The First War Loan, November 1915

War is expensive. When Canada entered the conflict against Germany and her allies in 1914, one of the first questions MPs of the Borden government probably asked themselves was, “How are we going to pay for this?”

Historically, Canada relied on revenues from excise taxes and import duties to fund government initiatives. From time to time, this amount was supplemented by the sale of bonds to banks and brokerage firms in London and New York. With the outbreak of war in 1914, access to the British markets was restricted. So, the British Treasury lent Canada money to fund wartime operations. At the same time, we raised custom duties at home and borrowed money in New York through the sale of bonds. However, these revenue streams were insufficient to meet rising costs, so the Canadian government adopted a novel course. In November 1915, Canada looked to its own citizens to shoulder the financial burden of what would become the First World War and offered Canadians its first domestic bond issue.

Writing after the war, Finance Minister Sir Thomas White noted the cynicism expressed in 1915 over the likelihood of raising even 5 million dollars through a Canadian public bond offering—let alone the 50 million that was sought. The First War Loan of November 1915, however, proved to be an unmitigated success. When the subscription books were closed, 100 million dollars had been subscribed—double what was originally hoped for! The excess, some 50 million dollars, was used as a credit for the British government to purchase supplies in Canada such as munitions and foodstuffs. This was the first occasion that Canada, or in fact any other Dominion in the Empire, had loaned money to the mother country.

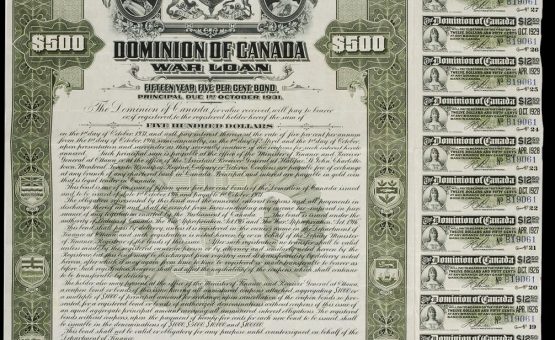

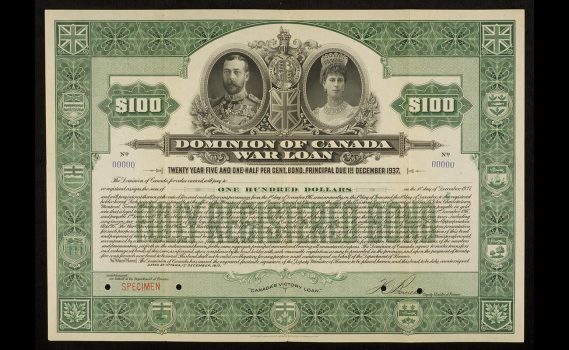

Subsequent bond issues proved even more successful and demonstrated that Canada, financially, had come of age. From 1915 and 1918 there were 5 domestic bond offerings in which Canadians pledged more than $1.7 billion. During those years, all other revenue sources combined amounted to only half that sum. Even income tax, introduced in 1918 as what was meant to be temporary measure, couldn’t raise anywhere near this amount.

