During the planning stages stamping the word ‘final’ on any given aspect of a travelling exhibition can seem less of a directive and more of an overly optimistic suggestion. An exhibition’s elements are changeable for so many reasons, by so many people, that there is a strong temptation - to paraphrase Yogi Berra - to say it’s only done when it’s done. Better still, it’s only done when it has been built, toured and dismantled. All of which is to say that one must be careful about using the word ‘final’ - it’s so, well, final.

The Collections department of any museum, passionate though it may be about telling the stories that live in its vaults, has a mandate to maintain its artifacts under the best conditions possible. The exhibitions team of any given museum understand and support this, but is still primarily focused on the goal of sticking the pieces on display. And here you have the basic family conflict of every museum team: the brother and sister who both want to sit in the front seat on car trips. (for those of our readers old enough to remember cars that could seat 3 in the front) This can make choosing artifacts a little bit complicated.

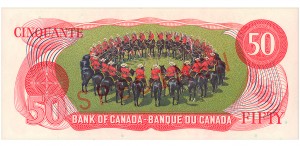

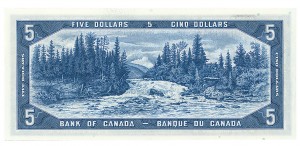

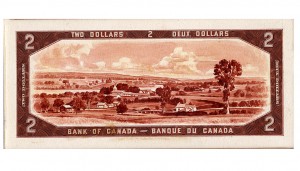

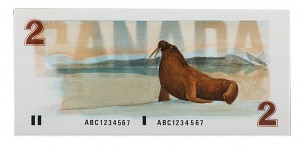

Unlike a permanent exhibition, travelling exhibitions suffer all sorts of shifts in temperature, humidity, lighting—not to mention the risks of loss, damage or acts of God (i.e., ten year old boys). So selecting artifacts begins to resemble a form of hostage negotiation. It starts with: ‘What artifacts would tell this story best?’. Then: ‘What artifacts do we have in the collection that will do this?’ Followed by: ‘Which of these items are suitable for travel and display?’ That last one is a doozy: ‘I’ll give you four months at 75 lux of light at 60% humidity’ ‘Hmm, how about six months at 50 lux of light at 55% humidity?’ ‘Fine, but I want a sealed case.’ ‘Yeah, um, let me take a look at the budget… ’ OK, it’s not really like that, (the conservator decides what’s best), but the needs of the object and those of the exhibition are often very different. The good news is that, at the end of the back and forth, as is evident in our current effort, there are always, plenty of beautiful and unusual things on offer.

One of the reasons we have had to be so careful in the case of this exhibition is the fact it is designed to be on the road for several years. During that period, there will be times when some of the artifacts will need to come home for a bit of a rest. They could be in Rimouski or Prince Albert when the need arises, so rather than take them out of the story, we include reproductions (noted as such) that can be swapped for the real thing, each with its own little case so nobody handles the artifacts. The risk of damage to the item is minimized on all accounts and everybody’s satisfied.

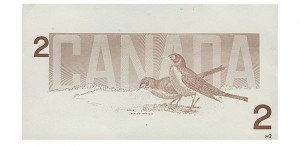

These days we are continuing with our exhibition planning; so far so good for Voices from the Engraver. I think we can safely say the examples you see here are ‘finals’ (although, maybe, uh, let me get back to you on that).

Next time we’ll talk about the stamps which make up roughly half of our artifacts.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon