Or Col. Baden-Powell does his best

Colonel Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell was a British Army officer who commanded troops stationed in the South African town of Mafeking (now Mahinkeng) during the Second Boer War, also known as the South African War. From October 1899 to May 1900, the town was surrounded by a force of Boer (Dutch South African) fighters. Soldiers, men, women and children would endure a 217-day siege with food rationing and regular risks to life and limb. Under martial law, the 5,500 Mafeking civilians were kept to a strict, semi-military agenda—no one was exempt. Even the children played a role, the boys carrying messages between officers in the town. The conditions were harsh and Mafeking was bombarded daily—except on Sundays. The Boers were strict observers of the Sabbath.

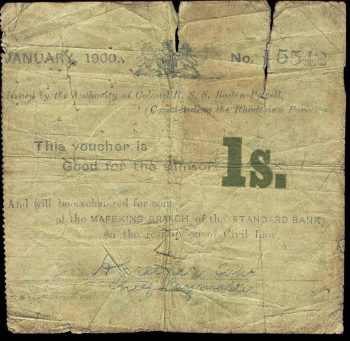

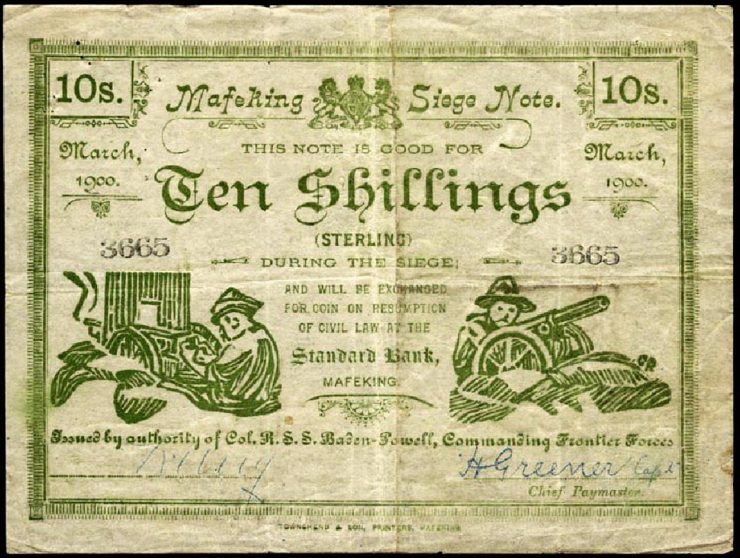

As in any siege, Mafeking quickly began to run short of most things, not the least of which was currency. People generally hang onto their coins during sieges (called hoarding). With so little cash in circulation, Baden-Powell had resorted to issuing emergency paper money in the new year. The notes were even legally supported. The local army paymaster, Captain H. Greener, wrote £5,228 in cheques to the Standard Bank of South Africa, backing every issue of notes. Once there was a return to civil law, this siege money could then be exchanged for cash at the Standard Bank, where funds would already be in place.

Five denominations of notes were printed by Townsend & Son in an underground space nicknamed “the Mafeking Mint.” The one-, two- and three-shilling notes were simply coupons for use in canteens that distributed rations of rough oat bread and horse meat.

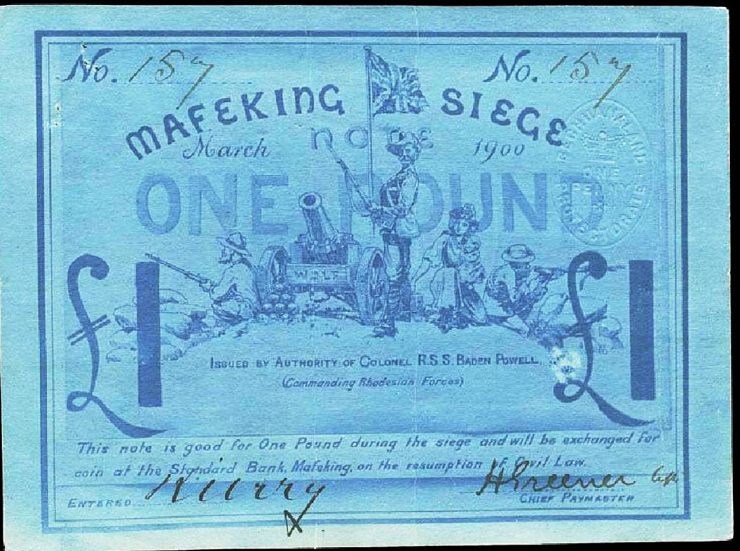

Baden-Powell took a personal interest in the 10-shilling and one-pound notes. He drew the design of the one-pound note onto the head of a croquet mallet. A craftsman then carved the design into the wood. Dissatisfied with the results, Baden-Powell used the croquet mallet woodcut to print the 10-shilling notes and drew a far more detailed (and amazingly competent) image that was photographically reproduced for the one-pound notes.

The Baden-Powell drawing on this note shows the cannon “Wolf” that soldiers built from an old steel pipe. 1-pound siege note, Mafeking, South Africa, 1900

The notes successfully circulated throughout the siege. But, afterward, a curious thing happened: almost nobody cashed them in. Edward Ross, Mafeking’s auctioneer, predicted, “I am sure they will be worth much more than face value as curios after the siege…” And so they were. Only a mere £638 worth were ever redeemed at the Standard Bank, leaving a whopping £4,590 on credit. In today’s money, that is nearly $800,000. This expensive loose end would dog Baden-Powell until it became an issue in the House of Commons. The Standard Bank eventually repaid the money to the army paymaster in 1910.

The upstanding and ever-resourceful Baden-Powell was praised for his imaginative tactics in holding off the enemy during the siege. Under his command, the people of Mafeking survived with only modest casualties until British soldiers arrived in the spring of 1900 to drive out the Boers. At home, Baden-Powell became a national hero for his actions, romanticized by an adoring press. However, it has since been debated whether he needed to hold out for so long or whether his defiant stand was even necessary. Military authorities of the day were not pleased that he had made no attempt to break out of Mafeking. Though he was a gifted and inspired leader, attack did not appear to be Baden-Powell’s forte. In a later battle, he again allowed himself to be besieged and the army quietly withdrew him from active service.

While in Africa, Baden-Powell wrote a training book on military reconnaissance and scouting (Aids to Scouting) that became a bestseller in Britain. In 1908 he wrote a similar book called Scouting for Boys that was said to be inspired by the role young boys played in the siege. In England, he organized big camping adventures to test his ideas of applying military scouting and woodcraft practices to youth training—and the Boy Scouts was born. Nearly simultaneously, Baden-Powell, his wife and his sister also launched the Girl Scouts. Baden-Powell’s theories of “good citizenship through woodcraft” spread around the world. The various editions of his book sold more than 100 million copies worldwide. And Baden-Powell became a legend.

Boy Scouts from Newfoundland visit their new national seat of government during an Ottawa jamboree in 1949. A. Beaver, Library and Archives Canada, e010948819

The Museum Blog

Paul Berry is Retiring? Say it Ain’t So!

Money of the First World War

By: Paul S. Berry

Money’s Magnificent Moustaches

By: Graham Iddon

The Devil is in the Hairdo

By: Graham Iddon

Canada Financially Comes of Age

By: Paul S. Berry

#AskACurator Day 2018

By: Graham Iddon

Happy Birthday, Dear Bank of Canada Museum!

By: Graham Iddon

Sculptor Dora de Pédery-Hunt

Operation Fish

By: Robert Low

New Acquisitions

By: Paul S. Berry