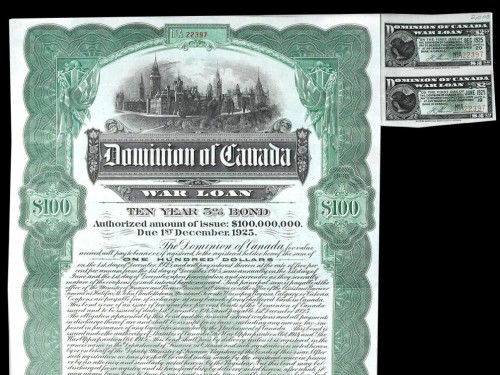

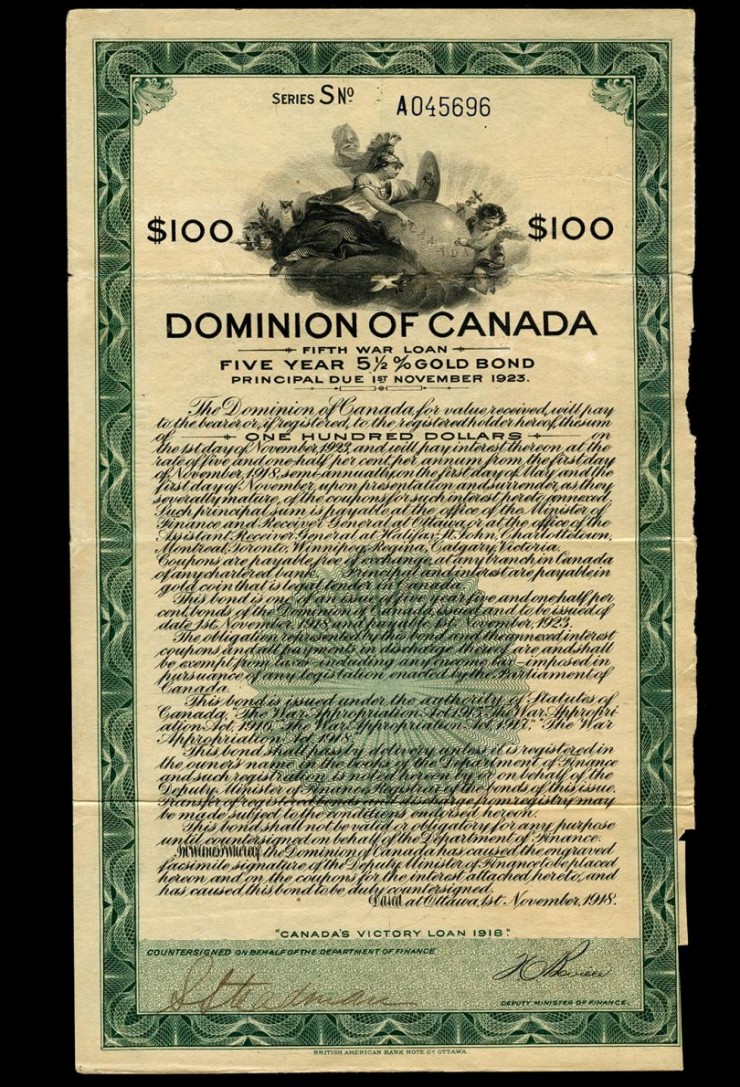

A $100 bond Fifth War Loan, December 1918. Funds from this loan were meant to cover immediate post war costs including gratuities for returning vets. Bond, $100, Canada, 1918 (NCC.2006.048.002)

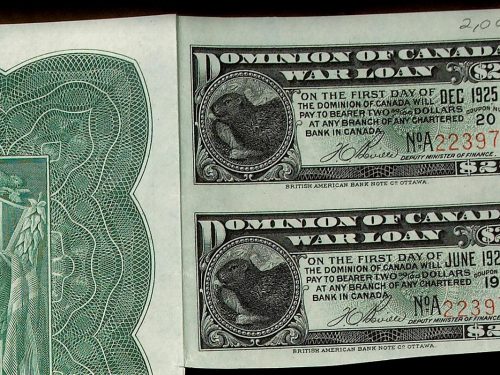

The First War Loan included bonds in denominations of up to $100,000. They matured in ten years and paid interest at 5 percent. This was in line with other commercial offerings to make the loans appealing to investors. The principal amount was repayable to buyers on December 1, 1925 (date of maturity) at any office of the Receiver General or Assistant Receiver General; interest was paid semi-annually on June 1st and December 1st at any chartered bank in Canada. Like bank notes, these bonds were printed by security printers on secure paper using special inks and decorated with intricate designs that were difficult to imitate. Patriotic images of flags, beavers, maple leaves and a view of the Parliament buildings grace the $100 bonds and make them among the most beautiful Canadian government financial instruments ever issued.

The Museum Blog

Our Grand Opening…

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction - Part 8

By: Graham Iddon

The Yap Stone Returns

By: Graham Iddon

A New Ten on the Block

By: Graham Iddon

New Acquisitions

By: Paul S. Berry

150 Years Since Confederation

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction – Part 7

By: Graham Iddon

Coins from a nation that wasn’t: Araucania and Patagonia

By: David Bergeron