subway token halted plans to change the Canadian penny

In 1977, the Royal Canadian Mint wanted to reduce the size of the penny in response to the rising price of copper. Little did the Mint know that the Toronto Transit Commission’s reaction would force the cancellation of the program.

Tokens of my youth

Going to high school in Toronto in the late 1980s, my classmates and I would sometimes skip our afternoon classes and ride the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) to catch a Blue Jays game, hang out at the Eaton Centre or bug the vendors in Kensington Market. (Of course, I don’t advocate skipping school anymore!)

Back then, riding the subway cost about 80 cents. TTC tokens were aluminum, smaller than a dime and easy to lose. Occasionally, my mom would find a token in the lint trap of the clothes dryer. I did not take transit to school, so she was on to me—I was busted for skipping class! Scraping up enough money to pay a fare meant that it was important to guard these tokens—the more so to avoid my parents’ discovering my antics.

But this story is not about the joys of skipping school and exploring the big city. Instead, it’s about the tokens I used when I rode the subway. And, more precisely, about how in 1978 these little tokens forced the Royal Canadian Mint to cancel its plan to issue a new, smaller Canadian cent.

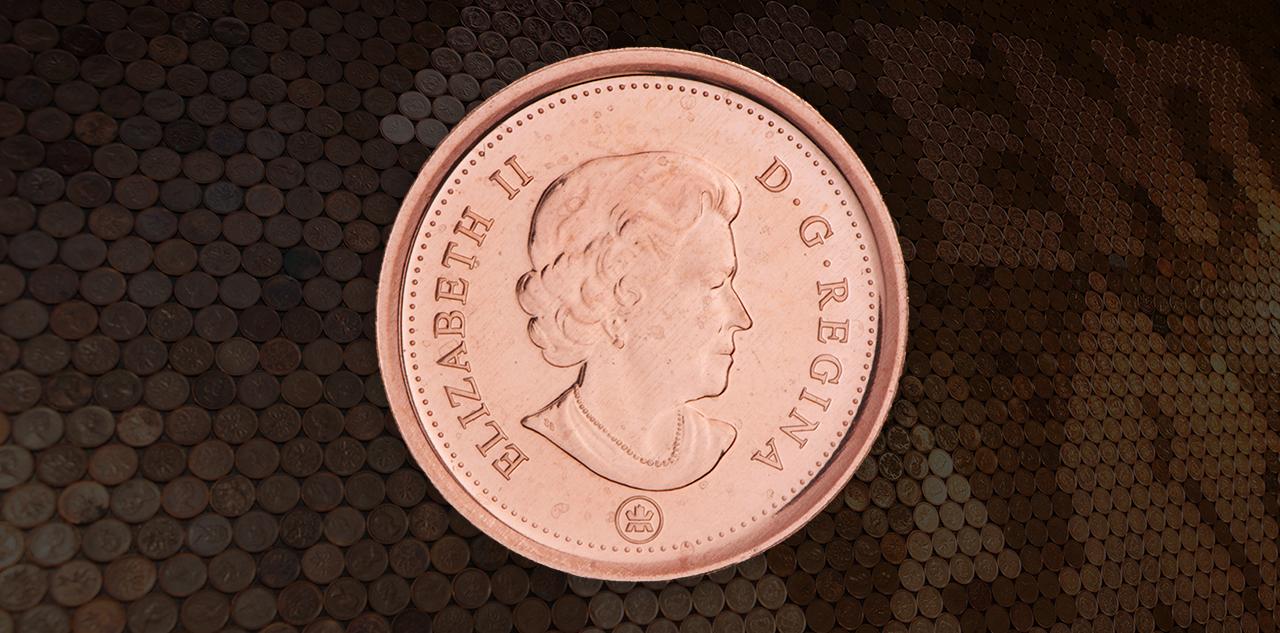

TTC tokens from 1975 to 2007 were made of aluminum, after which they were bi-metallic to reduce counterfeiting.

