It’s big; it’s heavy; it’s called a rai. The large stone disk at the Bank of Canada Museum’s entrance is a multi-functional currency with a fascinating history.

What are rai?

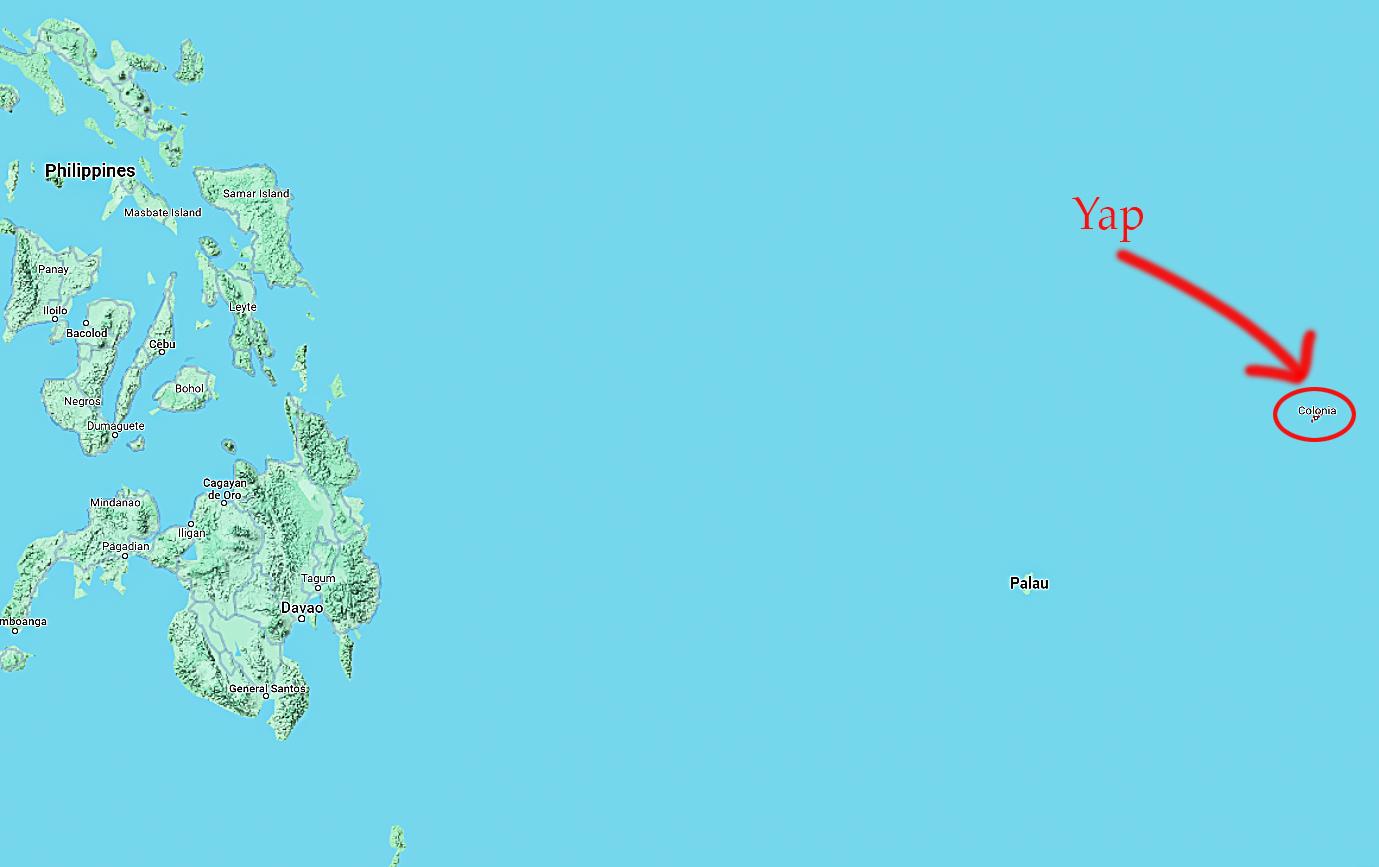

Rai are stone currency from the island of Yap in Micronesia. Also referred to as fei, they are all roughly the same design and come in a wide variety of sizes. Often the biggest rai were used for high-value or culturally significant purchases and ceremonies. The smaller ones, among other types of local currencies (pearl shells and necklaces, and woven mats), were traded directly for goods and services.

The Museum rai stands above the lobby at street level. The biggest one outside of Yap, it is 2 metres wide, 2.25 metres tall and weighs 1,800 kilograms. The material is aragonite, a component of limestone.

