What is money but not money?

By: Raewyn Passmore, Assistant Curator

What do you think of when you think of money? Do you think of coins? Bank notes? Three-hundred years ago, people weren’t sure that bank notes were actually money. It took a long time for them to get accustomed to the idea, but bank notes are the most common type of currency used today. Bus tickets, store cards and coupons are also a sort of money: they have value that can be exchanged for something else. The new additions to the National Currency Collection described below demonstrate some of the different kinds of money we use or are willing to accept.

France’s first bank notes

Before the advent of television, radio or even national newspapers, the French government distributed pamphlets to inform people about new laws. The National Currency Collection has recently acquired original pamphlets from the years 1716 to 1720, when France and its colonies were facing financial disaster.

The French king, Louis XIV, had emptied the royal coffers on expensive wars and extravagant projects such as construction of the palace of Versailles. When he died in 1715, he left the country bankrupt. Scottish economist John Law came to the rescue with his new financial “system,” which involved the introduction of paper money. The people of France weren’t ready for Law’s ideas, however, and the scheme eventually collapsed.

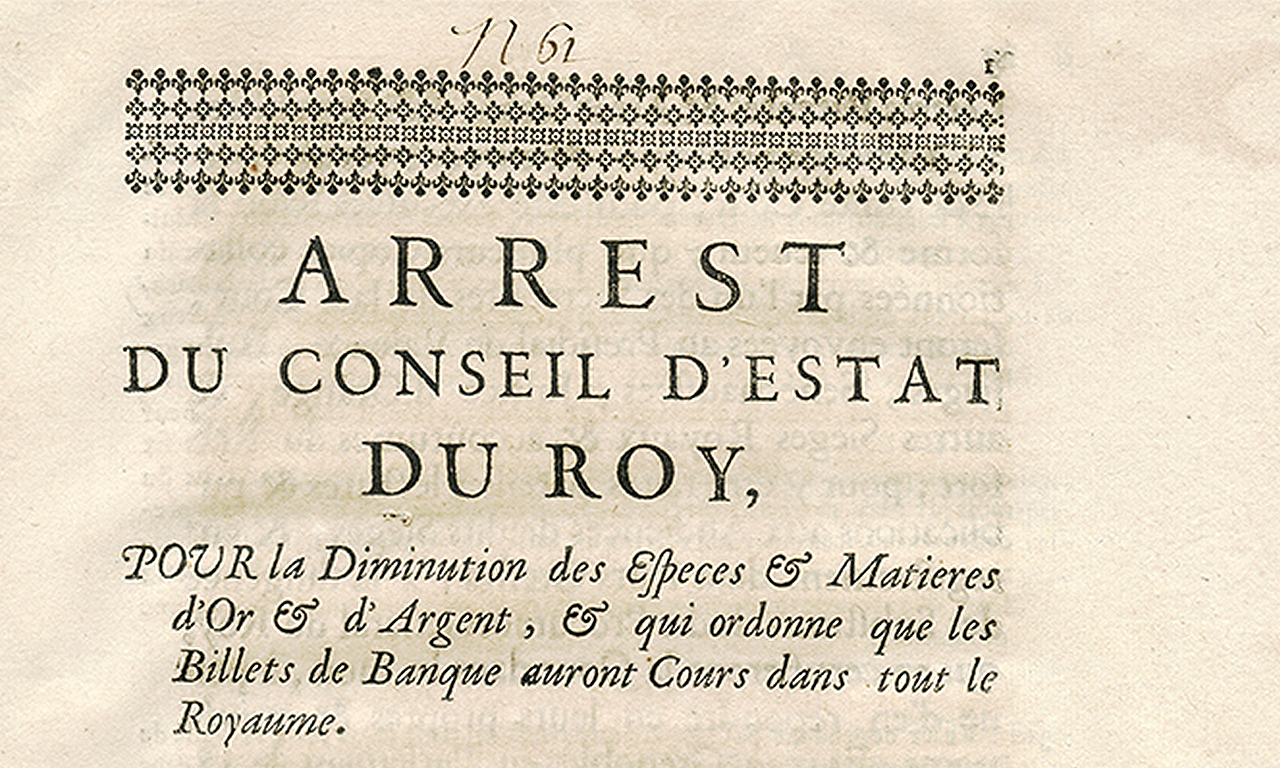

NCC 2013.73.3, 179 x 233 mm: Edict of the King’s Council of State (Arrêt du Conseil d'État du Roi), issued in Paris, January 20th, 1720.

This pamphlet decreed banknotes legal tender throughout the kingdom (including New France) and restricted the use of gold and silver coins. Basically, the government tried to force people to use paper by making it harder to use other kinds of money.

Tea tokens from Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar

Tea is an important part of daily life in Turkey. But the merchants in the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul don’t use coins or notes to pay for their tea; they use plastic tokens. Merchants purchase them in bulk from local tea houses. Each token is good for one glass of tea and each tea house will only accept its own tokens. Throughout the day, runners deliver tea to the merchants and their customers. The Collection’s tokens are square and bear the Turkish word for tea: “Çay” (pronounced chai).

There are many different kinds of tokens in the National Currency Collection. In 19th-century Canada, merchants frequently distributed tokens that could be redeemed for goods or services. We still use tokens today. We’re all probably familiar with tokens for drinks, the subway or the arcade.

These are the first Turkish tea tokens in the Collection and we would like to learn more about them. Have you seen or used tea tokens in Turkey or elsewhere? Let us know by mail or .

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon