Explore treaties using art, artifacts and historical thinking.

Overview

While analyzing artifacts and art, students have the opportunity to apply the skills of historical thinking and consider their role as a Treaty partner.

Big idea

Examining artifacts from the past and contemporary art can help us understand the relationships and ongoing relevance of Treaties between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown.

Total time

160 minutes. Each activity may be delivered as a standalone lesson of 40–60 minutes or as a part of a sequenced set of learning experiences. The activities are best delivered in the order they appear.

Grade levels

Grades 7–12; Secondary I–V and CEGEP

Subject areas

Social studies

- Governance and rights

- Crown relationship with Indigenous nations

- Changing relationships with Indigenous peoples/nations over time

- Political and legal rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Treaty education and reconciliation

History

- Expansion after Confederation

- Economies of Indigenous Peoples

- The fur trade and relationships between settlers and Indigenous Peoples

- Historical perspectives on colonialism and colonial governments

- Causes and consequences of treaties

- Continuity and change of Treaty relationships

Learning objectives

Students will:

- examine relationships between Indigenous Peoples and Europeans during the fur trade era

- explore the role of gift giving as part of diplomacy and the symbols associated with Treaty relationships

- explore the history behind the $5 Treaty annuity

- contrast historic and modern Treaty celebrations

- draw connections between Métis scrip and the Numbered Treaties, considering the aims of the Canadian government and effects on Indigenous Peoples

- examine the misconceptions and stereotypes associated with First Nations’ Treaty benefits

Materials

Classroom supplies and technology

- Whiteboard and markers

- Students’ own notebooks

- Computers or tablets with internet access for students

- A computer with a projector and speakers or an interactive whiteboard with audio

- Timer

Worksheets

- “Symbols of diplomacy” (two cards, double-sided)

- “Investigating artifacts” (one set of pages per student)

- “Free Ride by Frank Shebageget” (one poster-sized page per class, printed or shared digitally)

- “Answer key – Investigating artifacts” (one set of pages for teacher reference)

Online resources

From the Bank of Canada Museum:

From the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba:

Other:

- “Treaties with Indigenous people in Canada” from the CBC

- “Treaty annuity payments” from Indigenous Services Canada

Activity 1: Trade-based relationships

Students examine relationships between Indigenous Peoples and Europeans during the fur trade era by focusing on Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) trade tokens.

Time

20 minutes

1.1 Opening discussion

Draw the following Venn diagram on the whiteboard:

Draw a Venn diagram on the board where one circle is labelled “Indigenous Peoples” and the other is labelled “Europeans.”

Explain that trade between Indigenous Peoples and Europeans was foundational to their relationship. The fur trade was not only the reason for European interest in this land, but also the activity that drew both cultures together. The fur trade could not have existed without Indigenous trappers and guides. In return for furs and their services as guides and Knowledge Keepers, Indigenous peoples received goods from Europeans. Both groups were trading for things they wanted or needed, but also traded and gifted different things to strengthen relationships.

Ask your students: What would Indigenous Peoples offer for trade? What would Europeans offer?

As the class brainstorms answers, capture these ideas in the outer rings of the Venn diagram.

Then, write the results of these trade-based relationships in the diagram overlap. Answers may include:

- new technologies (e.g., canoes, snowshoes, guns, manufactured clothing)

- symbolic objects and tokens of the trade relationship

- cultural exchange (e.g., religion, customs, style)

Read more in the Museum’s blog post “Fur Trade Economics.”

1.2 Minds-on activity

Using a projector or interactive whiteboard, show the images below of a half made beaver token. Don’t reveal yet what it is called. Explain that these are images of an artifact from the Museum’s collection. The token is primary source evidence from the past.

Artifacts are evidence from the past. What can this token tell us about the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the Hudson’s Bay Company?

Source: ½ made beaver, token, Hudson’s Bay Company, Eastmain District, around 1860, NCC 1973.81.2.1

Have students examine the artifact. Make sure to show both sides of the token. Ask the students:

- What do you think this is?

