One engraver’s career high

Millions of Scenes of Canada $100 bills are still in circulation, but few of us ever see one. Which is a pity, because it is an example of great bank note design with even greater imagery by a master engraver.

The master

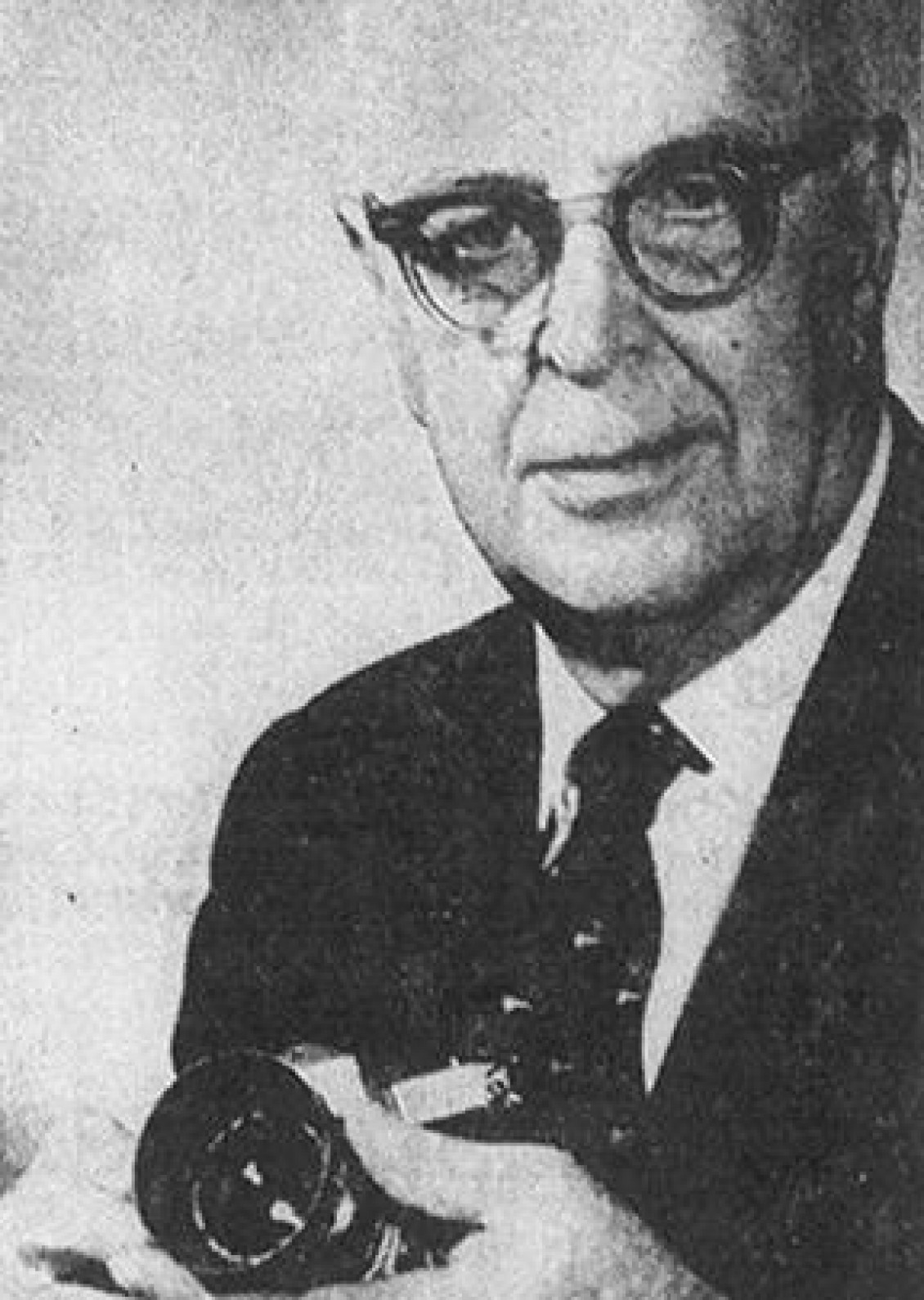

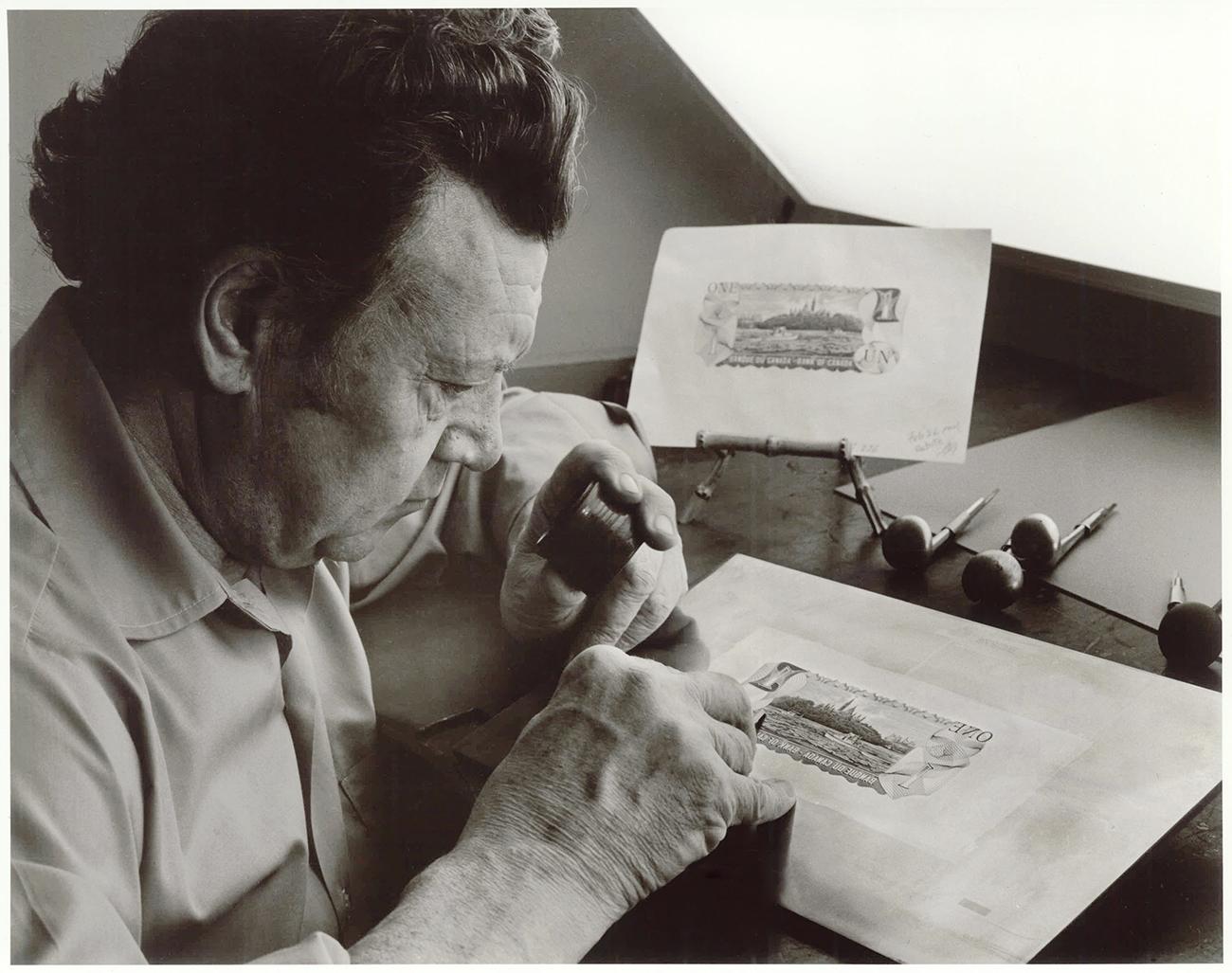

Yorke at work on the Scenes of Canada $1 note. He was described as “…a sensitive, thoughtful person who was neither arrogant nor aloof despite his formidable talents.” (James Haxby, former Assistant Curator, the National Currency Collection)

Source: photo, Malak of Ottawa, Canada, 1973

Charles Gordon Yorke was among the most prolific engravers of Canadian bank notes. Born in 1917, he grew up in Shellbrook, Saskatchewan, a farming village west of Prince Albert. Always interested in art, he travelled to Toronto at the beginning of the Great Depression to attend the Ontario College of Art. He built an impressive portfolio and was hired by the British American Bank Note Company (BABN) in 1935. There, he apprenticed under master engraver Harry Preston Dawson alongside fellow apprentice George Gundersen (who engraved three of the portraits and part of one of the vignettes in the Scenes of Canada series). Yorke remained at BABN for the rest of his career and would engrave an exceptional number of bank notes and a fair number of stamps—along with one character most Canadians will find very familiar.

