Every culture has nicknames and metaphors for money. They are so widespread that most of us barely notice how often we use them.

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money or a financial situation, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from. Some have surprising backstories, while others are simply well-informed guesses. Many have roots long lost in the ongoing history of English.

The crazy coin?

If you aren’t a Canadian reader, you may be unaware that our dollar coin is called a loonie. But it’s not hard to figure out why, so long as you recognize that the bird on the coin is a loon.

There is no specific event or person credited with coining “loonie.” The nickname seems to have turned up in our speech almost simultaneously with the coins in our pockets. In fact, so fixed is the word loonie in Canadians’ minds that the Royal Canadian Mint copyrighted the term in 2006.

The colour of money

The green stuff, lettuce, cabbage, spinach... Why is paper money so associated with the colour green? It all starts with a war. When the US government of the 1860s needed a new means of financing its efforts in the Civil War, it issued new paper money with the backs printed in a dull green, high-security ink. People called them greenbacks. The name became so popular that the backs of all US notes are still printed in the same colour today.

That’ll cost you a buck(skin?)

One of the most familiar money nicknames in North America also has one of the murkiest backstories. There’s a theory that “buck” is derived from “buckskins.” These were the hides of male deer or antelope. Buckskins were traded in early colonial North America, but they came in all sizes and qualities and had no standard value. Besides, buck didn’t come into common usage until paper money did—well after trading with buckskins had become a thing of the past.

Another theory holds that, during poker games, a knife with a buckhorn handle would be passed from one player to another to indicate who was the next dealer—hence the expression “pass the buck” which means passing on responsibility. The knives were later replaced by silver dollars.

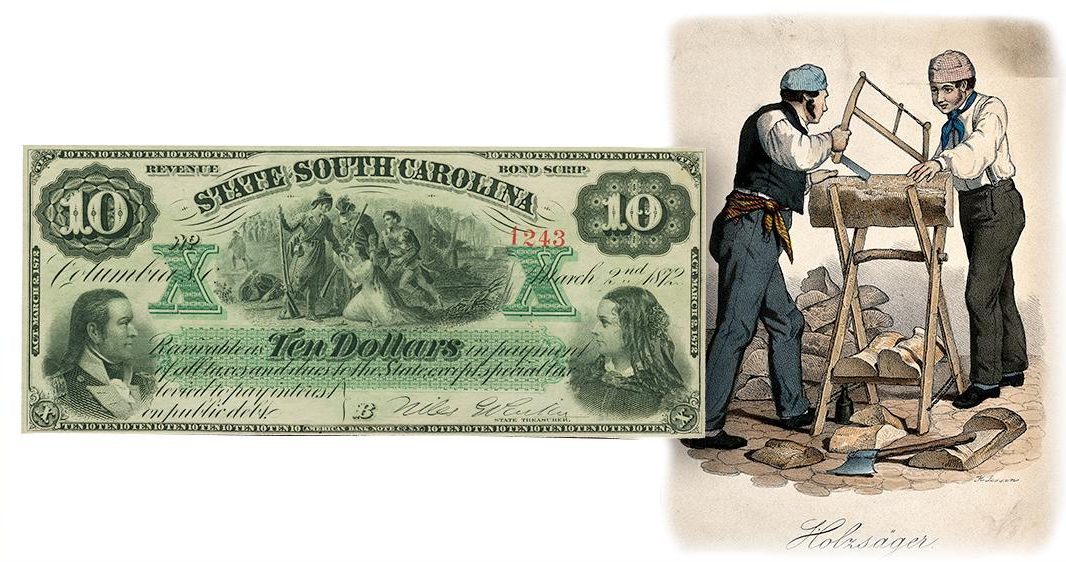

A more likely clue might be found on the bank note above: the sawbuck. Given that the term buck didn’t really come into use until the late 19th century, it makes sense to link it to the already-existing term “sawbuck.” Still, nobody’s at all sure about this.

One coin, two bits

A quarter makes perfect sense to us: it’s one-quarter of a dollar. But two bits? If you have any interest in pirate lore, you’d be familiar with a piece of eight. That’s a big, silver, Spanish eight-reales coin—often called a silver dollar. It was the US greenback of its day and was accepted all over the world. But the coin was too valuable for many purchases. So, to make change, one would simply cut the silver dollar into wedges—usually eight of them. So, what was a quarter of a Spanish dollar? Why, two bits, of course.

A pocket full of mollusks

If somebody said that they just spent 1,000 clams, just from the context you’d probably figure out that a clam means a dollar. How? This nickname may stem from the use of cowrie shells as currency. For thousands of years, these little shells from the Indian Ocean circulated in economies all over the world—even along Indigenous trade routes in North America.

And “shelling out”? That’s spending money—usually too much of it and certainly with great reluctance. The best backstory we could find for this metaphor seems to have nothing to do with mollusks. It may, however, be related to another slang term for coins, “coriander,” used in the 18th century. So, shelling out would refer to digging coriander seeds from their shells—like (reluctantly) digging money from your wallet.

