Currency for extraordinary times

War is a most terrible motivator of societal change; governments rise and fall, borders shift and there is enormous social upheaval. Less dramatic, but always hand-in-hand with societal change, is war’s effect on money. Changes in the materials of currency reflect the economic necessities of war while changes of design convey the new messaging of leaders. Sometimes, special needs entail the creation of entirely new issues of money.

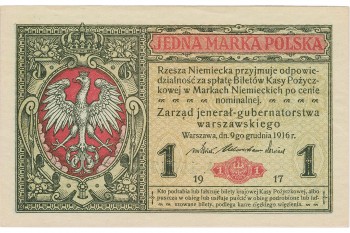

HMS Bellerophon was a “dreadnought” class battleship. The biggest of their era, such ships rarely saw battle service and were scrapped soon after the war. $10, Royal Bank of Canada, Canada, 1913 (1963.14.108)

Canadian money changed little during the First World War (WW1). On the eve of battle in 1913, The Royal Bank of Canada issued a patriotic $10 note picturing the Royal Navy battleship HMS Bellerophon. This note promoted Britain’s might in the naval arms race that had gripped Germany and the United Kingdom in the years preceding WWI. In 1917, the Canadian government also issued a patriotic $1 note that pictured Princess Patricia, the daughter of our then Governor General, the Duke of Connaught. She is the namesake of the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry Regiment, one of the first Canadian contingents to see service overseas.

Princess Patricia was not only the Governor General’s daughter but one of Queen Victoria’s grandchildren. $1, Canada, 1917 (1964.88.836)

