The Scenes of Canada one-dollar bill

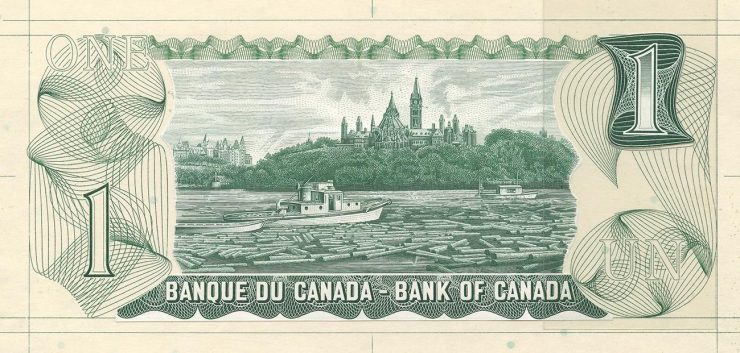

Thanks to a bank note, an image of a river of logs floating past Parliament Hill has long lived in Canadian collective memory. Though beautiful and evocative, the image is actually showing an accident.

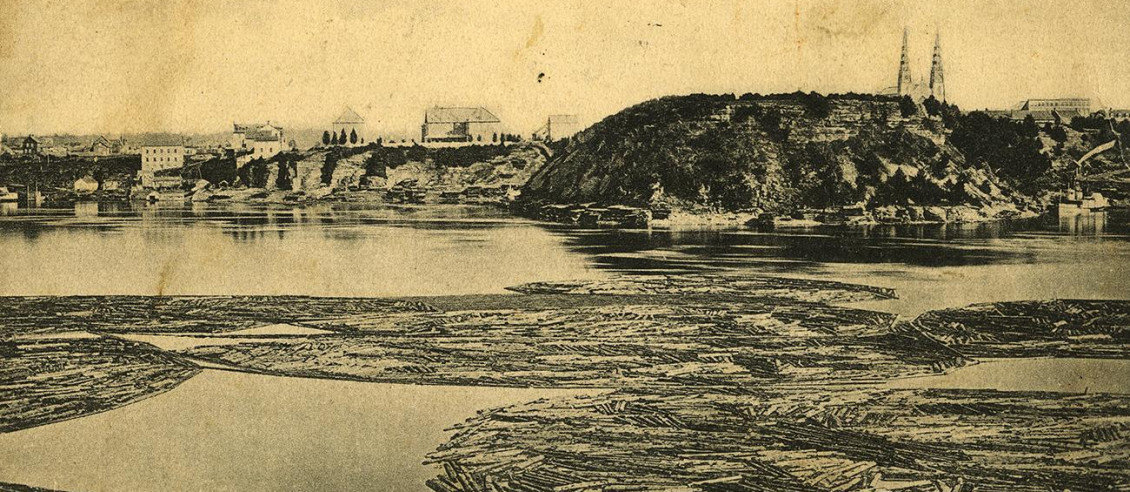

Eastern Ontario’s timber highway

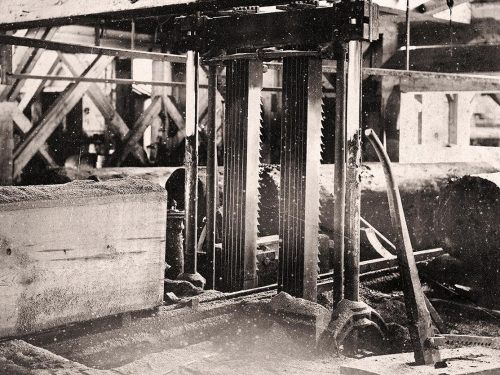

Logging has long been an iconic Canadian industry, one of Canada’s founding economic building blocks. And part of its birth originated with an aggressively ambitious fellow named Napoleon Bonaparte. When Napoleon’s advances across Europe cut England off from its traditional timber sources, it turned to heavily forested British North America to supply the wood it desperately needed. The old-growth eastern white pines of what is now Ontario made ideal masts for the great warships of the era, and the industry quickly expanded, producing lumber of all kinds.

Many lakes and rivers that drained into the Ottawa River became the secondary highways of the industry. Millions of logs were floated downstream to the Ottawa, en route to the St. Lawrence River and the dock yards of Montréal and Québec.

