Tea brick currency

Tee, thé, cha, tsài, tè, teo, chai, teh, chay—these are all words for the beverage made from leaves of the evergreen shrub Camelia sinensis. Wars have been fought to control its trade and gifts of it have been made to ensure peace. It has even been used as currency. In central and northern Asia, bricks of tea were a unit of value and medium of exchange well into the 20th century.

China had a monopoly on the tea trade right up until the 19th century and, as the taste for tea spread, it became an increasingly valuable commodity. It was exchanged for horses in Mongolia and Tibet. Russian caravans travelled for months across Siberia to trade furs for it.

Tea in the form of bricks was durable, easy to pack and, under the right conditions, could be preserved indefinitely. At factories in China’s Sichuan Province, freshly picked leaves were steamed, pounded into powder and then packed into moulds. The bricks were then dried or baked in the sun to harden.

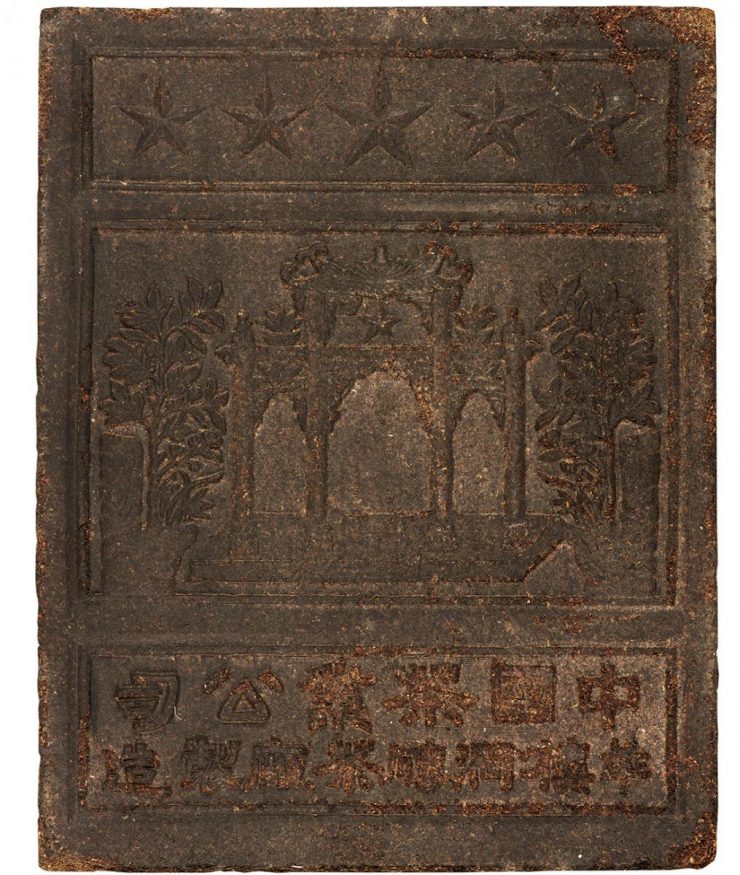

The characters tell us that the brick was made by the China Tea Industrial Corporation at the Zhao-Li-Qiao Tea Brick Factory in Hubei Province. Tea brick, China, mid 20th century

The value of a brick depended on both the quality of the tea and the distance it had travelled from China. A French missionary travelling in Tibet in the 19th century wrote, “men bargain by stipulating so many bricks or packets (4 bricks) of tea.” Workmen and servants were paid in bricks of tea and a horse cost 20 packets. At the beginning of the 20th century, Western adventurers in remote parts of Mongolia and Tibet found that they couldn’t use gold or silver to buy supplies, but could only use tea.

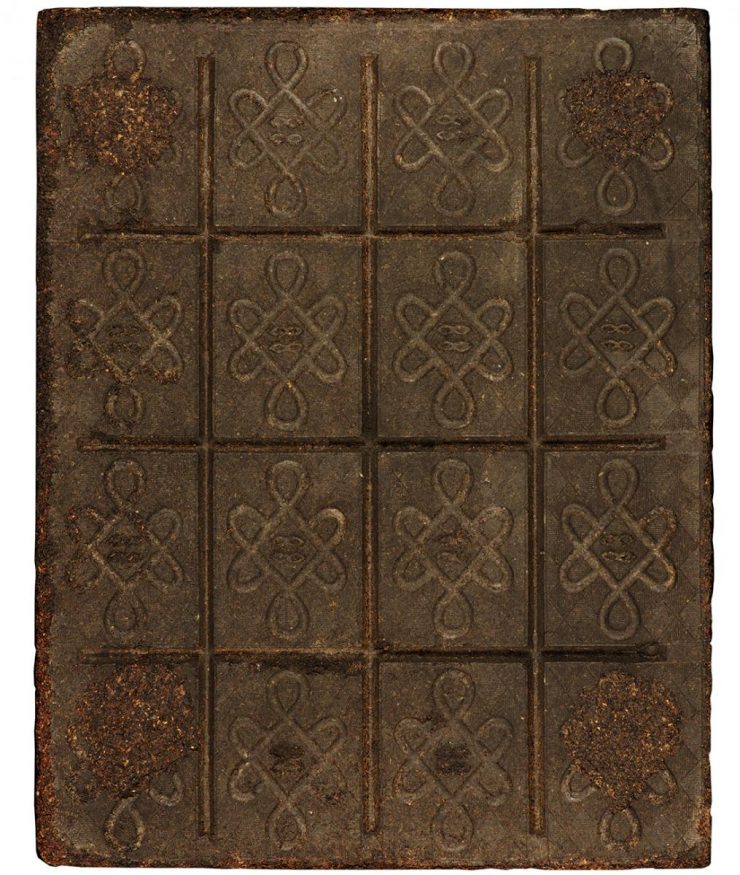

A very practical money, each tea brick was scored so that sections could be broken off for change, small purchases, or a quick pot of tea. Tea brick, China, mid 20th century

The tea brick shown here was produced in the People’s Republic of China sometime in the mid-20th century. It is in the Bank of Canada Museum’s National Currency Collection and can be seen in Zone 4 of our main gallery along with many curious and fascinating objects that have been used as money.

The Museum Blog

The Hunting of the Greenback

By: Graham Iddon

During World War Two, the Bank created the Foreign Exchange Control Board (FECB). One of its major tasks was to find as many US dollars as possible to pay for American imports.

What goes up…

By: Graham Iddon

Economic bubbles continued to pop up regularly throughout history, and still do today.

Welding with Liquid

By: Stephanie Shank

In heritage conservation, broken metal objects can be reassembled with an adhesive most commonly used for repairing glass and ceramics.

Conserving the Spider Press

By: Stephanie Shank

Used extensively in the 19th century, this type of hand-operated press printed secure financial documents using the intaglio method.

How Does $ = Dollar?

By: Graham Iddon

How on earth did an “S” with a line or two through it come to represent a dollar? Any ideas? No? That’s OK, you’re in good company.

TTC Tokens and the Proposed 1978 Cent

By: David Bergeron

In 1977, the Royal Canadian Mint wanted to reduce the size of the penny in response to the rising price of copper. Little did the Mint know that the Toronto Transit Commission’s reaction would force the cancellation of the program.

The Vertical Note That Almost Was

By: Graham Iddon

The printing firms’ design teams went to work and came back with a surprising result: vertical notes.

The Coming of the Toonie

The life expectancy of a two-dollar paper note was about a year. But coins can last for more than 10 years.

The Canadian Roots of the “Greenback”

By: Graham Iddon

Successfully counterfeiting a bank note in the mid-19th century required an engraver with reasonably high talent and very low ethics.