- Who would have made this item? Why?

- In the trade relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the HBC, how would this have been used? Why?

Explain that, by the 1820s, the HBC had become one of the most powerful trading companies in North America. Most furs traded at HBC posts were trapped by Indigenous peoples, who exchanged them for goods. When an Indigenous trapper brought furs into an HBC post, the company employee laid out tokens on the counter representing the value of those furs. A token’s base value was one beaver pelt, which is why it was called a made beaver. The employee would then remove tokens as the trapper selected goods to buy—using the tokens like a manual calculator.

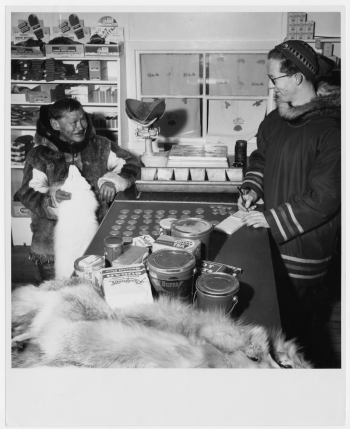

An HBC clerk and an Inuk trapper using tokens to tabulate a transaction.

Source: Richard Harrington, “HBC clerk Victor Pearson with trapper William Ningeok,” Inukjuak (Port Harrison), March 1959, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Manitoba Archives, 1987/363-E-383/5.

1.3 Discussion

Ask your students:

- What ethical dimensions arise from using tokens as part of the fur trade relationship?

- Is the value of furs and tokens clearly understood or communicated?

- Who sets the value for the fur and for the goods exchanged?

- Does each culture value the same things?

- Who benefits most from this exchange? In what ways?

Activity 2: Diplomacy, gift giving and symbols

Students examine the symbols associated with Treaty relationships and explore the role of gift giving as part of diplomacy.

Time

40 minutes

2.1 Circle activity and opening discussion

Ask students to select an item from their pencil case, backpack or binder that they would feel comfortable giving as a symbol of friendship. Explain that the item will be returned after the activity.

Invite students to sit in a circle. Ask one student to gift their item to the person next to them. After the second student has received their gift, they must turn to their other side and gift either their own item or the one they just received. This gift giving should continue around the circle until everyone has received a gift.

Bring the class together for an all-group discussion. Ask students:

- What item did you gift? Why?

- How could the item you received be used as a reminder and a symbol of friendship?

Explain that gift giving or gift exchanges are part of long-held protocols associated with many diplomatic relationships.

Before Confederation, gift giving between Indigenous Peoples and their Indigenous and European partners was based on reciprocity and it was part of long-held protocols associated with relationship building. These tangible gifts often became symbols of enduring relationships between the gift giver and the recipient.

Building strong relationships was critical to the economic well-being of Indigenous communities, which relied on their neighbours for support during hard times.

Today, gift giving is still an important protocol for relationship-building between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Ask the students to return their gifts to the original owners.

