The curious system of old British money

For daily users of modern money, getting an understanding of the old British system of currency can be an act of confusion and wonder. But it’s also a peep into 13 centuries of European numismatic history.

A beautiful heap of 13 denominations covering 700 years of the British economy, from King Edward III to Queen Elizabeth II.

A great idea

Historians probably disagree on what made Russian Tsar Peter the Great great. But for numismatists, it was likely his 1704 introduction of a decimal currency—one like ours, with a base unit divisible by 100. When he adopted decimal currency, he really did his people a favour: he freed them from the mathematical tyranny of the old Carolingian currency system, one with a base unit divisible by 240! A thousand years old by then, that system was not abandoned by the United Kingdom until 1971.

Old English money has its roots in old French money

The first king of the Frankish Carolingian Dynasty, Pepin the Short, reformed his currency around 755. His new, Carolingian system was based on a silver coin, 240 of which could be minted from a pound of silver. Back then, a pound was lighter than it is today, being composed of 12 “troy” ounces. Today’s pound is 16 ounces, but a troy ounce is 3 grams heavier than a modern ounce. To this day, silver and gold are measured in troy ounces.

Pepin’s son Charlemagne expanded the Frankish empire, spreading this currency system over much of Europe. The Saxon kings of England adopted the Carolingian system in the late eighth century, issuing silver pennies of the same weight as the Frankish denier. While this simplified European trade, it also doomed English money to be increasingly confounding—though charmingly eccentric—for the next 1,200 years.

