The dollars and cents we use wouldn’t be worth anything to anybody if we didn’t have confidence in it. No matter if it’s gold or digits on a hard drive, public trust is the secret ingredient in a successful currency.

Trust is the raw material from which all types of money are minted."

Yuval Noah Harari, ???????

Trust in precious metal

In ancient times, trust in coins was generated by the type and quality of metal they were made of, and the consistency of their weight. It was also the familiarity of the shape and look that helped seal the trust deal on a coin.

Currency minted under the reign of Alexander the Great of Macedonia (Greece: 356 BCE to 323 BCE) was trusted long after he died, accepted by merchants from Thrace to Alexandria and beyond. Some of the rulers who took over Alexander’s former empire kept his image on their coins, hitching a ride on the population’s existing familiarity with Alexandrian coins. They fulfilled the expectations people had for a coin to be certain weight and made of the right stuff. Simply put, they looked like money.

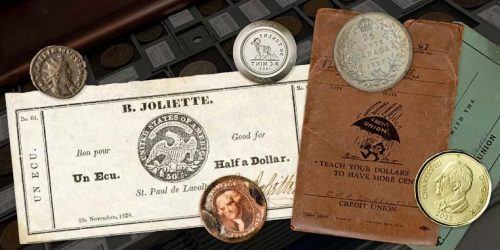

Trust is inherited

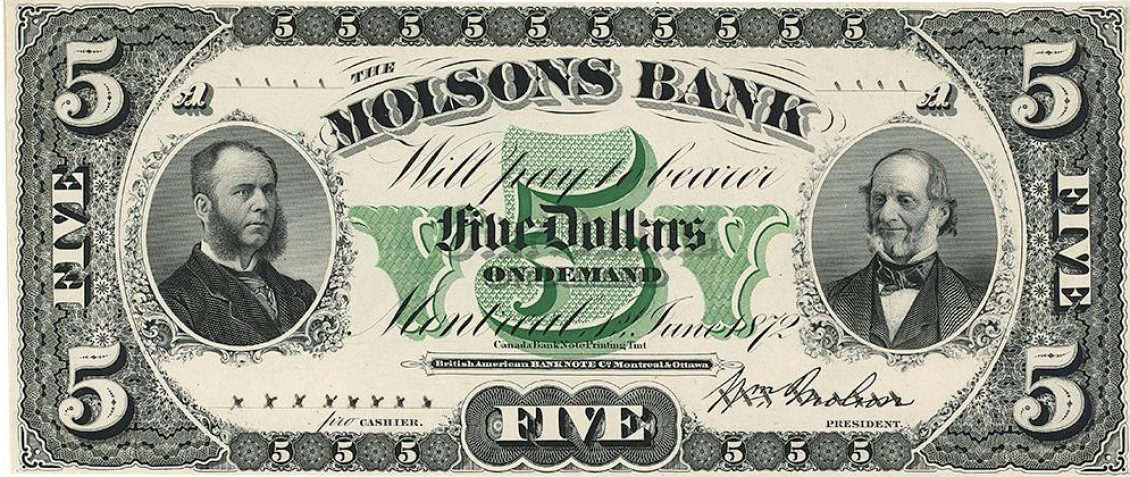

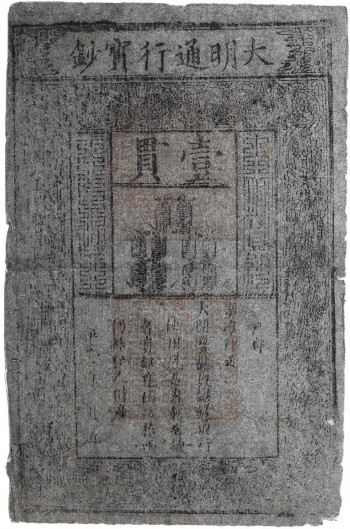

Although many currency forms and trading practices exist simultaneously, there is a general evolution traceable from ancient coins to the money we use today. But it happened in baby steps. In medieval Europe, trust was still largely attached to the intrinsic value of a currency—its value as a metal. So, if you’d offered to pay a merchant in 16th century England with paper money, he’d have thought you were nuts. The first functional paper currencies didn’t appear there until the 17th century and were essentially receipts that represented an amount of gold in a goldsmith’s vault. Early paper money inherited its trust from both the metal it represented and the authority who issued it. But for those of the public who regularly used money, a paper version required a pretty serious leap of faith.