2.2 Hands-on activity

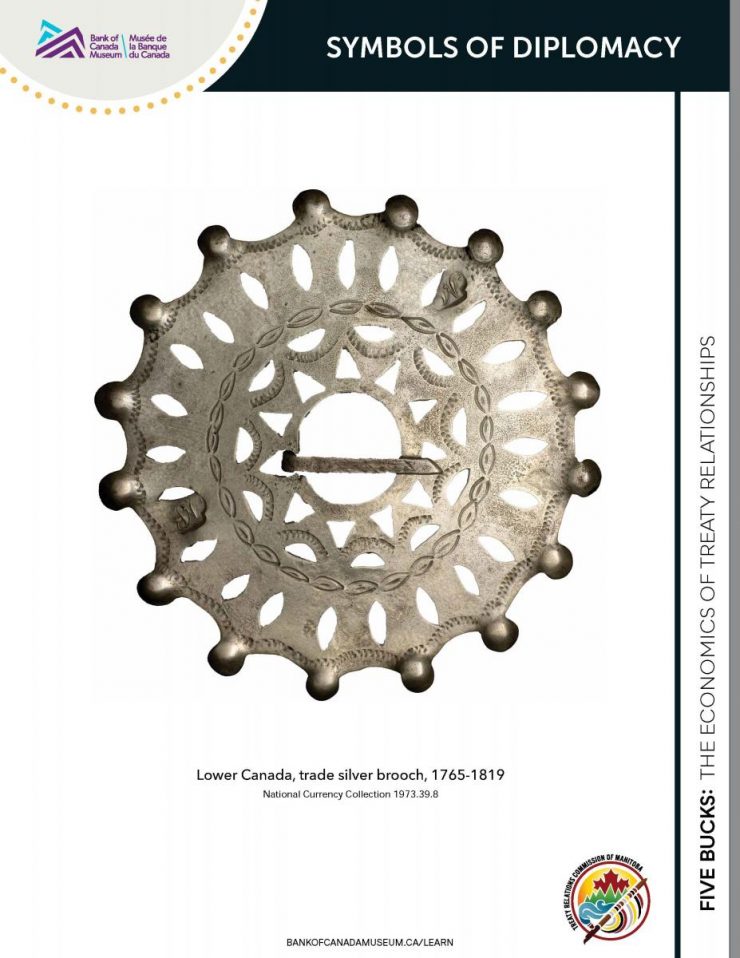

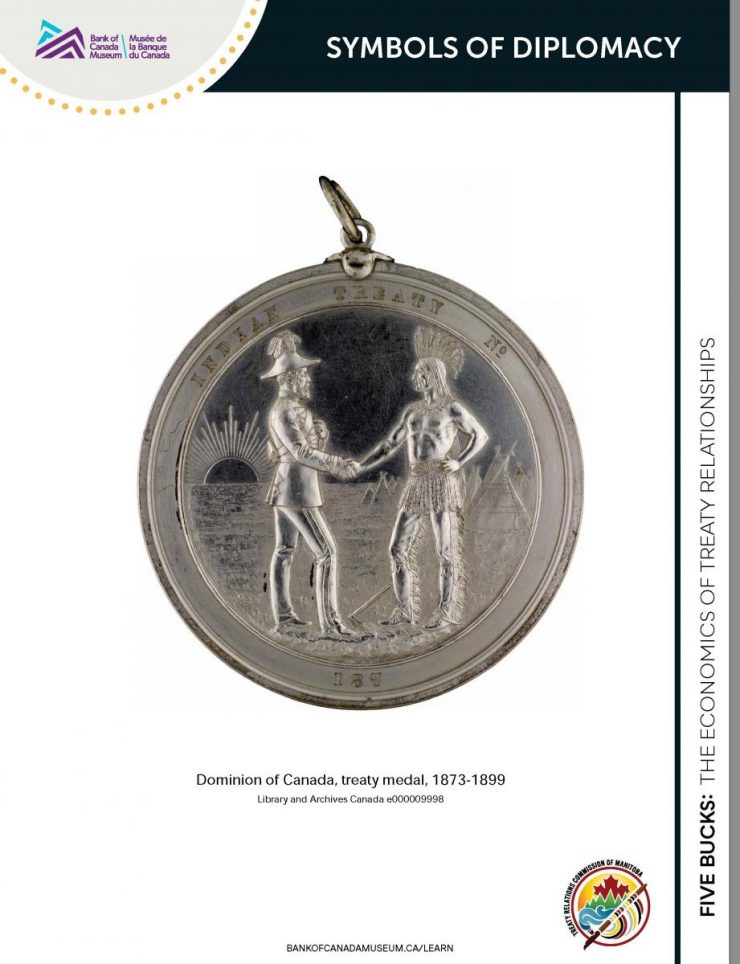

Tape up the two artifact cards found in the worksheet “Symbols of diplomacy” where students can easily view and access them.

