Or, why superheroes shouldn’t tile their own kitchens

More than 30 percent of Canadian homeowners spent at least $5,000 on home renovations in 2019. And many did so as DIY (do-it-yourself) projects. Was it the best use of their time? How about DIY on a national scale?

Peter Parker’s shabby apartment

Some people’s time might be worth too much to spend on home renovation.

Let’s imagine for a moment that Spider-Man, in his everyday Peter Parker format, has scraped together enough money to buy himself an apartment. He lives in New York, so that’s not easy—even for a superhero. Chances are the place would need some work. With his “Spidey” powers, Peter would no doubt do a fabulous job tiling the kitchen backsplash.

But while our hero chews on a pizza slice waiting for his grout to set, the Green Goblin and Doctor Octopus are out there wreaking havoc on the good citizens of New York. It’s time for Peter to pull on his red and blue onesie and get moving! It’s also time to call in the contractor.

Peter Parker may be far from wealthy, but losing the chance to save some money by doing his own home renos is worth it to him and his reputation. Giving up those savings is similar to what economists call an “opportunity cost”: a benefit that a person or a business gives up to take advantage of another—hopefully better—opportunity. And the results of similar choices can be seen in a nation’s economy.

Do-it-yourself nation

In the two decades before the First World War, hundreds of automobile makers popped up all over the Western World, Russia and Japan—and disappeared nearly as quickly. In that era, automobile manufacturing was still a localized, cottage industry. Shipping cars was expensive, so it would seem to have made sense to purchase a locally produced vehicle (even if it couldn’t climb a hill to save its life!). But even the cheapest local vehicles would have been too expensive for the vast majority of people.

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy..."

— Adam Smith, economist, An Inquiry into the

Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776

Economies of scale soon took over the industry. The lion’s share of hand-built automobiles gave way to an assembly-line car—affordable to far more people. Importing cars from more efficient builders—such as the Detroit giant, Ford—was a more practical proposition for a nation than building home-grown products. In other words, importing foreign cars was worth the opportunity cost of giving up locally producing them. But, of course, the market gave them little choice.

After the war, Model T Fords began to dominate auto markets from Algiers to Zambia. Ford had what is called an “absolute advantage” in manufacturing automobiles. It could supply a reliable car more affordably than other nations’ companies could. For many countries, it was therefore more profitable to import Fords and divert their workforces to what they did best—be it mining nickel or weaving cotton. And this production shift is a big part of what is called “comparative advantage,” a concept created by 19th-century theoretical economist, David Ricardo. His theories were, in turn, based on those of 18th-century economist Adam Smith, a major figure in economic history. Comparative advantage is a cornerstone of modern thinking about free trade.

David Ricardo and fine British wine

David Ricardo is considered one of the greatest theoretical economists. Amazingly, Ricardo’s ideas about free trade were not based on personal observations of a functioning economy. But his theories were so perceptive and mathematically sound that they still resonate today. Comparative advantage was his most long-reaching theory. Subtle and complicated, it seems at first glance to defy common sense.

. . . a country may, in return for manufactured commodities, import corn even if it can be grown with less labour than in the country from which it is imported."

— David Ricardo, Principles of Political

Economy and Taxation, 1817

Ricardo reasoned that in a free international market, the economic advantage of a country manufacturing a product did not necessarily lie in how cheaply it could do so. What had to be factored in was what economic advantages the country had to give up to produce more of that product: the opportunity cost. You still with me? No? Here’s an example that’ll help.

Ricardo sketched out a scenario in which England and Portugal produced only two items—cloth and wine:

- England produced 2,000 units of wine and 4,000 units of cloth.

- Portugal produced 4,000 units of wine and 6,000 units of cloth.

- All together, 6,000 units of wine and 10,000 units of cloth were produced for the market.

There would seem to be no point in Portugal importing anything from inefficient old England, would there?

But, if you look at each country’s opportunity cost of producing wine, everything changes. Basically, a less efficient country can profit from free trade not by capitalizing on its best advantages, but by moving the bulk of its production to where it has less of a disadvantage. OK, that’s not much help, so let’s look at the numbers:

- Since England’s workforce can produce half as much wine as it does cloth, it loses the potential of making two units of cloth every time it makes one unit of wine: this is England’s opportunity cost of wine production.

- Since Portugal’s workforce can produce 50 percent more cloth than wine, it loses one-and-a-half potential units of wine every time it makes a unit of cloth: this is Portugal’s opportunity cost of cloth production.

So, given these opportunity costs:

- If England diverted one-half of its wine workforce to making cloth, production would jump from 4,000 units to 8,000 units of cloth.

- If Portugal diverted one-half of its cloth workforce to making wine, production would jump from 6,000 units to 8,500 units of wine.

All together, more of each product is produced for the international market: 9,500 units of wine and 11,000 units of cloth. England’s surplus cloth can be exported to Portugal and the surplus Portuguese wine to England. Everybody wins.

And if Spider-Man really likes grouting tile?

That might seem a little odd, but there certainly is satisfaction in building something yourself, no matter how lumpy and lopsided the result. Besides, why pay somebody to do something you can do yourself, right? Sure, but this makes little economic sense on a national scale.

People might feel proud of, say, a home-grown supersonic jet fighter. But in the end, the enormous human and physical resources needed makes it far more economically sensible to leave building fighter jets to the professionals of other nations. This frees up the workforce to shift to a more cost-effective sector—perhaps producing products that can be exported to the jet-building nation.

Every country has different zones of economic production, and so does the planet: places best for building cars (or car parts), places best for producing maple syrup. Maybe there’s a place that best produces superheroes, heroes who will hire some normal folks to paint their bathrooms or insulate their attics. Then they can get on with the task of saving us all from the villains and evil geniuses.

For more detailed information, have a look at the Bank’s The Economy Plain and Simple article on free trade and watch the video on comparative advantage.

The Museum Blog

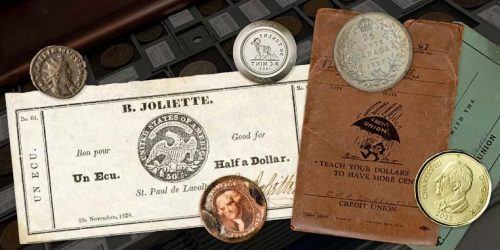

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.

Treaties, money and art

The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art?