From one medium to another

The release of the two-dollar coin and a bit of dark trivia about Canada’s two-dollar bill.

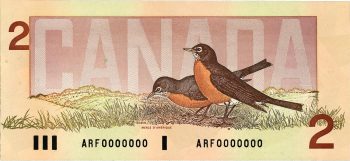

The very last two-dollar notes ever printed, and the toonie that replaced them.

A note with a reputation?

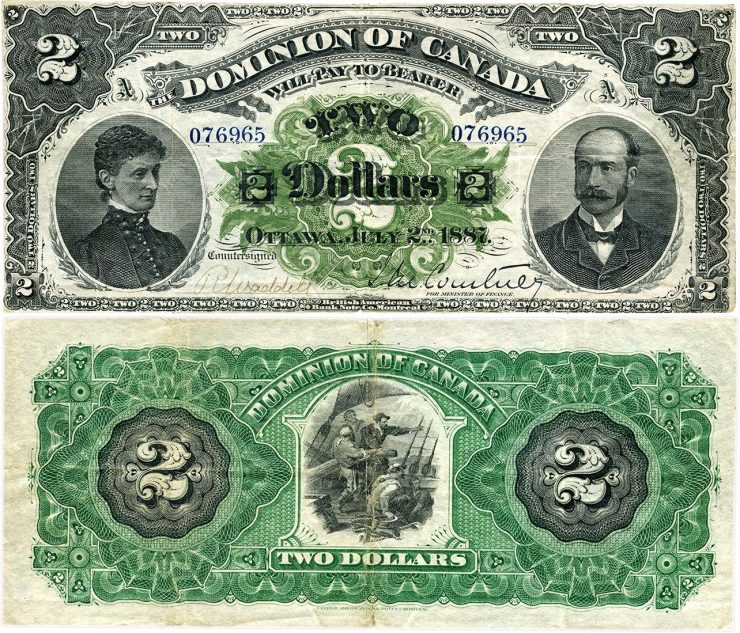

This note would have been in circulation soon after the Canadian Pacific Railroad opened the West up to mass settlement. The portraits are of the Governor General and his wife, the Marquis and Marchioness of Lansdown. 2 dollars, Dominion of Canada, 1887. NCC 1964.88.875

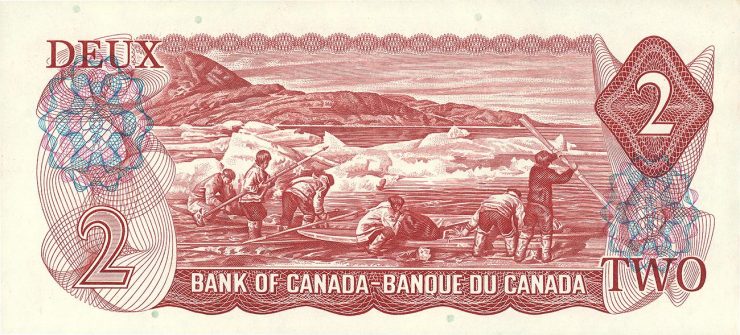

The Canadian two-dollar note had been around since before Confederation. But to a Western Canadian, a two-dollar bill was a relatively unfamiliar thing. As the story goes, this note became associated with the shadier dealings of the frontier era—specifically prostitution. Though this association is purely hearsay, the two-dollar bill was never popular out west.

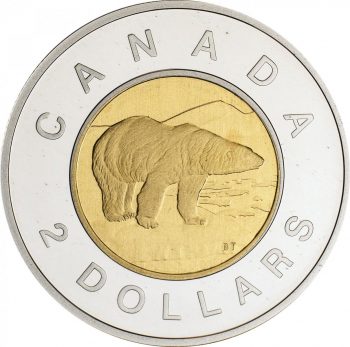

Gifted nature artist Brent Townsend created the polar bear that has been on our toonie since 1996. 2 dollars, Canada, 1996, NCC 1996.31.40.1

In 1996, the paper note was replaced by a coin. Of course, that decision had nothing to do with any sordid associations Westerners might have had for these innocent notes. It was an economic decision—a cost-saving measure.

Paper bills simply don’t hold up to daily wear and tear nearly as well as coins do. The life expectancy of a two-dollar note was about a year. But coins can last more than 10 years. Even a polymer bank note, such as those Canada now produces, can’t match that sort of longevity. Although minting a coin costs far more than printing a note, the coin option is definitely more affordable when you consider the cost of printing 10 notes for every coin. And the history of the toonie bears that out.

Note designers hoped this simple design would make any flaws on notes counterfeited using colour copiers obvious. 2 dollars, Canada, 1986, NCC 1986.42.3

Bank notes and parking meters don’t mix

Although some Canadians were happy to see the old two-dollar notes disappear, the new coin initially met with some resistance. There were even rumours that the centre sections might fall out. These reports proved untrue and Canadians soon adapted to the new coin. After all, it is convenient for vending machines and parking meters.

In fact, the new coin ended up being so well received that the Royal Canadian Mint had to ramp up production. Some 325 million two-dollar coins were struck in the first year alone. If you periodically check your change, it’s very possible you’ll still find toonies from the first minting of 1996. Since then, annual production has varied between 10 and 30 million.

A coin becomes a toonie

As its popularity grew, Canadians gave the two-dollar coin its affectionate nickname. For those of you unfamiliar with why, here’s a quick bit of social history. The Canadian one-dollar coin, featuring an illustration of a loon, quickly picked up the name “loonie.” Instead of some sort of polar bear reference, the new coin became known as a “toonie,” as in two loonies. In fact, the “bearie” was put forward, but a nickname has a life of its own and “toonie” appears to be here to stay.

In 2006, the Mint opened a competition to name the bear on the toonie. Churchill was the winning name—a reference to the Manitoba town famous for polar bear watching. The runners up were Wilbert and Plouf.

The Museum Blog

How Does $ = Dollar?

By: Graham Iddon

TTC Tokens and the Proposed 1978 Cent

By: David Bergeron

The Vertical Note That Almost Was

By: Graham Iddon

The Canadian Roots of the “Greenback”

By: Graham Iddon

What’s Up Next for 2019?

By: Graham Iddon

Boer War Siege Money

By: Graham Iddon

The first Canadian nickel

By: David Bergeron

A Good Deal

By: David Bergeron

Esperanto: universal language¬—universal coinage?

By: David Bergeron

Tea brick Currency

By: Raewyn Passmore