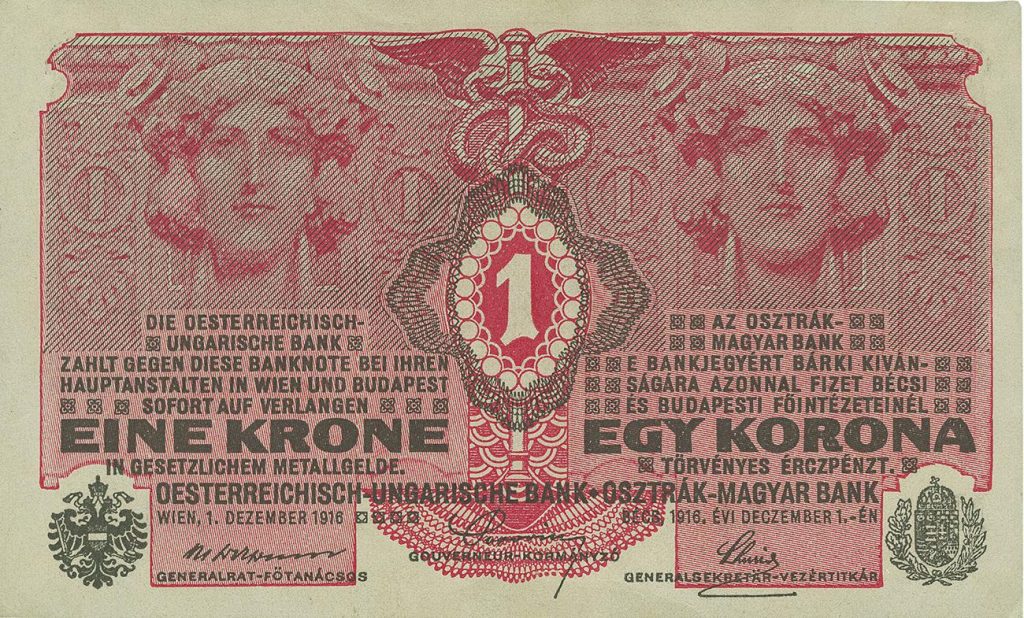

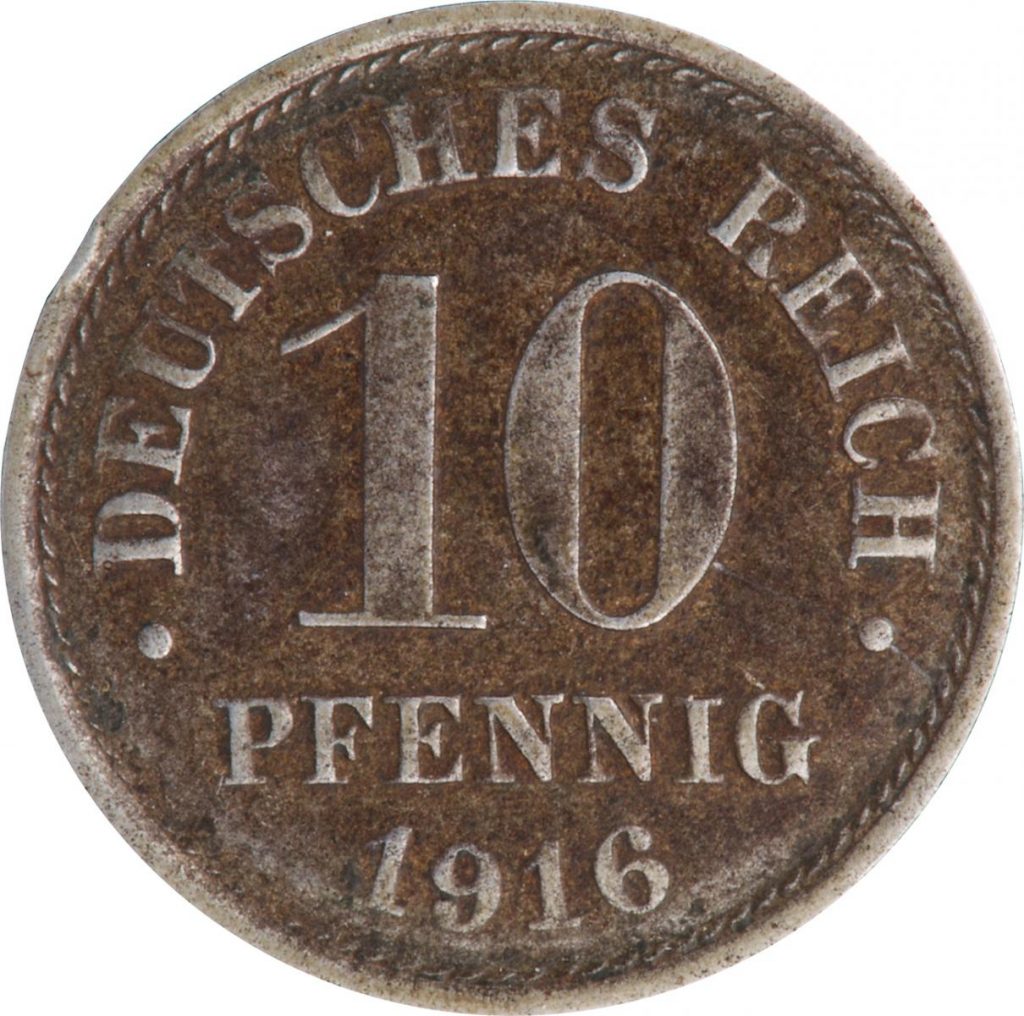

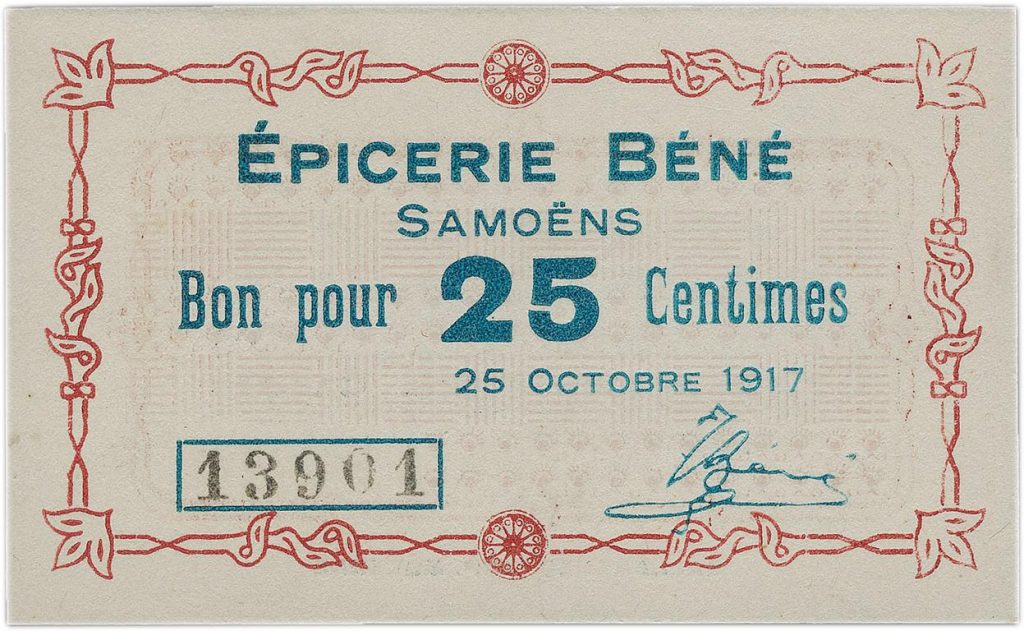

Elsewhere, change was more profound. In Europe, gold and silver coins largely disappeared from circulation as they were hoarded or as governments used the metal for the war effort. In their place nations issued low-value paper notes. The British government authorized 10-shilling and 1-pound notes to replace gold half-sovereigns and sovereigns in anticipation of the commercial need of its citizens. Governments in Germany, Austro-Hungary and the occupied countries of Belgium and Luxembourg replaced silver coins with small denomination notes or coins and tokens made from iron or zinc. Some issues, like those from Belgium, promised that they would be redeemed after the war. In parts of France, municipal chambers of commerce issued scrip using deposits in the Banque de France as collateral. The governments of Russia and Romania adopted stamp-like notes as a temporary emergency issue. Faced with diminished supplies of coinage, merchants resorted to issuing private scrip (notes) and tokens.

Similar changes rippled through the member states of Europe’s colonial empires as central authorities curtailed support of local governments. Small cards replaced coins in Morocco and Réunion (a tiny island nation east of Madagascar). Stamps were affixed to cards and issued in New Caledonia, a French protectorate in the Coral Sea east of Australia. In Senegal the government issued notes of 50 centimes to 2 francs in place of coins. The German East African Bank issued “interim” notes of rudimentary design on a wide array of papers and coins made from old brass shell casings.

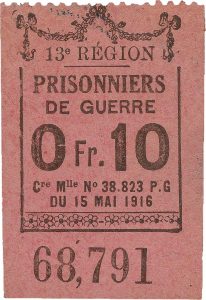

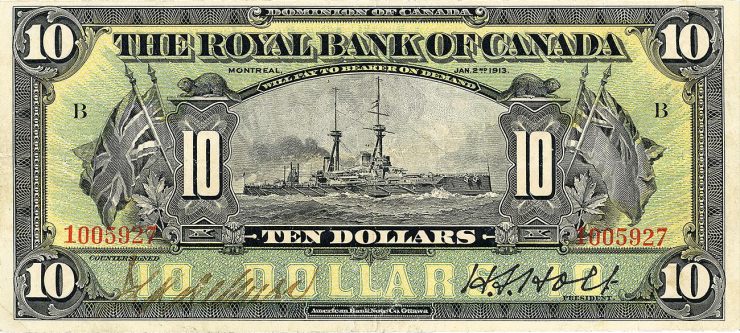

Combatants were also impacted. Military personnel used tokens in canteens or at training bases behind the lines. British forces in the Ottoman (Turkish) theatre of operations used specially overprinted notes. Captured forces on both sides of the engagement handled prisoner of war money during their incarceration. Even occupying forces in Poland issued money.

The First World War redrew the map of Europe and arguably set in motion events that led to the Second World War. Of more immediate interest though is the fascinating variety of money that emerged during the war and its aftermath. These small witnesses to the events of yesteryear speak to the difficulties of the period and the resilience of people and their governments in times of trouble.

The Museum Blog

A bank NOTE-able Woman II

By: Graham Iddon

New Acquisitions

By: Paul S. Berry

A bankNOTEable Woman

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction - Part 4

By: Graham Iddon

Decoding E-Money II

By: Graham Iddon

New Acquisitions

By: David Bergeron