It’s all there in green and white

The roots of the name “greenback” reach back to the American Civil War. A little-known fact is that the anti-counterfeiting ink that inspired the nickname was invented in Canada.

What’s in a name?

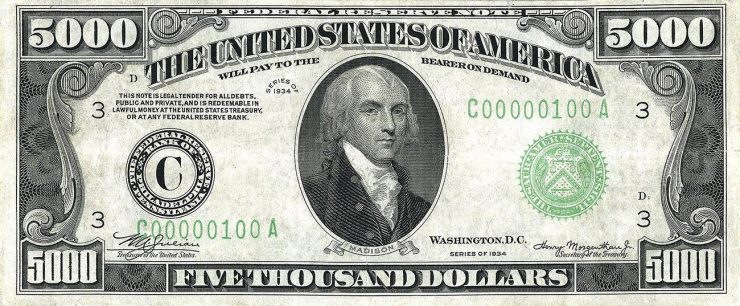

In Raymond Chandler’s 1953 novel The Long Goodbye, private detective Philip Marlowe receives a letter with “…a portrait of Madison in it.” Huh? Marlowe is referring to the $5,000 bill featuring an engraving of former US President James Madison.

This note would have been used by banks but not the public. In today’s money, it would be worth over US$90,000. Image: Wikimedia commons

The American vernacular of Chandler’s day was full of nicknames for paper currency, such as “folding money,” “c-notes,” “centuries,” “sawbucks,” “bills,” “Benjamins,” “Jacksons” or “Lincolns.” The most enduring of these terms is “greenbacks.” The roots of that name reach back to the American Civil War, when the US government issued notes that carried a large, complex, green geometric pattern on the back—hence, “greenback.” A little-known fact is that the anti-counterfeiting ink that inspired the nickname was invented in Canada.

A photo opportunity for a counterfeiter

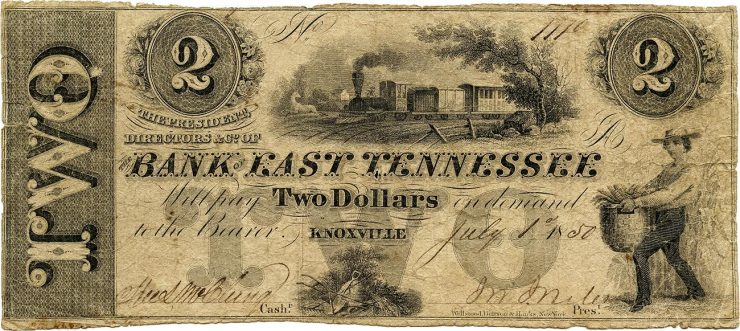

Bank notes of the early to mid-19th century were generally printed with black ink. Successfully counterfeiting a bank note in those days required an engraver with reasonably high talent and very low ethics.

This note was typical of the pre-Civil War era. It was one-sided and printed with black ink. 2 dollars, Bank of East Tennessee, USA, 1850, NCC 1979.175.54

But the invention of photographic printing changed that—at least the bit about talent. With a camera, counterfeiters could quite easily reproduce a convincing bank note without the effort of engraving printing plates.

Recently several attempts to counterfeit bank notes by means of photography have been successful; and this fraud has not been confined to bank notes—other valuable documents having been copied in a similar manner.

The Photographic News, October 22, 1858

Security printers responded by adding coloured inks to their notes. Counterfeiters then removed the coloured ink, photographed the remaining black portions and used a secondary process to reprint the coloured areas. The security printers’ next move was to look for a coloured ink that was difficult, if not impossible, to remove from a legitimate bank note. And that sought-after ink came from Canada.

Thomas Sterry Hunt was an American, but he created his security ink in a Canadian lab. Image: Wikimedia, c. mid-19th century

Canadian content

Dr. Thomas Sterry Hunt invented the ink while teaching at Laval University in Québec in 1857. It was developed in response to an appeal by the President of the Montreal City Bank, whose notes were being counterfeited. Called “Canada Bank Note Tint,” the ink was an “anhydrous sesquioxide of chromium.” For those of us without a PhD in chemistry, this means that chromium was super-heated in a near oxygen-free environment, where it would decompose. The resulting material was then mixed with linseed oil to make ink in a green shade similar to oxidized copper. This ink turned out to be extremely resistant to almost any attempt to chemically or physically remove it from paper. Because Hunt wasn’t a British subject, he wasn’t allowed to patent the ink. George Matthews, a chemist with the Montreal City Bank, filed the patent on Hunt’s behalf and forwarded him the royalties.

