Playing cards as money

You’ve probably heard of sea shells being used as money, or perhaps elephant hair, cigarettes or nails. In Canada, playing cards were used as form of emergency money at a time when the colony constantly suffered from a shortage of hard currency—that is, gold and silver coins.

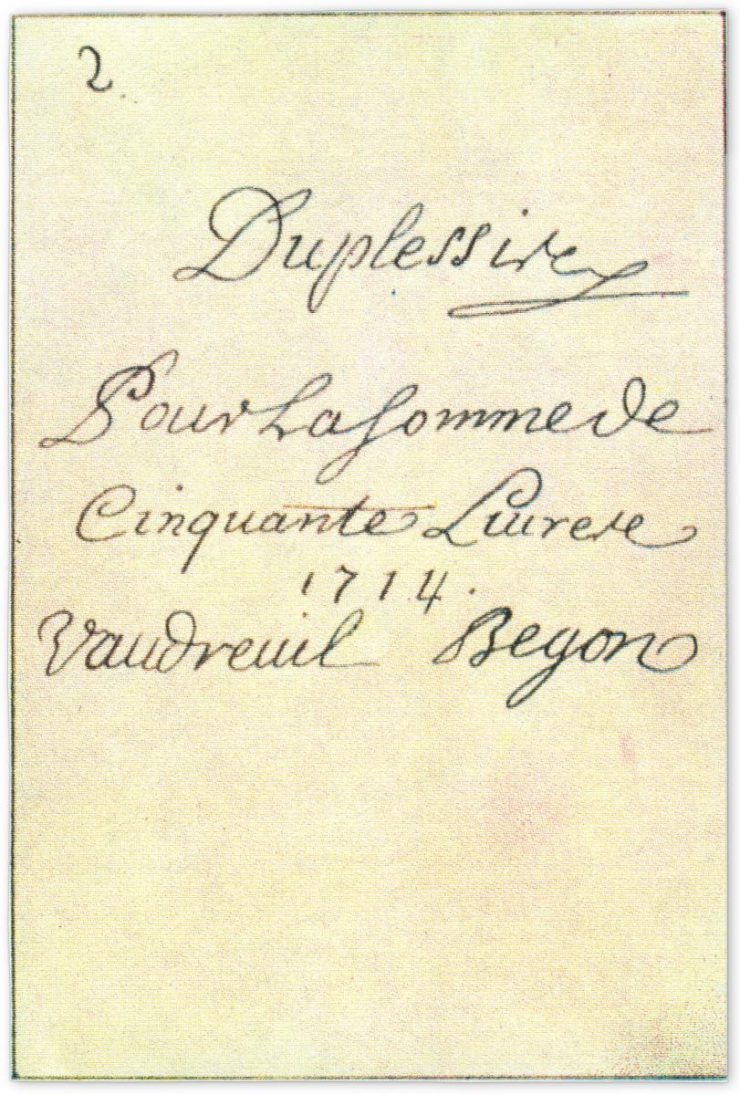

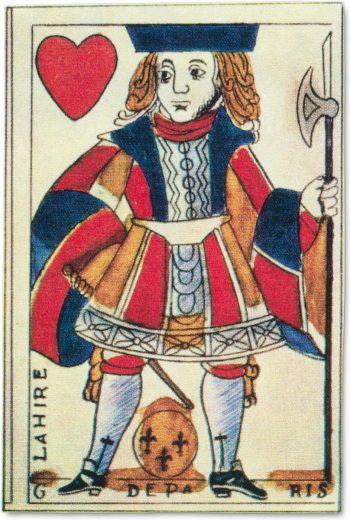

During an acute coin shortage in 1685, the Intendant of New France, Jacques de Meulles (that’s the guy who oversaw the colony’s finances), resorted to issuing playing cards to pay the troops who were stationed throughout the colony safeguarding the fur trade. Why use playing cards? It had nothing to do with the value or the suit; a jack of hearts was not worth more than a 3 of spades. Rather, playing cards back then were rigid, made of stiffer cardstock and perfect for the rigours of circulation. They were plentiful and easy to obtain. And the backs were plain, which was ideal for writing a value and for officials, including the Intendant, the Governor and the Controller of the Marine, to sign their names. To make it easier to identify the different values, the cards were cut into different shapes. Merchants were encouraged to accept the playing cards as payment with the promise that they would be exchanged for gold and silver coins when a fresh shipment arrived from France.

To date, no examples of actual playing card money have been found. This is a reproduction from a sketch created by a former archivist at Library and Archives Canada who worked at the National Archives in Paris between 1915 and 1938, and discovered documentation describing playing card money. LAC – MIKAN 2837380

To keep things quiet from the King of France, who alone held the authority to issue currency, Intendant de Meulles issued the playing cards on his own account with the full intention of redeeming and then destroying them. It was supposed to be a one-shot deal. Yet frequent shortages of coins, sometimes because the ship carrying coins would sink to the bottom of the ocean on its journey to Canada, led to repeated issues of playing card money. After a few years of continued coin shortages and no proper access to other cheap methods of financing, playing card money remained in circulation. By 1717, the issue of playing cards got so out of hand that the King passed a law banning all playing card money. However, he forced the redemption of it at only half of its face value. The estimated 960,000 livres (the currency unit in use in Canada at the time) of playing cards in circulation was finally liquidated and a total of 360,000 livres was paid out. Its devaluation wasn’t a result of the amount of playing card money in circulation, but because there were simply not enough funds in government coffers to redeem them.

Thus in 1720, the first episode of playing card money ended. Another appeared in 1729 after the debacle of John Law and his attempt to establish a central bank in France, leaving the country’s finances in tatters. But that’s another story, with, unfortunately, the same outcome.

Happy playing card day!

The Museum Blog

Notes from the Collection: Moving Forward

By: Raewyn Passmore

Notes from the Collection: A Buying Trip to Toronto

By: Paul S. Berry

Director’s chair : A little help from our friends

By: Ken Ross

The Cases are Almost Empty

By: Graham Iddon

Curators Begin Removal of Artifacts

By: Graham Iddon