A convoy arrives in Bedford Basin, Halifax NS, April 1, 1943. (The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic)

It’s 7:35 a.m., July 1st, 1940 and a shipment of fish has arrived in Halifax.

Labelled “Top Secret,” it was the culmination of almost a year of planning and preparatory work. It’s one of the war's best kept secrets—and certainly one of the most interesting. The Bank of Canada was about to become a key, if secret, player in the Second World War, and truthfully, the story doesn’t involve a single fish at all.

It involved gold. A lot of it—thousands of pounds that needed to move across an ocean to protect the future of Europe.

Imagine it’s 1940—war has broken out across the world. Germany has already annexed Austria and Czechoslovakia and invaded Poland. Within a few months, it will crush the armies of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. By May, the Germans have reached the French channel coast, surrounding close to 400,000 allied soldiers and sailors at Dunkirk.

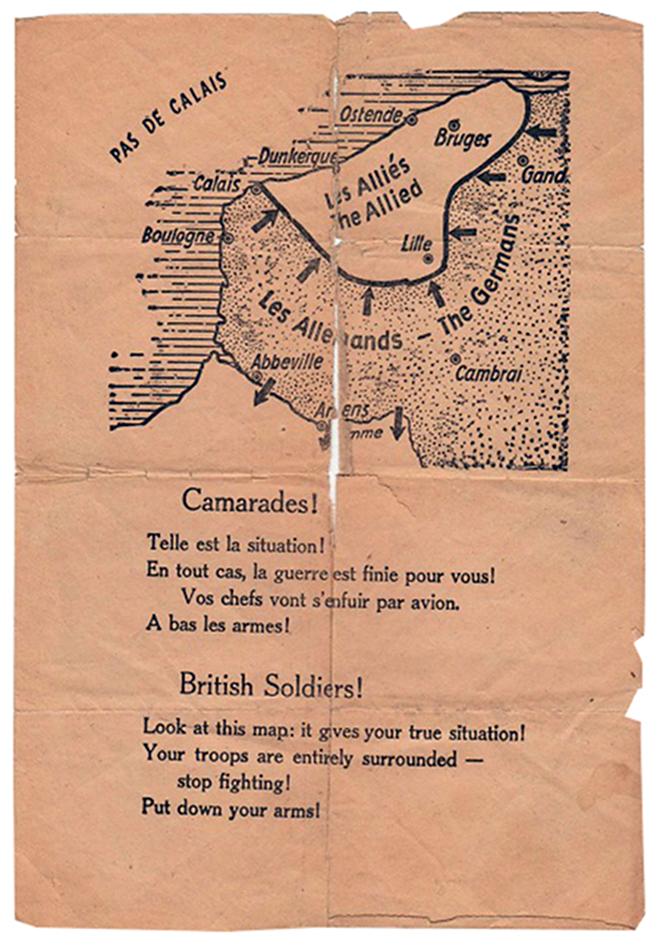

German propaganda leaflet dropped on allied soldiers at Dunkirk, Spring,1940. (Dunkirk 1940 Archives)

The United Kingdom could be the next to fall, so Churchill has developed plans to install his government in Montréal and continue to lead the Commonwealth from Canada. The Bank of England has also begun preparing for the worst—putting in motion plans to run a “shadow bank” headquartered in Ottawa. Since the Munich Agreement of 1938, it has been increasing its gold reserves in Canada as a precautionary measure. Now, with Germany at their doorstep, Churchill accelerates the process—devising Operation Fish, a plan to move England’s entire gold reserve overseas to Canada.

Sir Winston Churchill, photographed by Armenian-Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh taken December 30, 1941. (LAC R613-566)

Winston Churchill addresses UK parliament after the Dunkirk evacuation, June 4, 1940

In total, the order includes almost two thousand tonnes of both bullion and coins—including substantial holdings from the soon-to-be-captured Bank of France. The loss of any shipment would be disastrous—likely spelling Britain’s defeat. Despite a few attempts to move away from the gold standard between the world wars, the precious metal remains an important method for nations to exchange wealth. England’s gold reserves will allow Churchill to buy much-needed supplies from Canada and the United States and fund the coming war.

The convoys will also be carrying significant numbers of what were once privately held securities. Under the Emergency Powers Act, Churchill’s government confiscated them from the British public, who were forced to register their holdings at the beginning of the year. Like the gold, the securities are packaged up, shipped to Greenock, Scotland, and readied for their transatlantic voyage.