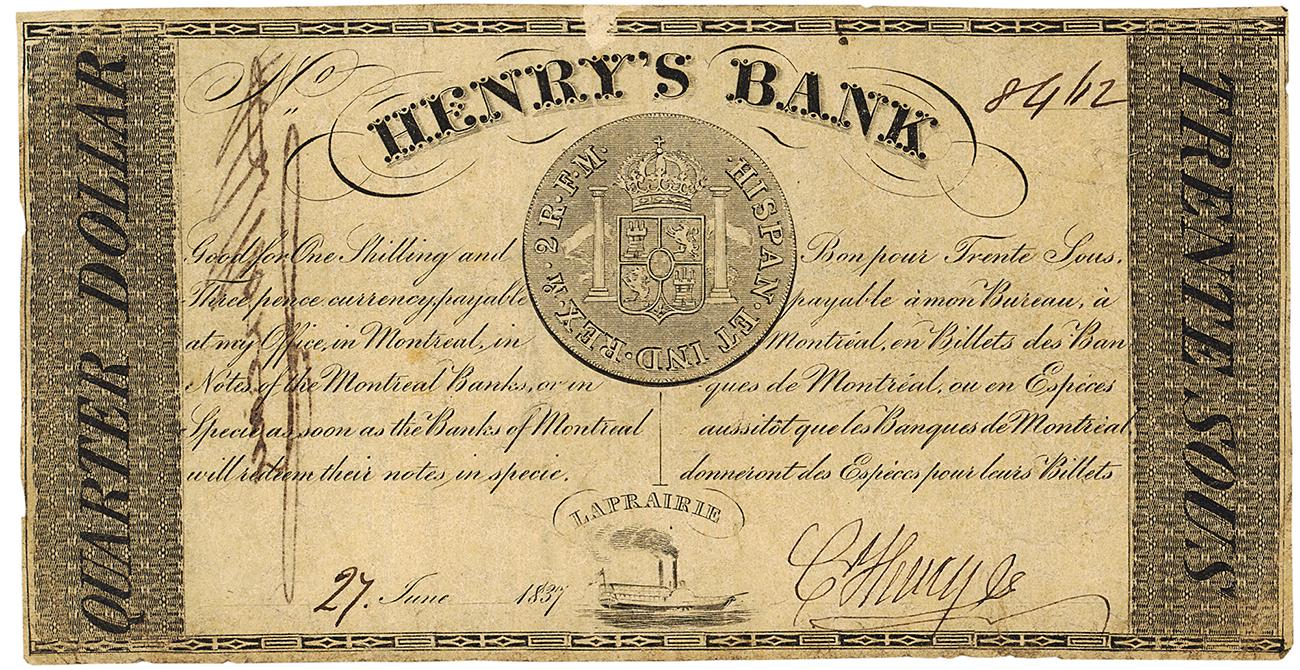

The 30¢ quarter

For generations, French Canadians have referred to a quarter as a “trente-sou.” Literally translated, this means 30 cents. But that doesn’t add up. When the French regime gave way to the British in 18th century Canada, an English pound was valued at 120 French sous. A quarter of a pound was, therefore, 30 sous. After the decimal system came about in the mid-19th century, the term was applied to a quarter dollar, and trente-sou is still heard among French Canadians today.

Hard-boiled cash

For the most colourful money metaphors in the English language (or any metaphor, for that matter), look no further than American hard-boiled detective fiction from the first half of the 20th century. You’re likely familiar with the genre: stories about tough, cynical private investigators, loners who make their own rules and aren’t strangers to whiskey, fist fights, side arms and doing the occasional overnighter in police custody.

For your entertainment, and education, check out this list we’ve put together of financial terms from the genre.

- stake—savings intended to be gambled (also: poke)

- bookie—someone who organizes and underwrites horse racing bets

- into a bookie for…—owing money to the above person

- hard boy—a muscular gentleman employed by a gangster (or bookie) to encourage payments of outstanding debts

- cop (verb)—receive money from gambling or from an enterprise that is not necessarily legal

- on the nut—out of money (also: broke; busted; stony; flat; on your uppers; out of readies; shaking two nickels together trying to get them to mate)

- having the bees—having lots of money (also: rolling in it; plenty of dosh)

- wrapped up in velvet—a man having married a rich woman

- haul—a large amount of cash, usually received from gambling or some questionable dealing

- juice—interest paid to a loan shark

- spondulix—money (also: mazuma; cabbage; cush; dough; lettuce; lolly; sugar; bread; scratch…)

- folding money—bank notes

- half—fifty cents

- berry—a one-dollar bill

- fin—a five-dollar bill (also: Lincoln)

- century—a hundred-dollar bill (also: c-note; yard; Benjamin)

- large—one thousand dollars, as in “I copped two large.” (also: grand)

- a portrait of Madison—a US five-thousand-dollar bill (featuring President James Madison)

- doing a nickel in the big house—serving a five-year prison sentence

(For these and even more arcane terms, read Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane, Dashiell Hammett or James M. Cain.)

Currency nicknamed

To round out this tale, let’s have a look at a menu of nicknames for specific denominations from all over the English-speaking world.

- dime: from the French word disme, meaning tithe (10% of one’s income given to a church)

- nickel: US and Canadian 5 ¢ coins which changed from silver to nickel to maintain their size and value

- penny: derived from the medieval English word penig, meaning a coin (German: pfennig, Swedish: penning, Estonia: penn)

- smacker, simoleon: a US dollar (origins unknown)

- angel: an English 15th to 17th century gold coin featuring the Archangel Michael (80 pence)

- bawbee: a Scottish 6-pence coin named for the Scottish mint master, the Laird of Sillebawby

- bluey, pineapple, lobster, watermelon: Australian terms for their bank notes, referring to their colours

- fiddy: a fifty-dollar bill in New Zealand

- quid: a British pound (possibly derived from “quid pro quo,” a favour granted in return for something)

- tuppence: an English coin worth two pence

- bob: a British shilling, possibly related to the 18th century politician, Sir Robert Walpole

- groat, noble, florin, guinea, farthing, sovereign, unite: a sampling of the wildly assorted denominations of historic British coins

So, what will our money be nicknamed in the future? Will we pull out a ten-dollar bill and call it a “Viola”? Doubloon instead of toonie? Who knows how these things begin? Create your own nicknames, and see how it goes.

The Museum Blog

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.