The ups and downs of research

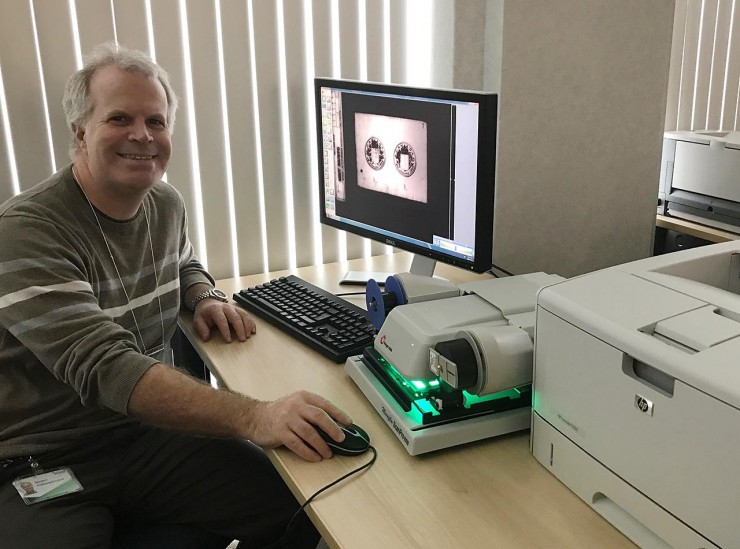

The Curator hard at work viewing documents on microfilm at Library and Archives Canada (LAC).

As a curator of the National Currency Collection, I have several key responsibilities in my job. None of them is more gratifying than conducting research about the incredible artifacts in the Collection—especially when I discover something new. Before the Internet, conducting research meant numerous trips to libraries and archives of various government and private institutions and spending long—sometimes very tedious— hours going through yards of microfilm or reams of hand-written documents. Sometimes I would come up empty-handed. Now, thanks to the Internet, access to a huge range of archival documents is virtually unlimited. Furthermore, these documents are searchable, allowing for more focused searches. Either on the Internet or in the trenches, what is required of the courageous researcher is the patience and savvy to rifle through thousands—even millions—of documents to find the proverbial “needle in a haystack.” A recent research endeavour challenged me to find a very small needle in a very large stack of hay indeed.

In the fall of 2016, I was invited to give a presentation at the Central States Numismatic Society’s (CSNS) semi-annual educational forum to be held in May 2017 in Windsor, Ontario. The CSNS has more than 2,000 members from 13 American Midwestern states and includes members of the Windsor Coin Club. The club president requested that I give a talk about the design competition for the Canadian coin series of 1937—the year that the coins with those iconic images we are so familiar with were first put into circulation. As 2017 marked the 80th anniversary of the issue, it was an appropriate time to present this topic.

For my research on the 1937 coin-modernization program and its design competition, I relied on a book called Striking Impressions by Dr. James A. Haxby. A former deputy curator of the National Currency Collection, Haxby provided important insights into the evolution of Canada’s coinage. Sadly, he never listed his research sources. Knowing that the additional information had to exist, I set about finding my evidence.

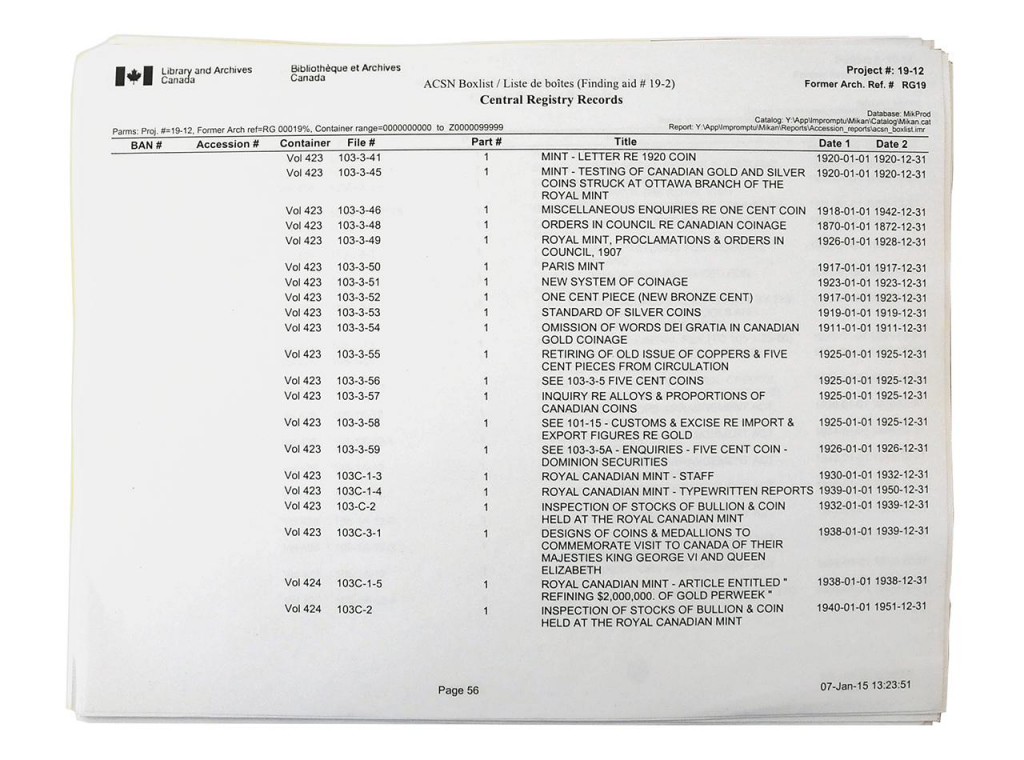

A logical place to begin my search was the records of the Royal Canadian Mint held at Library and Archives Canada. Flipping through the finding aid (a type of index that helps researchers navigate through multiple documents), I was surprised to see little information about early coin designs. The size of a record (or fond) is measured in linear metres, as if the papers and file folders were stacked flat. The thickness of a file folder with 25 sheets of paper inside is about 1 centimetre. The Royal Canadian Mint fonds at LAC measure 15 metres!

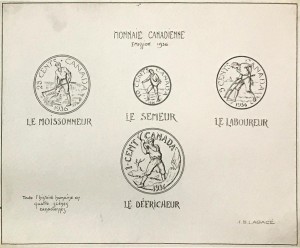

However, I made some interesting discoveries. One box contained original sketches by three artists who had submitted designs for the competition: Sylvia Daoust, Henri Hébert and Jean-Baptiste Lagacé. It was the first time that I learned about these Montréal artists and their submissions. Haxby did not mention them in his book. Beyond that, the finding aids gave no indication of records related to the 1937 coin-modernization program. It was a mystery to me where Haxby got his information. I had to expand my search.

It was perhaps by mere chance that I discovered several volumes of correspondence between the Master of the Royal Canadian Mint and the Deputy Minister of Finance. I had hit the jackpot…at least I thought I had.

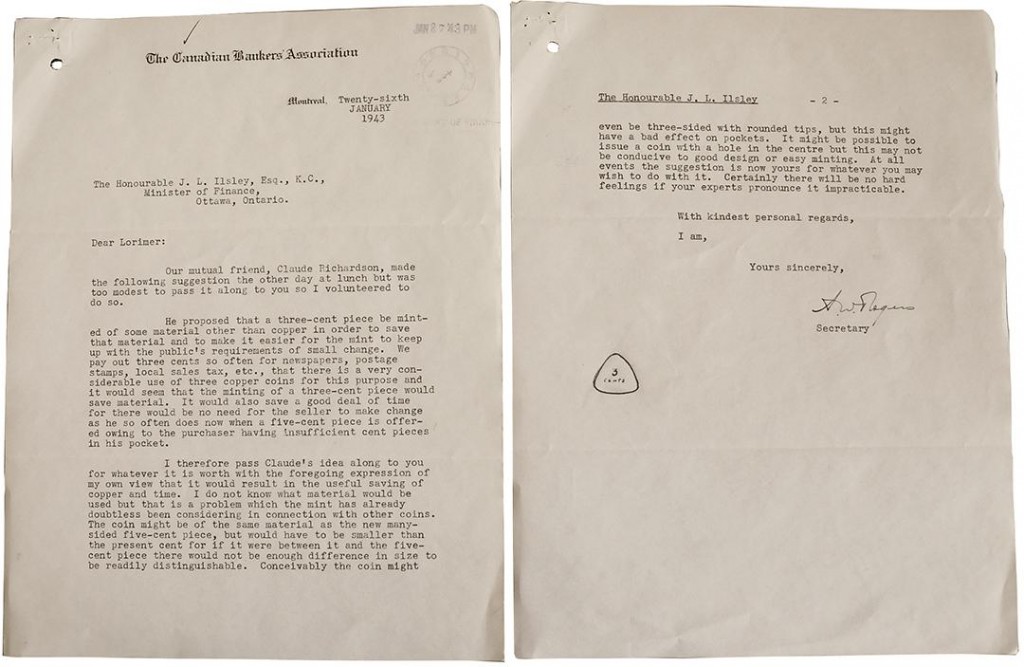

The correspondence of the Deputy Minister alone measures more than 62 linear metres. That’s 2/3 the length of a football field. There were letters about the reduction of the size of the cent in 1920 and the switch from silver to nickel for the 5-cent piece in 1922. A whole volume was devoted to the celebration of the diamond jubilee of Canadian Confederation and there was correspondence about the 1935 silver dollar. I was excited thinking that I was on the verge of finding exactly what I needed. Alas, there was a giant void where records about the 1937 coin-design competition should have been.

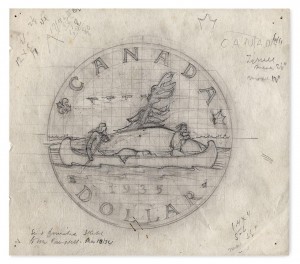

Fortunately, the National Currency Collection has Emanuel Hahn’s correspondence concerning the ’37 design competition. Hahn designed our quarter, dime and the voyageur silver dollar. The Collection also holds production material used in the manufacturing of the dies as well as Hahn’s sketches and those of another entrant in the competition, Robert Tait McKenzie. I still had substance on which to build my talk.

It remains somewhat of a mystery whether correspondence about the 1937 coin-modernization program even exists and, if so, where it could be. Maybe while I’m researching something else, such as the mystery of the lost voyageur dollar dies of 1987, I’ll find a stray folder about our iconic 1937 coinage—the perpetual struggle of the curatorial researcher.

P.S. If any of you readers happen to be researching Canadian coinage and encounter any information about the 1937 coin-modernization program, .

The Museum Blog

Notes from the Collection: Moving Forward

By: Raewyn Passmore

Notes from the Collection: A Buying Trip to Toronto

By: Paul S. Berry

Director’s chair : A little help from our friends

By: Ken Ross

The Cases are Almost Empty

By: Graham Iddon

Curators Begin Removal of Artifacts

By: Graham Iddon

Notes from the Collection : 2013 RCNA Convention Winnipeg

By: David Bergeron

First Artifacts to Leave the Museum: And they were big

By: Graham Iddon

Director’s chair : “I don’t know why you say goodbye, I say hello.”

By: Ken Ross

Remembering Alex Colville (1920-2013)

By: Raewyn Passmore

Farewell to the Currency Museum c.1980

By: Graham Iddon