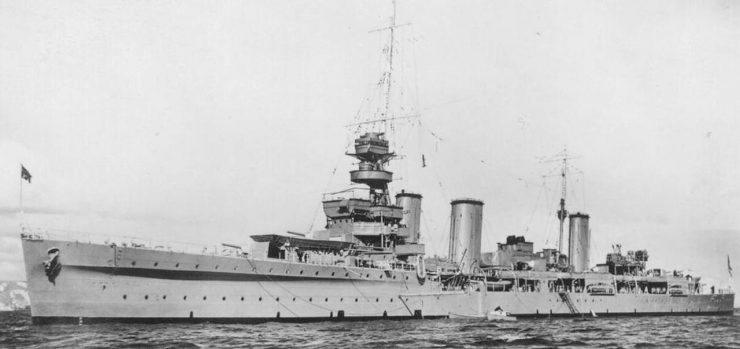

The HMS Emerald, near Chatham Dockyard, after refit. c. 1933-34. (Naval History.net)

On June 24, 1940, the first of Churchill’s convoys begins to sail, easy targets for German U-boats. The Battle of the Atlantic is well under way and the German submarine threat has reached its peak. In the month of May alone, over 100 ships were sunk—more than 40 per cent of all transatlantic traffic. The first of the gold shipments is aboard HMS Emerald. It somehow makes the 4,600 km crossing unscathed, arriving in Halifax harbour sometime around 7 a.m. on July 1st. Officials from the Bank of Canada and Canadian National Express are waiting.

The arriving boxes of “fish” are checked and re-checked before being loaded into a dozen train cars. Escorted by nearly 300 armed guards, they head for Montreal. At the Bonaventure Train Station, Alexander Craig from the Bank of England meets David Mansur, Acting Secretary of the Bank of Canada. After shaking hands, the two men oversee the splitting of the goods. The securities and cash are unloaded and sent to the Sun Life Building in Montréal, to be guarded by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The gold, however, is soon on its way to Ottawa and into the Bank of Canada’s vaults.

The Sun Life Building c.1935, Montréal and the Bank of Canada building c. 1942. (LAC PA 069265, Bank of Canada Archives PC300.5-61)

But this is only the first shipment.

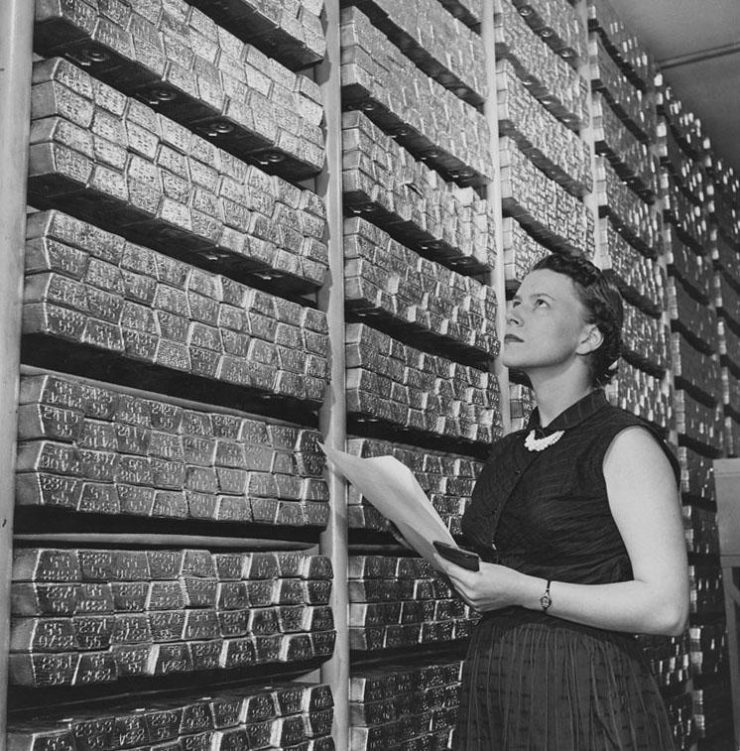

Soon, more and more convoys begin their own crossings, braving the German wolfpacks. Amazingly, not a single gold-bearing vessel is lost. By the end of Operation Fish, over 1,500 tonnes of gold ingots and coin would be placed into the Bank’s vault, where they would remain for the duration of the war. To help keep track of the gold, Mansur and the Bank hired roughly 120 retired Canadian bankers, brokers and investment firm secretaries. By their count, the Bank’s gold stores were second only to that of Fort Knox.

Miss E. Thompson, Audit Representative, checks a gold delivery in 1955. (LAC e010956367-v8)

In total, approximately $160 billion—in 2017 dollars—were shipped from the United Kingdom to Canada. More than 600 people were involved. Operation Fish was the largest movement of physical wealth in history. It was also perhaps the single greatest economic gamble of all time, and a tremendous success—a testament to the resourcefulness and co-operation of the allied powers and their central banks during the war.

The Museum Blog

Our Grand Opening…

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction - Part 8

By: Graham Iddon

The Yap Stone Returns

By: Graham Iddon

A New Ten on the Block

By: Graham Iddon

New Acquisitions

By: Paul S. Berry

150 Years Since Confederation

By: Graham Iddon

Museum Reconstruction – Part 7

By: Graham Iddon

Coins from a nation that wasn’t: Araucania and Patagonia

By: David Bergeron