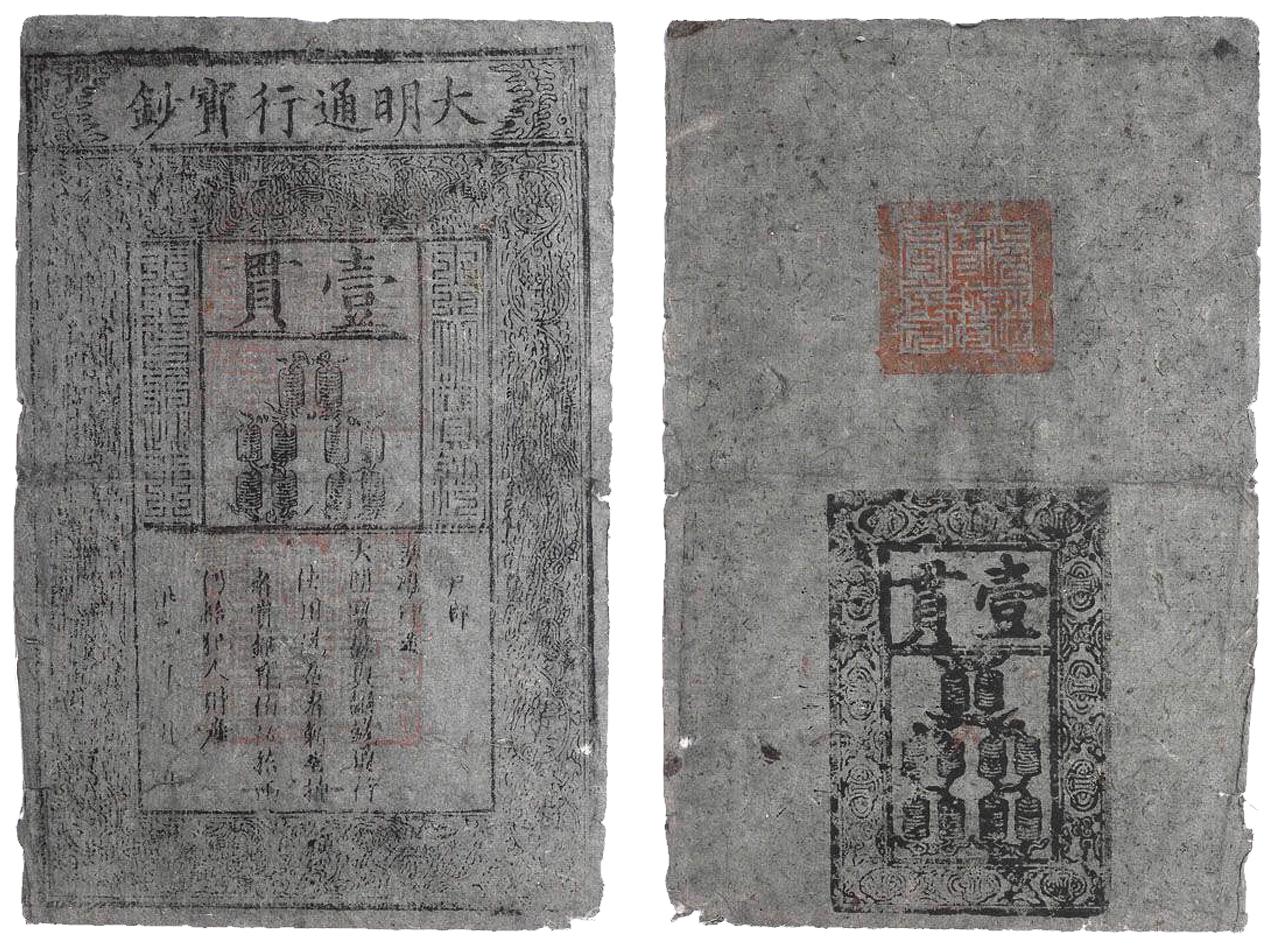

A medieval penny was nothing to sneeze at

The penny hasn’t always been a low-budget coin. For many hundreds of years, a penny was a coin of solid silver with real buying power.

According to some historic sources, in Anglo-Saxon England, you might have taken home 15 chickens for a penny. If you were feeling rich, four pennies could have bought you a “hive swarm after August.” Wow! Used bees aside, many things would have cost far less than a penny.

So, just like today, the British economy required a variety of denominations.

The revenge of the Romans?

The history of the British peoples is an accumulation of conquerors’ influences, and Roman coins were the currency of England for more than 400 years. The Romans left their mark in the seemingly nonsensical symbols of British denominations. The age-old plural form of penny is “pence.” And its symbol is “d.” D?! It stands for “denarius,” a Roman denomination. The pound is denoted as “£,” which makes a bit more sense when you understand that it is short for the Latin word “libra,” a Roman measure of weight (also seen in our abbreviation for pound: “lb.”). The shilling is denoted as “s.” OK, that seems rational. Nope. It’s short for the Latin denomination of “solidus.”

OK, so what’s with “pound sterling”?

The Anglo-Saxon era ended rather suddenly in 1066 with the successful, if bloody, conquest of England by Prince William of Normandy. Despite the cataclysmic changes he brought to the island, he saw no reason to change the monetary system—it was identical to the French. In that era, the penny began to be known as the “sterling.” And 240 pennies were one pound of sterlings or “one pound sterling.” Sound familiar?

For much of its history, British money was expressed in pounds, shillings and pence. Not to make it at all simple, a shilling was worth 12 pence, and a pound was worth 20 shillings.

Some very curious coins indeed

Surrounding those three basic denominations is a whole slew of coins spread over more than a millennium of regulated coinage. They didn’t all exist at the same time—they came and went to suit the demands of the economy, politics, and the capricious values of precious metals. To make things mildly rational, these denominations could all be expressed in pence or shillings but continued the British numismatic tradition of being awkwardly divisible and a little bit odd.

Most of these denominations were issued in both fractional and multiple forms. At various times, one could pay with a half angel, tuppence (two pence), thruppence (three pence), sixpence, a half-penny, a quarter-guinea, a half-laurel, a half-crown, a double-florin and, best of all, a three-half-pence piece! The currency was also rich in nicknames like “copper,” “ha’penny,” “mag,” “bob,” “tanner” and “quid.”

A monetary system that overstayed its welcome

The perennial drawback of the Carolingian system was the fluctuating value of a pound of silver. The buying power of a coin in your pocket would vary depending upon the market value of the metal it was made from. It even depended upon how worn the coin was. Occasionally, values of precious metals would change too quickly and the currency would need to be reformed. A denomination such as a gold unite would disappear, to be replaced by a coin worth the same value in pence but smaller in size. This currency reform was not unusual for much of Europe’s numismatic history, but very unusual in any economy after the First World War.