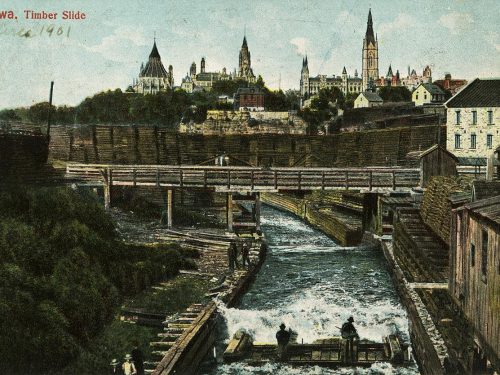

On the Ottawa, timber was contained inside booms, huge loops of logs chained together. At waterfalls and rapids, man-made channels called slides allowed the logs to bypass these natural barriers. Ottawa’s Chaudière Falls—sacred to the Anishinaabe people and called “Akikpautik”—presented just such a barrier. A booming lumber industry sprung up on the nearby shores and islands of Hull (Gatineau) in Quebec and Bytown (Ottawa) in Ontario. Mills drew their power from the movement of the mighty river, and the beautiful Chaudière Falls were corralled to provide hydroelectricity.

The industry that made a capital

Before the government claimed it, Ottawa was a lumber town.

The lumber barons who gave Ottawa and Gatineau such street names as Bronson, Wright, Booth, Maclaren, Gilmour and Eddy laid the economic foundations of Ottawa. They built sawmills and railways, owned fleets of river boats and employed tens of thousands of labourers. But the timber boom in eastern Canada was already tapering off by the turn of the 20th century.

The sawmills and lumber yards remained features of Ottawa and Hull for another generation until replaced by the pulp and paper industry. The last pulp log booms passed Parliament Hill in the early 1990s. Today, there is only one functioning mill in this once bustling industrial hub. Far from cutting lumber out of mighty white pines, it manufactures paper towels and tissues.

The beautiful mishap

On a sunny summer day in 1963, Aldomat Legault was piloting a small tugboat, the Missinaibi, towing a log boom up the Ottawa River to the E.B. Eddy plant. Without warning, the boom broke open and thousands of logs escaped, drifting in the strong current. With help from other boats on the Ottawa that day, Legault was able to gather the logs back together and finish his delivery. “It’s not often you see that kind of break,” recalled Legault in an interview with the Ottawa Citizen. “It was quite a sight right in front of the Parliament Buildings.”

When the boom broke, photographer Malak Karsh happened to be at the E.B. Eddy plant on the Hull shore. He was on assignment for the Canadian Pulp and Paper Association. Attracted by the amazing sight of a river full of logs, he stepped aboard another tugboat and took what became one of his most famous images. Malak Karsh was a noted photographer who worked in the Ottawa area on commercial and industrial assignments. And yes, famous portrait photographer Yousef Karsh was his big brother.