Paper money: the great leap of faith

Some paper money officially represented precious metal well into the middle of the 20th century. It was part of an economic system known as the gold standard, and every country using that system had a stockpile of gold to back its currency. Theoretically, people could exchange their bank notes for gold coins at any time, though it’s questionable how many actually did. Good thing, too, because banks and governments regularly issued more paper money than there was gold to back it. After 1913, the US Federal Reserve was only required to have enough gold to back a mere 40% of its bank notes. There wasn’t enough gold in the ground to meet the needs of growing economies, anyway. This attachment to gold reserves tended to strangle economic growth and was an especially serious problem during times of war.

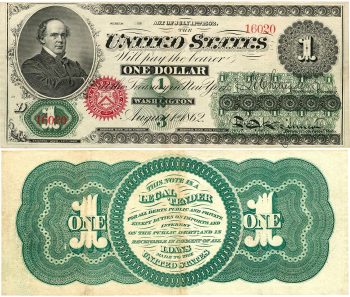

To help fund the American Civil War (1861–65), Abraham Lincoln’s government created a plan to suspend the gold standard and print unbacked money. These notes, called “legal tender,” were put into circulation in 1862. And the plan succeeded. Americans had been using paper money in one form or another for a few generations and had learned to trust it. How—or if—the money was backed no longer seemed as important so long as it was issued by a respected authority. The trust in gold reserves was safely transferred to the issuing authority.

Legal tender (or fiat money) is what every one of us uses today.

In 1862, legal tender money was so new that “greenbacks” came with instructions printed on them noting what sort of debts and obligations they could be used for.

Source: 1 dollar, United States, 1862 | NCC 1966.98.2424

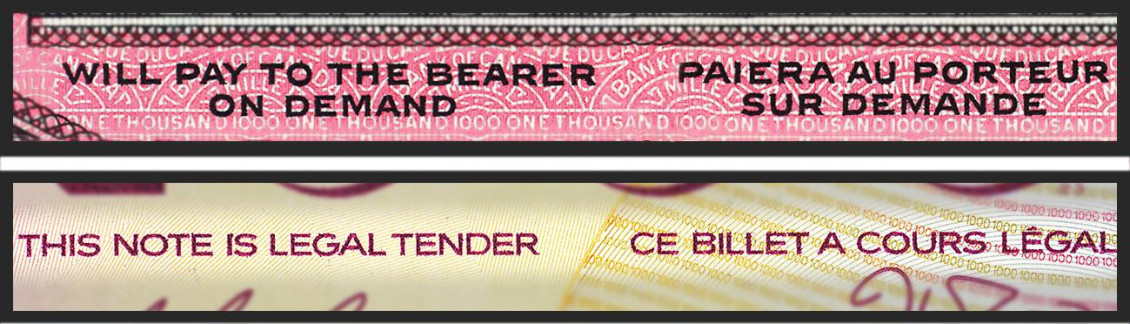

“Will pay to the bearer on demand” means you can exchange your bank note for its value in gold coins. Though this phrase remained on all our bank notes until the late 60s, Canadians haven’t been able to convert their notes to gold or silver since 1929.

Source: 1,000 dollars Canada, 1986/1,000 dollars, Canada, 1954 | NCC 1992.11.22 | NCC 1973.175.2