The Ontario Bank was founded in Bowmanville, Ontario in 1857. This is among the earliest Canadian notes to use the “Canada Bank Note Tint.” 1 dollar, Ontario Bank, Upper Canada, 1857, NCC 1963.43.1

An indestructible ink?

An anti-counterfeiting organization had the ink tested by a number of well-known chemists. John Torrey, a Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, certified that, “The green compound is insoluble and indestructible by all chemical agents, except such as will destroy the paper itself.” Chemist Wolcott Gibbs of the Free Academy of New York discovered that the ink could be removed by boiling the note in concentrated oil of vitriol—better known as sulphuric acid. Finally, chemist Charles T. Carney discovered a way to remove the green ink while leaving the rest of the note untouched.

So, in August 1857, the Executive Committee of the Association of Banks for the Suppression of Counterfeiting voted, unanimously, that the Executive Committee cannot recommend to the associated banks the Patent Green Ink.

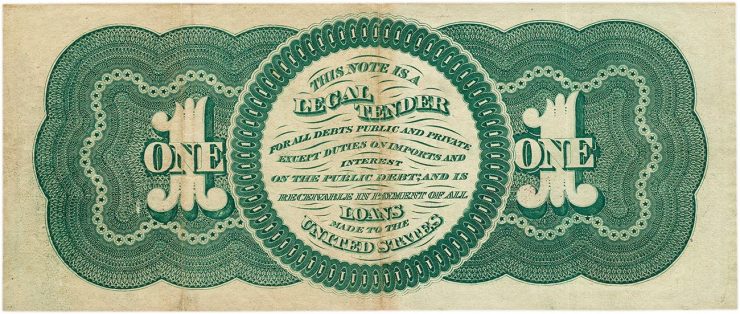

Still, US bank note printers were sufficiently impressed with the ink to use it on the US government’s Civil War bank notes—most notably on the back.

The birth of the greenback

These notes, soon christened as “greenbacks,” were created to help fund the Union effort in the American Civil War. Like today’s bank notes, greenbacks were fiat money and not exchangeable for gold at a bank. They were, however, legal tender that could be used to buy everyday goods, pay debts or taxes and buy government bonds. During the war, greenbacks displaced most of the state-bank notes, which had dominated the economy until then. And “greenback” proved to be a sticky name, eventually referring to any American bank note.

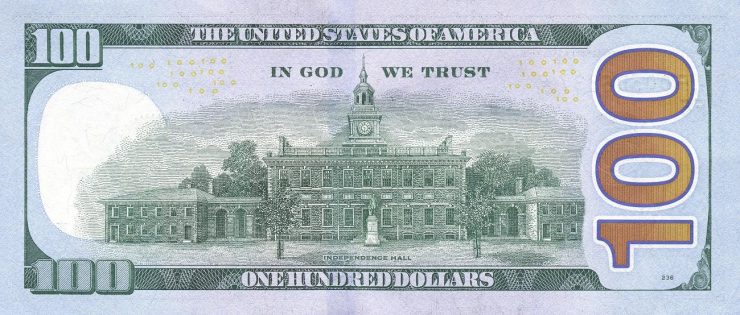

Ever since then, the back of most US government bank notes has been printed in green. Even on today’s more colourful series, the vignettes on the back of US bank notes are still that familiar colour of long tradition. They’re just not printed with “Canada Bank Note Tint.”

It’s hard to say whether American money would look like this if it hadn’t been for a nickname given to a series of Civil War notes. 100 dollars, United States, 2009, NCC 2016.58.1

So, the next time you are in the United States and pull out a greenback, take a look at the illustration of the great American icon on the back and remember that, in spirit at least, you’re looking at a tiny bit of Canada.

The Museum Blog

The Scenes of Canada series $100 bill

By: Graham Iddon

Caring for your bank notes

By: Graham Iddon

Teaching math using money

By: Jonathan Jerome

Caring for your coins

By: Graham Iddon

Security is in the bank note

By: Graham Iddon

Teaching art with currency

By: Adam Young

New Acquisitions—2022 Edition

Money: it’s a question of trust

By: Graham Iddon

The day Winnipeg was invaded

By: David Bergeron

Positive notes

By: Krista Broeckx