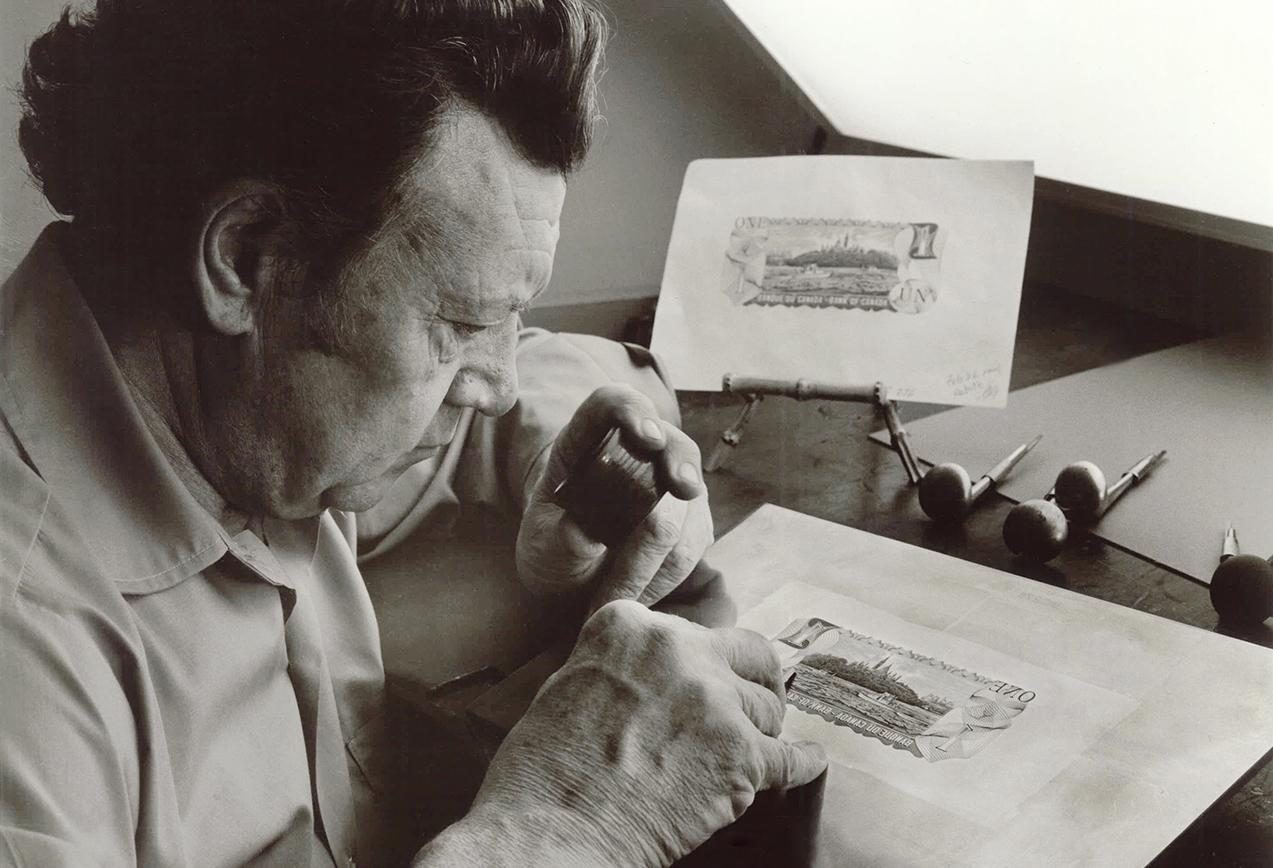

The engraving

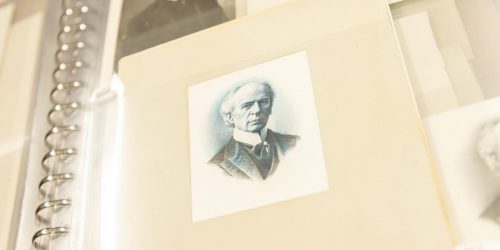

C. Gordon Yorke was the talented engraver who created the back vignettes for the $1, $2, $5 and $100 bank notes of this series. He also engraved the portraits of Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Sir Robert Borden.

Source: Photograph by Malak of Ottawa, 1973

The image on the back of the Scenes of Canada one-dollar bill is very well suited to the general theme of the series. It is a landscape with human activity, sweetened with a dash of the sentimental.

Engraver C. Gordon Yorke took some liberties with the image, reducing the number of logs in the scene to simplify the visual chaos. Curiously, he removed the men from the decks of both tugboats. There is no clear reason why, as he included all the men in the fishing boat on the $5 bill. He also added a flag to the Peace Tower. There was no flag flying from the Peace Tower at that moment, a highly unusual occurrence.

The boats on the bill

The Missinaibi is an 11-metre, steel-hulled tugboat designed and built for the lumber trade by the Russel-Hipwell Engine Co. of Owen Sound, Ontario. The Missinaibi was launched in 1952. Retired from log driving about the time our bank note was issued, the old tug sat in a Gatineau boat yard for 10 years until it was restored by the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now called the Canadian Museum of History) and placed on the riverbank behind the museum.

In the background of the engraving is a smaller tugboat, the Ancaster, also built by Russel-Hipwell. In 1979, it sank near the Chaudière Falls dam. Ontario Hydro raised the vessel and, with an enthusiastic crew of hydro workers, restored it. It is now on display at the Owen Sound Marine and Rail Museum.

Like the BCP45, the fishing boat on the $5 bill of this series, these boats undoubtedly owe their preservation to their appearance on a bank note. The little tugs are two of the few remaining physical links to the industrial heritage of the Ottawa region, industry that helped define much of the nation and its economy.

A final note

The last sheet of Scenes of Canada $1 bills rolled off the press on April 20, 1989. They were also the last $1 bank notes the Bank of Canada issued. By then Canadians had been getting used to the loonie ($1 coin) for nearly two years, and in 1996, the $2 bill would also be replaced by a coin.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.

Treaties, money and art

The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art?