Display these cards, depicting a trade silver brooch and a Treaty medal, on the wall. Invite students to see, think and wonder about them.

Invite the students to do a gallery walk and view the images. Guide them through “See, Think, Wonder” strategy of inquiry:

- See—Students carefully observe and describe what they see in each image.

- Think—Students interpret what they have observed.

- Wonder—Students ask questions about what they have observed and interpreted.

They should make notes on their gallery walk. Then instruct them to return to their seats.

Ask:

- What are these artifacts?

- Have you seen them before? If so, where?

- What do you think they symbolize?

- In what ways are symbols important reminders of relationships?

- What questions do you have about them?

Share the information on the back of the cards, either orally or digitally, to answer any questions the students have about the artifacts.

Activity 3: Five bucks, five bucks, five bucks

Students explore the history behind the $5 Treaty annuity, contrast historic and modern Treaty celebrations, and apply research skills when investigating Canadian currency from the 1870s.

Time

40 minutes

3.1 Opening discussion

Show your students the video “Treaties with Indigenous people in Canada” [2:41].

Explain to them that eleven Numbered Treaties were signed between First Nations and the Crown (the Canadian government) from 1871 to 1911. Part of these Treaty agreements are yearly annuity payments. Status Indians—or Treaty Indians—as identified in the Indian Act are entitled to an annual payment of $5 from the federal government. (Citizens in Treaty 9 receive $4.) Many First Nations see this small payment as a reminder of the Treaty relationship.

Annuity recipients in the late 19th and early 20th centuries would have been able to afford a lot more with their payments than they do today. For example, $5 in 1914 would be worth about $133 in 2024. The rise of prices over time is called inflation. Because of inflation, the annuity payments, which might once have helped Indigenous people pay for their expenses, are mainly symbolic today.

3.2 Hands-on activity

Divide students into pairs. Give each pair a copy of the worksheet “Investigating artifacts”.

Explain that the Canadian government issued its first bank notes in 1870. For Numbered Treaties 1 to 10, the government of that time would have used one- and two-dollar notes (also known as small notes) like these to pay Treaty annuities. The government did not issue a five-dollar note until 1912.

Tell students that they will use their understanding of artifacts and how to ask good questions to learn more about these objects. Instruct the pairs to complete the worksheet together.

When they are finished, bring the students together to discuss their answers as a whole class. Refer to the answer key if needed.

3.3 Discussion

Ask your students:

- What do you think Treaty Day gatherings looked like 150 years ago? What has changed? What has stayed the same?

- Government officials used to travel to First Nations communities to make Treaty annuity payments. Treaty members would gather at band offices or other gathering places to receive their payments. Often, a census of the population was taken at the same time, and doctors sometimes travelled with Treaty officials to provide vaccinations or other medical services.

- More recently, some First Nations host festivals or celebrations to mark Treaty Day. Most annuities today are paid electronically, or by a cheque in the mail.

Activity 4: Two sides of the same coin

Students draw connections between Métis scrip and the Numbered Treaties, considering the aims of the Canadian government and their effects on Indigenous Peoples.

Time

40 minutes

4.1 Opening discussion

Write the following on the whiteboard:

- “The early bird gets the worm.”

- “It’s raining cats and dogs.”

- “Once in a blue moon”

Ask your students: What do all of these have in common? [Answer: They are all idioms.]

Explain that an idiom is an expression that often uses a figurative, non-literal image to convey an idea (for example, “clear as mud”).

Add one more idiom to the list:

- “two sides of the same coin”

Explain that this idiom refers to two distinct parts of the same thing.

Divide the whiteboard into two sections. Write the headings “Métis scrip” above one section and “Numbered Treaties” above the other.

Tell the class to copy the columns and headings in their notebooks or on a device.

