The 1954 note series

Have you ever seen eyes in the bark of trees? Wolves in the clouds? Faces watching you from the abstract patterns of your mother’s bedroom drapes? Although this is a Hallowe’en blog, I’m not talking about anything supernatural, here; I’m talking about shapes that can sometimes be seen in otherwise random images or patterns—such as in the design of a bank note, for instance.

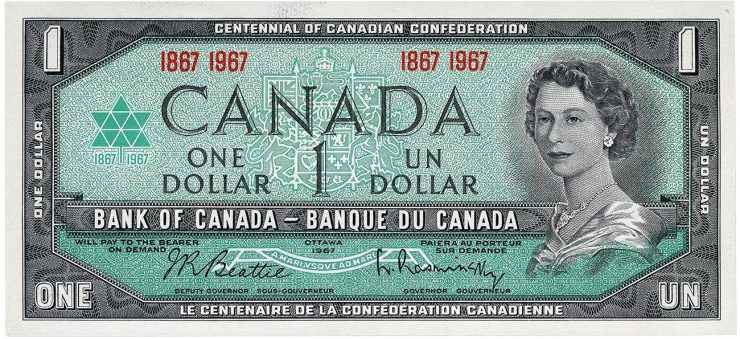

You will find nothing unusual in this centennial commemorative version of the 1954 series, but in earlier versions… $1, Canada, 1967, NCC.1967.010.001

When the Bank of Canada creates a new bank note, one important step researchers take is to ask a focus group to have a really good look at a model of the new note. A fresh perspective is crucial here to find any unintended shapes in the imagery. If anything appears to protrude from a portrait subject’s ear, or if there are faces in the background patterns, it’s best that such things are pointed out before the note has been issued. Because it wouldn’t be the first time a curious shape has appeared on a bank note.

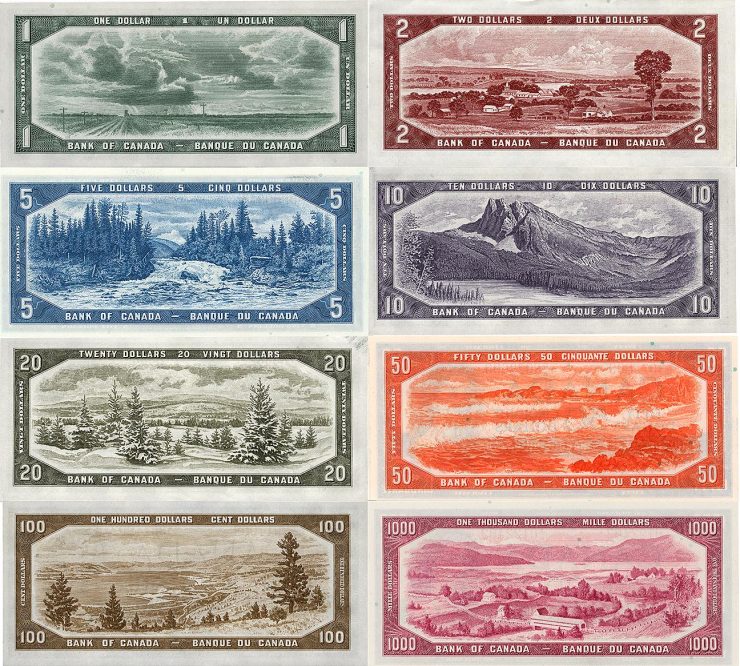

The vignettes of the 1954 series feature images from every major region of Canada.