Modern money is just a number—supported by trust

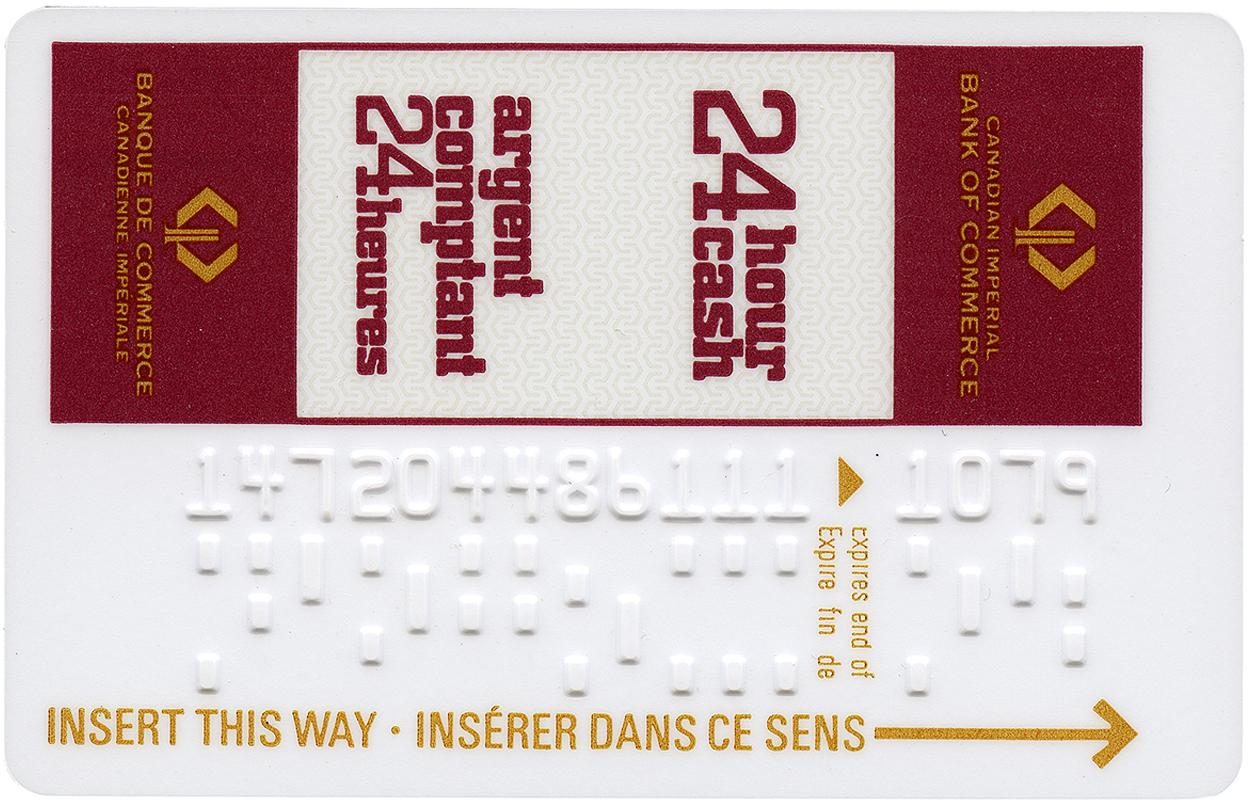

Ever since banks began, people’s savings have been just a few numbers written in a ledger—their share of the bank’s total holdings. And today, those holdings are no longer precious metal—or even cash. To be clear, banks still have cash on hand, but it’s merely one of several delivery systems for the numbers in their databases. Cash has really become a service that banks provide for those who don’t use payment cards or e-transfers.

But even the electronic transfer of money evolved in baby steps. Electronic payments hark back to the 1870s when you could “wire” money via Western Union’s telegraph system. And credit cards were around for a generation before debit cards. We’ve gotten used to the notion of invisible money, now. We trust it. Or more to the point, we trust the electronic financial system.

Remember the future?

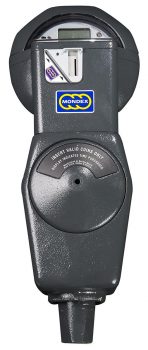

But some invisible money really was ahead of its time. In 1997, a company called Mondex tested a digital money transfer system in Guelph, Ontario, and Sherbrooke, Quebec. At that time, even debit cards were just beginning to gain acceptance, and Mondex was a big leap forward into true e-money.

You loaded a Mondex card with funds from your bank. You could then transfer the money to stores or parking meters or payphones—and even between users. The money existed in digital form and only on your smart card.

But sadly, most people gave Mondex a miss. At that time, digital payments of any kind were in their infancy, and there simply wasn’t widespread trust in such technology. There were also fears of losing the card. But today, trust in technology has matured. We seem to be ready and willing to accept any number of electronic payment systems, e-monies or even cryptocurrencies.

In technology we trust

The Bank of Canada, along with central banks all over the world, is researching a national digital currency. It has no plans to issue one in the foreseeable future, but nonetheless wants to be prepared. A central bank digital currency (CBDC) would be a digital version of our currency—a digital loonie. It would maintain stable value, be universally acceptable and transfer easily.

A digital currency’s time may be on its way. Just add trust.

Read more about e-money and CBDC research on the Bank’s website

Central bank digital currency (CBDC)

Contingency planning for a central bank digital currency

S. Murchison, “The road to digital money,” Bank of Canada The Economy, Plain and Simple

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.

Treaties, money and art

The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art?