4.2 Hands-on activity

Explain to the students that they will be doing two short free-range research activities. Tell them you will give them a set amount of time, and ask them to research each of the two topics identified in activity 4.1, one at a time. They can use search engines on their computers or tablets, their class notes, a textbook, etc. You can also refer them to these sources:

- Library and Archives Canada

- Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada (Canadian Geographic)

- Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture

- The Canadian Encyclopedia

- We Are All Treaty People (Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba)

In their notes, instruct them to take short, concise notes about each topic. Remind them to consider the five Ws (Who? What? When? Where? Why?)

Tell them to not worry about spelling or grammar. They should focus on capturing important ideas.

Set the timer for between three and five minutes. Begin topic 1: Métis Scrip.

Once the timer has buzzed and the students have completed their research, invite the class to share what they learned. Capture their ideas on the whiteboard the first section. Fill in any gaps, as needed. Then share the following images of a Métis scrip document on a projector or interactive whiteboard.

Certificates like this were issued to Métis between 1875 and 1921 to settle land claims.

Source: Library and Archives Canada; Department of the Interior fonds; Dominion Lands Branch; e011319101

Set the timer again and have students repeat the activity with topic 2: Numbered Treaties.

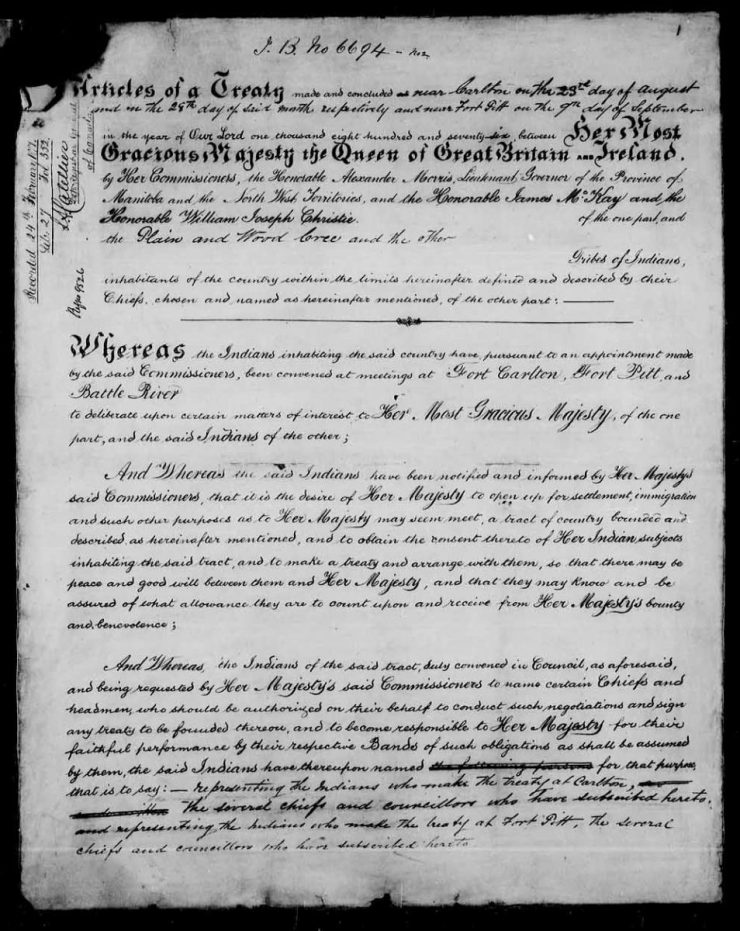

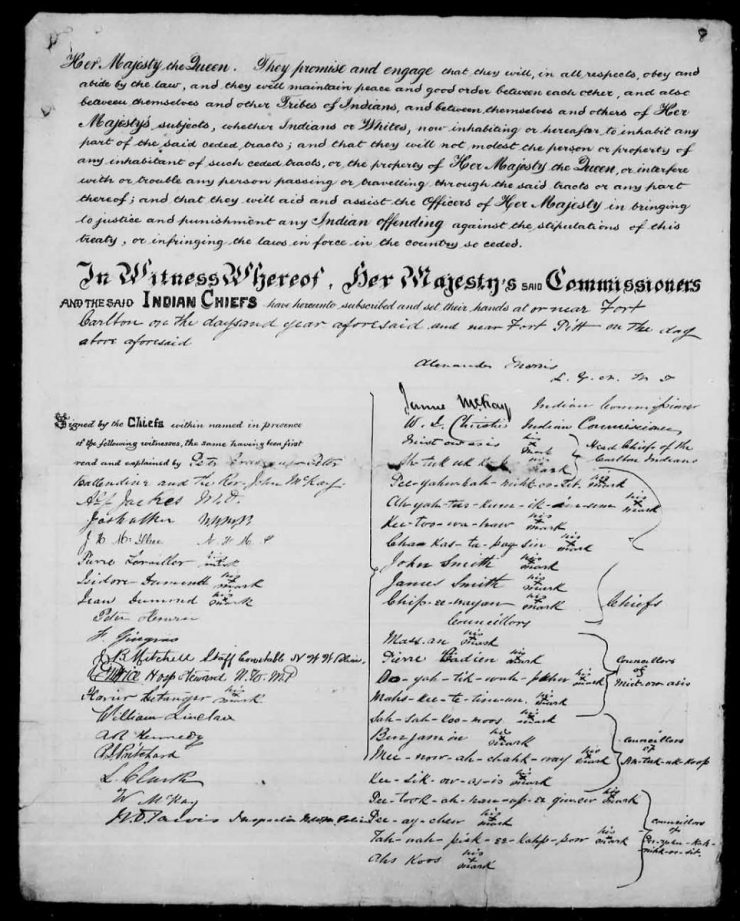

Once they have completed their research, invite the class to share. Capture their ideas in the second section on the whiteboard. Fill in any gaps, as needed. Then, share the following image of a Treaty document.

This is the handwritten text for Treaty 6, signed on August 23, 1876, by the Canadian government and Cree, Assiniboine and Ojibwe leaders. It covers parts of present-day Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Source: Library and Archives Canada; Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development fonds; e002995359