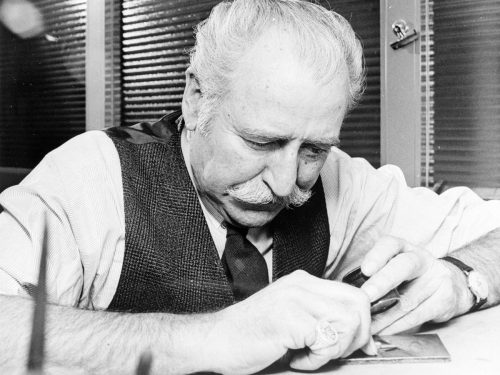

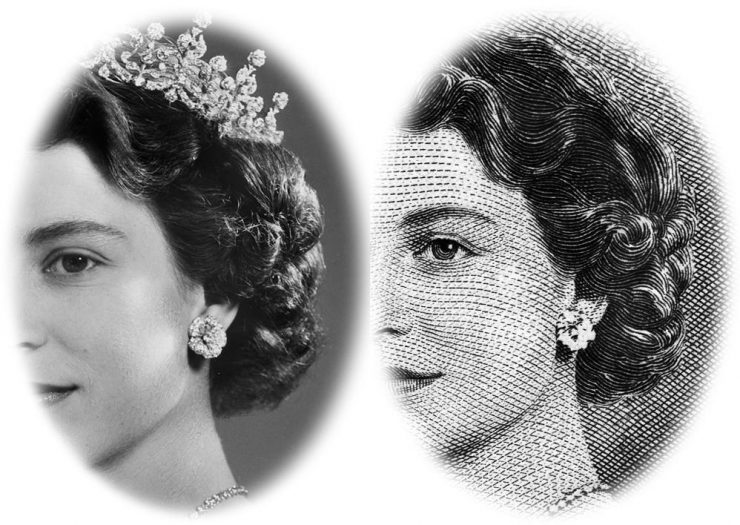

As Canada headed confidently into the 1950s, it did so with new, modern, nationalistic bank notes designed by Canadian war artist Charles Comfort. A gorgeous landscape engraving filled the back of each note while our brand-new sovereign, Elizabeth II, was the star feature on the front of all eight denominations. Celebrated Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh took an official portrait of Elizabeth. She was then beautifully reproduced by master engraver George Gundersen of the British American Bank Note Company. The new bank notes were elegant and very Canadian.

However, there was something not quite right about the engraving of the Queen; something perhaps a little sinister. Reports began surfacing of people seeing shapes in her hair—specifically the face of the Devil! In 1956, a British politician named H. L. Hogg wrote a scathing letter to the High Commissioner for Canada in the United Kingdom:

“The Devil’s face is so perfect that for the life of me I cannot think it is there other than by the fiendish design of the artist who is responsible for the drawing or the engraver who made the plate…I enclose an envelope for the return of the note but I would be better pleased if you told me you had burned it.”

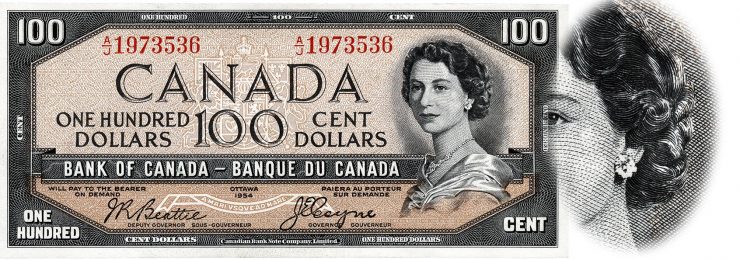

A “Devil’s Head” $100 bank note, circa 1955. The face has been enhanced slightly to make it clearer. $100, circa 1955, Canada, NCC.1987.030.002

References to the Devil’s head popped up now and again in the Canadian media from 1956 until as late as 1959. A prominent member of the coin collecting community claimed the face in the Queen’s hair was “no accident” and that, “those responsible might be trying to put across a subtle message to the public.” A number of newspapers picked up this story, spreading the idea that an insider had infiltrated the bank note printing firms. By that time, true or not, such comments would certainly have upped the interest of any “Devil’s Head” notes on the collector’s market.

All conspiracies of fiendish engravers aside, the Bank moved quickly to have the security printing companies deal with the issue. Engraver Yves Baril darkened the highlights in the Gundersen engraving and, after 1957, the series was entirely free of questionable images or of any faces but that of the Queen.

With no diabolical intention, Gundersen had actually done a remarkable job of reproducing the Karsh photograph as an engraving. The problem was that he was too good. If you take a good look at the Karsh photo and squint your eyes a bit, you can just discern above the Royal left ear some contours of hair that do resemble a face—these contours are then made clearer and arguably more demonic by the fine-lined, high-contrast etching of the engraver’s art.

The Karsh photo is on the left; the Gundersen engraving is on the right.

It would seem that Mr. Hogg should have directed his wrath not at the talented Mr. Gundersen, but at the Royal hairdresser. Unless, of course, there was a dark conspiracy involving the hairdresser, the photographer and the engraver…let me check online. Happy Hallowe’en.

The Museum Blog

The Bank of Canada Museum Goes International

By: Ken Ross

A Curator’s Favourite Task

By: David Bergeron

How’re We Doing So Far?

By: Graham Iddon

Coin designs of Emanuel Hahn

By: David Bergeron

Our Grand Opening…

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction - Part 8

By: Graham Iddon

The Yap Stone Returns

By: Graham Iddon

A New Ten on the Block

By: Graham Iddon

New Acquisitions

By: Paul S. Berry

150 Years Since Confederation

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction – Part 7

By: Graham Iddon

Coins from a nation that wasn’t: Araucania and Patagonia

By: David Bergeron