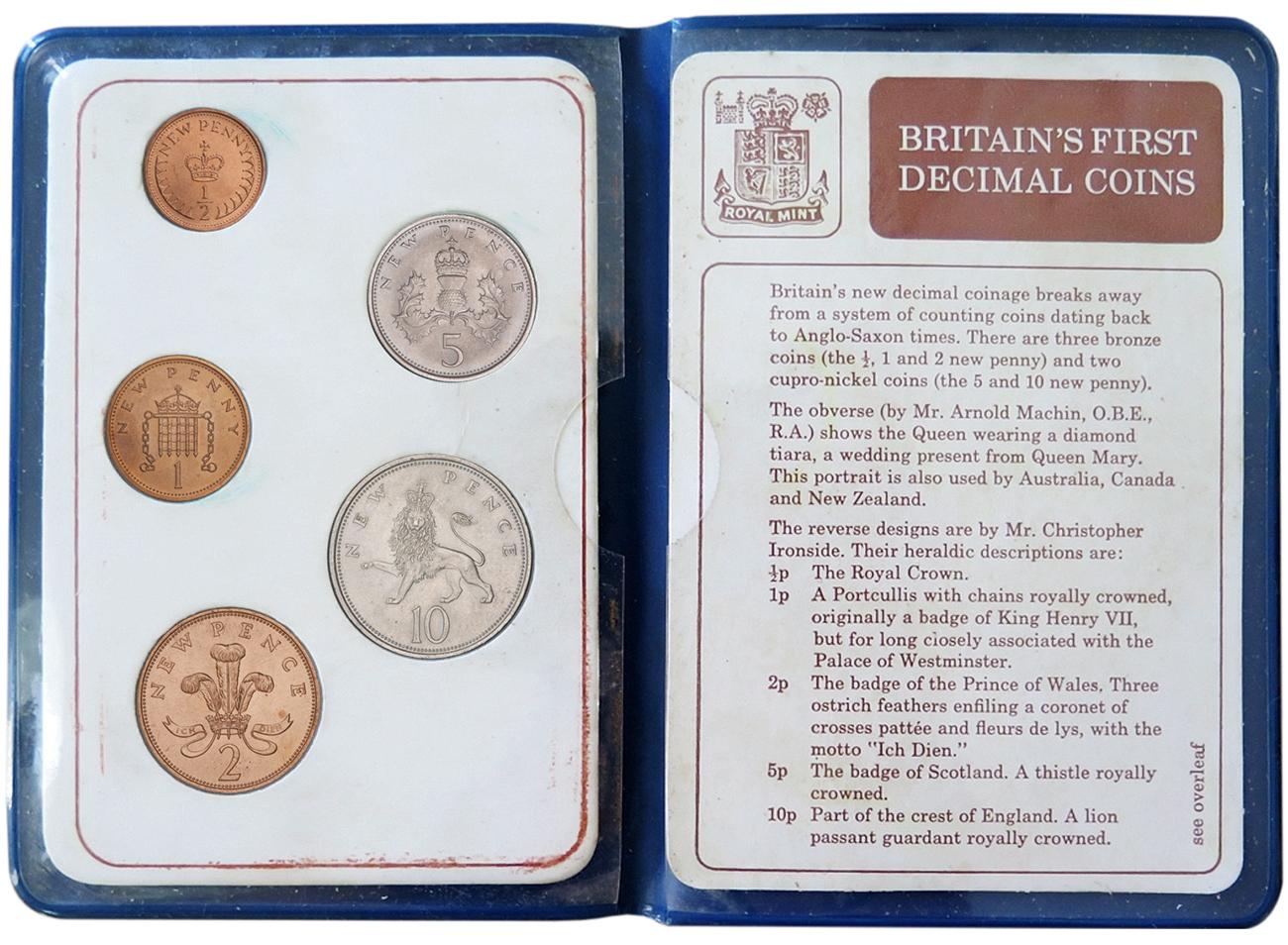

It would all come to a halt on February 15, 1971, the day the United Kingdom officially introduced the decimal coin system into the public economy. For two years, there had been advertising campaigns and most prices were listed in both systems. Still, confusion reigned supreme, as harried merchants had to use decimal currency as change for payments made with the old money system. Shillings, florins and crowns disappeared, giving way to coins based on a pound divided into 100 pence.

Very rational. Very simple. But not nearly so charming.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.