Bring the class together in a discussion. Leave the two topics and their lists of ideas up on the board, so students can consult and add to them, as needed.

Recap the following for understanding:

Métis scrip

- Beginning in 1870, the Canadian government issued scrip (a certificate) to Métis living in the West.

- These certificates, called Métis scrip, were used in place of actual money and were redeemable for land or money. In exchange, the Métis gave up their Aboriginal title, which was defined in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 as the exclusive rights that Indigenous people had to all lands not ceded by or purchased from them.

- In the Manitoba Act of 1870 and the Dominion Lands Act of 1872, the Canadian government had promised to provide the Métis with grants of land, but the scrip process was complicated and disorganized. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in 2013 that this process did not deliver on the promises of the Manitoba Act.

Numbered treaties

- The Numbered Treaties are 11 treaties between the Crown (the government of Canada) and First Nations. They were signed between 1871 and 1921 and covered a vast area of Canada, from northern Ontario to the Rocky Mountains.

- After Confederation, the Canadian government wanted to expand the country westward. To do that, it needed access to Indigenous lands. The Numbered Treaties provided this, and in exchange, the government promised that First Nations would receive certain rights and benefits, including reserves and annuity payments.

- The Treaties were interpreted differently by First Nations and the government. First Nations believed the Treaties were an agreement to share the land, whereas the government believed they were an agreement for First Nations to surrender their land.

Ask students:

- What are the similarities between Métis scrip and the Numbered Treaties?

- How are they “two sides of the same coin”?

- Both scrip and Numbered Treaties were a way for the Canadian government to remove Indigenous peoples from their lands. By extinguishing their Aboriginal title, the government could use the land for new settlers and for economic activities such as mining and logging.