1 fare, Toronto Transit Commission, Canada, 1975 (front and back)

The cost of a penny

A typical cent from 1977, which actually cost two cents to make. One cent, Canada, 1977

After the Second World War and the post-war boom, demand for Canadian coins was on the rise. From the mid-1950s, the production of Canadian cents grew from tens of millions to hundreds of millions. In 1976 alone, the Royal Canadian Mint produced nearly 700 million pure-copper pennies.

Along with the increased demand for coins, the price of copper was also on the rise. Through the 1970s, copper prices rose from an average 60 cents per ton and peaked at $1.36 per ton in 1980. In 1977 the Master of the Mint, Yvon Gariépy, reported that it cost two cents to mint a penny. Something had to be done to reduce costs, and the solution was to reduce the size of the coin.

New laws and a smaller cent

In 1977, the Mint proposed to the Minister of Finance a reduction in the size of the penny from 19 mm to 16 mm, requiring an amendment to the Currency Act (the law governing currency design and production).

Along with the reduced size, a new design was planned to replace George Kruger Gray’s iconic 1937 depiction of two maple leaves. The new design was consistent with the simple, modern look of coins the Mint was producing for other countries at the time. By summer 1977, master dies for the new coin were ready, and minting of the new coins was underway.

Riding the TTC for a penny?

In the next few months, word of the new cent reached the TTC. The proposed coin was about the same size as a TTC token, 16 mm, and it had the Toronto Transit Commission worried. Instead of TTC tokens, people might be able to use the penny in the subways’ automatic turnstiles. Enough pushback from the TTC, and other companies using similar tokens, forced the Royal Canadian Mint to cancel its plan to issue the new coin on January 1, 1978.

A byline from The Globe and Mail, December 24, 1977.

Back to the drawing board

The Mint continued to strike pure-copper pennies at a loss, producing nearly a billion coins to make up for the loss of the previous year’s production. In 1980, the Mint came up with a cost-saving solution to keep the size of the cent at 19 mm: reduce its thickness.

As the cost of copper continued to rise, the Mint resorted to producing plated coins in 2000. The new penny had a steel or zinc core and was plated with a thin layer of copper to give it the appearance of a regular copper cent. But each coin still cost more to make than it was worth. The penny had reached the end of its life. In 2012, the demise of the penny was formalized in a ceremony at the Mint’s facility in Winnipeg, where then Finance Minister Jim Flaherty struck the last Canadian one-cent piece. That coin is currently on display in the Bank of Canada Museum.

Canada’s very last penny, minted by Jim Flaherty on May 4, 2012. One cent, Canada, 2012

TTC tokens have been around since 1954, when Toronto’s first subway line went into operation. It’s ironic, in a way, that the TTC token outlasted the Canadian penny. Yet with changes in payment technology and the increased cost of commodities and production, TTC tokens, bus tickets and transit passes are being phased out this year in favour of the Metrolinx Presto card. I wonder if TTC riders will be sad to see their little tokens disappear after 65 years.

More than 50 years of TTC tokens from aluminum to brass to bi-metallic. Three tokens, one fare, Toronto Transit Commission, Canada

References

- James Bow, 2017, A History of Fares on the TTC, accessed February 8, 2019,

https://transit.toronto.on.ca/spare/0021.shtml - The Globe and Mail, December 24, 1977.

- Mactrotrends.ca, 2019, Copper Prices—45-Year Historical Chart, accessed February 8, 2019,

https://www.macrotrends.net/1476/copper-prices-historical-chart-data. - M. Drake, 2018, A Charlton Standard Catalogue of Canadian Coins: Vol. 1 Numismatic Issues, 71st edition, Toronto: Charlton Press.

The Museum Blog

The Hunting of the Greenback

By: Graham Iddon

What goes up…

By: Graham Iddon

Welding with Liquid

By: Stephanie Shank

Conserving the Spider Press

By: Stephanie Shank

How Does $ = Dollar?

By: Graham Iddon

The Vertical Note That Almost Was

By: Graham Iddon