Engravers sometimes work on each other’s projects or make changes to much older engravings. Among this sampling of Yorke’s work is the 1967 $1 bill, which is an upgrade from a 19th century engraving. The fishing boat vignette on the Scenes of Canada $5 bank note was started by George Gundersen and completed by Yorke.

C. Gordon Yorke’s legacy is the Canadian visual identity he left behind on bank notes and stamps. But to some Canadians, his most familiar engraving is Sandy McTire, the cheery Scottish chap on Canadian Tire money. First appearing in 1961, Sandy remains part of Canadian popular culture even today. However, Sandy’s days are numbered; the coupon program was replaced by a digital loyalty card introduced in 2012. Still, 60 years is a long, long time for any security engraving to remain in the public eye.

The view

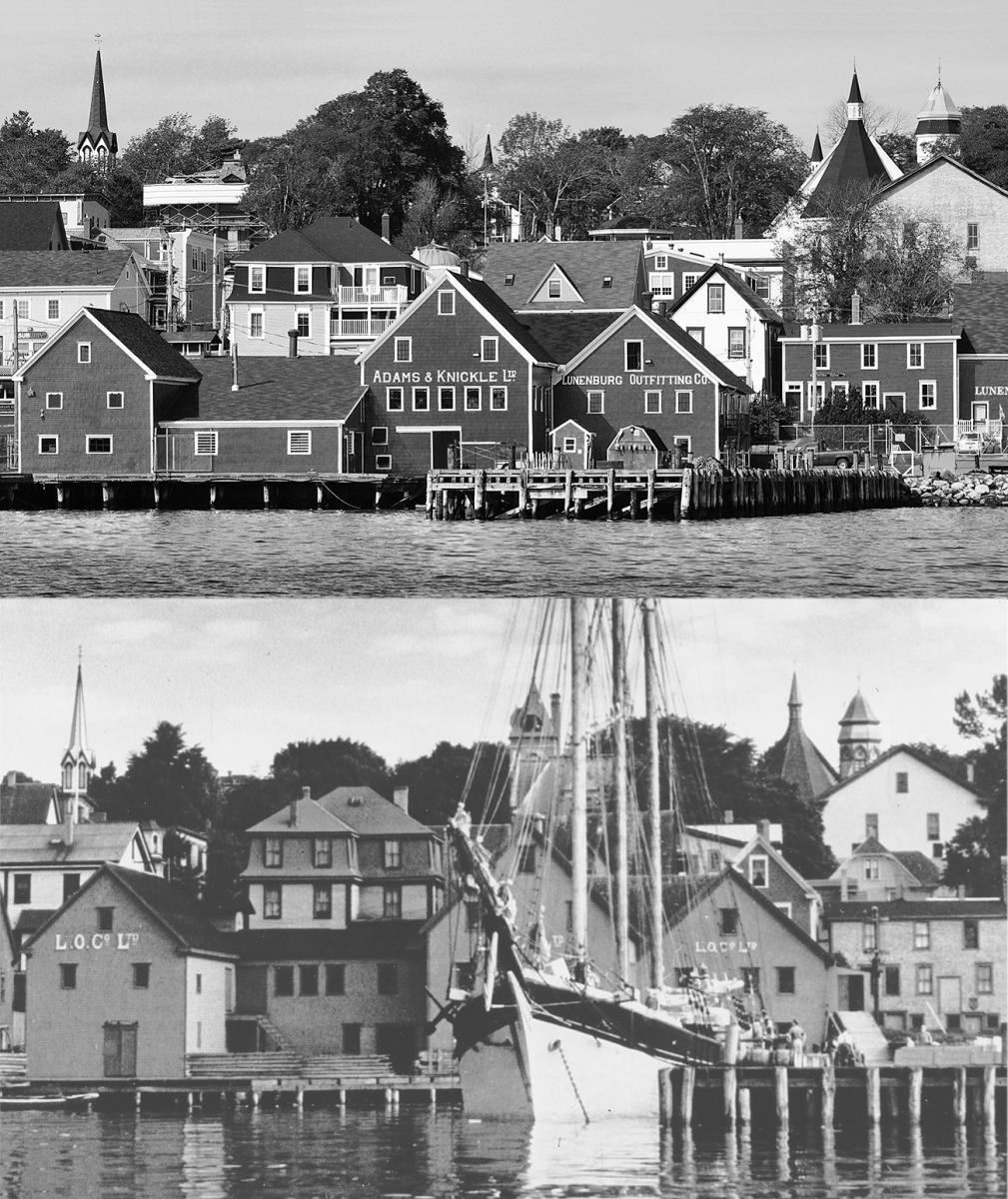

The Mi’kmaq inhabitants called it Aseedĭk or E'se'katik: clam-land. The Acadians called it Mirliguèche, a French spelling of a Mi’kmaq word meaning whitecaps that top the waves in the harbour. The town we now know as Lunenburg is the result of an early effort by Great Britain to create a Protestant settlement in Nova Scotia. In 1753, the British recruited 1,400 people, mostly Germans, to settle the townsite, establishing a Protestant community in territory formerly colonized by French Catholics. It was named after the Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg—the future King George II of England.

Lunenburg is a planned townsite, and the old town has kept much of its original layout and appearance, including many early wooden buildings. Though now a site for cafés and shops as much as for industry, the harbour has remained amazingly intact. In 1995, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated Lunenburg as a World Heritage Site.

The photograph

G. Hedley Doty was one of several photographers who worked for the Nova Scotia Information Service, established in 1924 to promote the province. He was most active from the late 1930s through the 1950s, photographing events, tourism, government, industry, landscape and infrastructure around Nova Scotia. His images are part of what is now a valuable historical archive.

Doty and his colleagues frequently photographed Lunenburg, highlighting the traditional fishing and shipbuilding industries of the era. But it was a time of transition. By the time Doty made the photograph used for the back of the $100 bill in 1939, motor vessels were replacing schooners in Lunenburg’s fishing fleet. Today, Lunenburg still has a fishery, boatyards and a fish packing plant, but a large part of its economy comes from tourism.