4.3 Discussion

Read “Who benefits from Treaties?” aloud to your students or ask them to read it on their devices.

Ask students to reflect on what they’ve learned. Then discuss this in groups, or ask the students to write a journal entry in their notebooks or devices.

Activity 5: Free Ride

Students examine the misconceptions and stereotypes associated with First Nations’ Treaty benefits using Frank Shebageget’s artwork Free Ride as a source of their learning.

Time

20 minutes

5.1 Opening discussion

Tape up a printed copy of the poster “Free Ride by Frank Shebageget,” showing an image of his artwork Free Ride, or share it with students digitally.

Give the students a couple of minutes to view the artwork. Then guide them in a discussion by asking:

- What do you notice?

- Can you describe the artistic features, such as line, shape, colour, composition, material and subject matter?

Show the artwork again, and remind students that when interpreting art, there is no right or wrong answer. Ask leading questions such as:

- What is the mood or feeling that the artwork evokes?

- What does this work of art remind you of? Why?

- How does this work of art relate to an aspect of your own life?

5.2 Minds-on activity

Focus on the artwork’s title, Free Ride. Ask students:

- What does the idiom “free ride” mean?

- Does it have a positive, neutral or negative connotation?

- Usually, this idiom has a negative connotation. If someone gets a free ride, people feel that person has an opportunity or advantage without having done anything to deserve it.

Explain that Free Ride is an artwork by Frank Shebageget. Shebageget is an Ojibway Anishinaabe artist originally from Northwestern Ontario (Treaty 3 territory). Free Ride is a framed collection of fifty $5 bank notes recording Shebageget’s fifty years of annual Treaty annuities.

Under the terms of Treaty 3, Canada promised to provide the Ojibway with various monetary awards—including a one-time cash payment of $12 per family of five and a yearly payment of $5 per person—in exchange for the use of their lands. Many aspects of Treaty 3 remain in contention, including inconsistencies between verbal and written Treaty terms.

Ask the students:

- What do you think the artist is trying to communicate?

- He is trying to dispel myths and stereotypes about First Nations, such as the incorrect notion that Indigenous Peoples get a free ride from the government because of their Treaty benefits.

- By showing a series of $5 bills representing each year of his life, Shebageget is illustrating his ongoing relationship with the government through Treaty 3.

You can read an interview with Shebageget about his artwork in the Bank of Canada Museum’s blog post “Treaties, Money and Art.”

5.3 Discussion

Ask students:

- How does Free Ride help you understand Treaty relationships?

- How can art and artifacts help us better understand historical perspectives?

- What actions can you take to better understand Treaty relationships and your role as a Treaty person?

Extensions

- Draw or digitally design an infographic that summarizes and compares Métis scrip and the Numbered Treaties. How are they “two sides of the same coin”?

- Create an artwork inspired by what you have learned about treaties and the phrase “We are all Treaty People.”

- Use historical thinking to examine bank notes with the Museum’s lesson plans “The Changing Face of Our Money” and “A Bank-noteable Canadian.”

- Learn about objects that were used as money in the past with the Museum’s lesson plan “Money: Past, present and future.”

About the author

Connie Wyatt Anderson is Treaty Education Lead at the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba and a long-time educator from The Pas, Manitoba. She has been involved in creating student learning materials and curricula at the provincial, national and international levels. She has also contributed to a number of textbooks, teacher support guides and school publications. She co-authored the Grade 11 Canadian history textbook used in Manitoba schools and has written for The Globe and Mail, Canada’s History, Canadian Geographic and The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Connie was the instructional designer of Manitoba’s Treaty Education Initiative and continues to train the province’s teachers and school leaders. She has received several awards, including the 2014 Governor General’s Award for Excellence in Teaching Canadian History and the 2017 Manitoba Métis Federation’s Distinguished Leader in Education.

We want to hear from you

Comment or suggestion? Fill out this form.

Questions? Send us an email.