The schooner

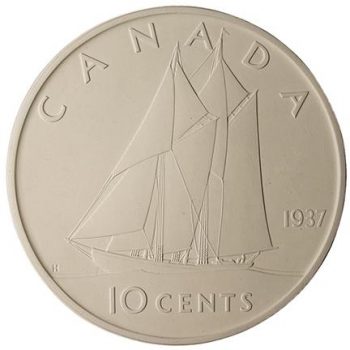

The ships you see on the back of the $100 bill are, from left to right, the Lilla B. Boutilier, the E.P. Thériault and the Theresa O’Connor. The two on the outside appear to be traditional Grand Banks schooners. Hundreds of these sleek and exceptionally fast little ships worked the fishing banks off the coast of Nova Scotia from the mid-19th century. The most famous example of a Grand Banks schooner is the Bluenose. Proudly built in Lunenburg, it was designed to race—specifically to challenge American schooners for the Fisherman’s Trophy. It lost only one race in its career and once held the record for the biggest catch of fish brought into Lunenburg.

When Doty was photographing Lunenburg, fishing schooners were beginning to disappear. By the time the bank note was issued, only a handful were still working the Atlantic coast and the Caribbean, mostly as cargo or tourist vessels. But these ships are such a symbol of pride for Nova Scotians—and so iconic of a whole way of life—that one has been sailing on our dime since 1937.

The vignette

Like every bank note ever issued by the Bank of Canada, the Scenes of Canada $100 bill went through numerous minor and major iterations. Two versions of the note can be found among the printing proofs, models and plates in our collection. An early, less elegant version shows an image without the schooner on the far right.

As well as the cropping of the image, the guilloche patterns (the intricate and detailed decorative patterns) and letter forms are substantially different in these designs. The bottom one is nearly final.

Source: 100 dollars, back model, Canada, 1972 | NCC 1993.56.629; 100 dollars, print proof, Canada, 1975 | NCC 1993.56.643

Yorke’s final reference photo is actually a collage that mixes the visual elements from differently sized prints, dropping the height of the ships’ masts and the buildings to better suit the wide frame of the note. Trees were also added along the horizon—perhaps to better separate the buildings and sky.

Source: photo, British American Bank Note Company, 1972 | NCC 1993.56.624

As working fishing vessels, the Grand Banks schooners had passed into history when Yorke sat down to engrave the Scenes of Canada $100 bank note. Yet, a fascination with these ships and the people who crewed them still endures—as it has since before the heyday of the Bluenose. And Lunenburg is as popular and romantic as the ships that helped make it famous. Being on a $100 bill didn’t hurt either.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.

Treaties, money and art

The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art?