Source: rai, Yap State, Micronesia, 1870–1900 | 1975.79.1

The making of rai

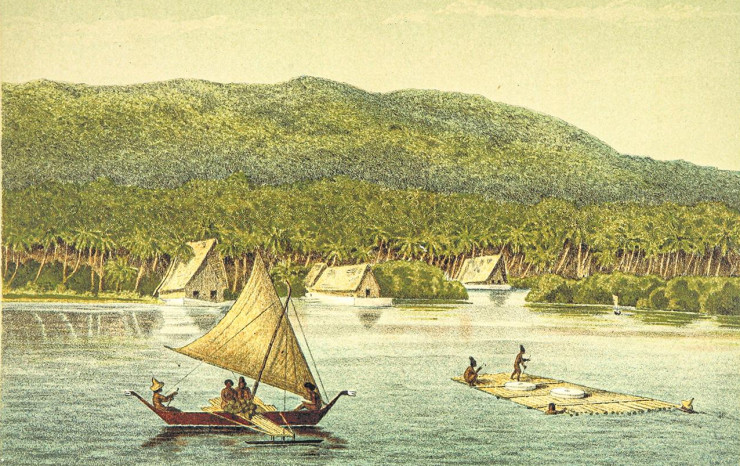

Before the Yapese people had any contact with Europeans, only a tribal chief could order new rai—although there is evidence that rai first arrived on Yap as gifts from the island of Palau. The Yapese chief would send sailors and carvers more than 400 kilometres to the archipelago of Palau—where all the stones were quarried and carved. This was no easy task because it meant days of sailing outrigger canoes across open seas, followed by months of back-breaking labour.

Once at Palau, the Yapese negotiated with the local chiefs for permission to access the quarries. They brought gifts and food or traded their own labour. Then began the slow and incredibly laborious task of carving discs out of solid limestone using tools made from shells and stone and, later, iron.

There could have been as many as 100 people working the quarries at the same time. Once the rai stones were returned to Yap, the biggest ones—and roughly a third of the smaller—would go to the chief. The rest, plus quantities of food, went to the sailors and carvers. The newly minted rai would then be displayed before their owners’ homes or in large areas in village centres that were essentially rai banks.

Spending the big money

Rai were not only physical wealth but also symbols of wealth—like diamonds or gold. As well, they had many practical roles, such as paying taxes, marriage dowries, land purchases or war settlements or buying political loyalty. Rai were also given as gifts from one village to another during festivals.

These transactions were all recorded in Yapese oral history—like today’s bank account statement or the publicly available ledger of a cryptocurrency. However, the Yap oral ledger also records cultural value—the significant history of a rai. Since all the information pertaining to a given rai was kept in the collective memory of the people, the stone itself never needed to move after a transaction. It just got reassigned by public assent. Only the smaller stones were moved.

There is a story—or possibly a legend—about a large stone that fell off a raft during a storm. After it sank, there was no need for the stone itself to be on hand; everybody knew it existed and to whom it belonged. It was still a functioning rai even at the bottom of the sea—like gold tucked away in an underground vault.

A rai’s visible value

Every dollar you spend represents a dollar’s worth of your time and effort at work. It is similar for a rai—but the rai also stores the value of the effort that was needed to make it and move it to Yap. That’s how a rai obtains its base value. Bigger generally means higher value because more labour is necessary, and transporting it is a greater risk. And artisanship matters, too. Stones with stepped faces or smooth surfaces were also worth more—again, because greater effort was invested. The quality (colour, smoothness, beauty) of stone also contributes to its value. But these are all visible, accountable aspects. A rai’s greater value is quite invisible.

A rai’s hidden value

An item is said to have cultural value when it can be directly associated with the history, people, beliefs or rituals important to a society. It’s the same with a rai—its value can be greater depending on who authorized it, who carved it and who subsequently owned it. Did anybody get injured or die when carving or transporting it? What significant cultural activities was it used in? Depending on its specific history, a rai can get more valuable with time.

But bigger is not always better

Although he wasn’t the first European to attempt to profit from Yap’s stony economy, adventurer David O’Keefe was the most successful. Shipwrecked on Yap in the 19th century, he learned about the stone money and came up with a way to profit from it. O’Keefe helped the Yapese quarry and transport stones from Palau with a steamboat, modern tools and possibly a little dynamite. They created bigger rai of higher value—a Westerner’s idea of value. In doing so, O’Keefe provided the Yapese with a service that allowed them to, quite literally, make more money. They paid O’Keefe with coconut meat and sea cucumbers, commodities common on Yap that O’Keefe resold at a huge profit in China.

Interestingly, despite the superior size and finer quality of the O’Keefe rai, they were actually worth less on Yap than many smaller and cruder stones—effectively creating inflation. O’Keefe stones weren’t authorized by any chief, were far less labour-intensive to make and gained no history before being traded. In short, they lacked cultural value. The sheer volume of stones brought by O’Keefe to Yap also depreciated their value. In essence, all that the stones really did was look impressive and cause inflation.

The two-level design, smooth surface and nearly round shape of this rai would make it more valuable. It was likely a later stone, possibly carved with metal tools.

Source: photo: Einsamer Schütze, Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, 2015

How many people would it take to move this rai? During installation at the Museum, placing it required a specialized lift truck. Mechanization made moving big rai possible.

Source: Bank of Canada Museum

The rai at the Museum

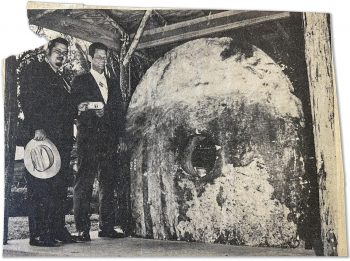

There are roughly 7,000 rai in the world. An estimated 13,000 originally existed. Rai have not been made since the early 20th century, and since the mid-1960s, none have been allowed to leave Yap. The rai in our collection was one of the last to do so. It’s thought to have been quarried around 1875 at Babledaob, an island of the Palau archipelago. Although we can’t be certain it’s an O’Keefe stone, its sheer size and level of workmanship seem to indicate it is. Its first owner of record was Puguw of Talingith, followed in the 1920s by Fathgol of Fugol u Tonil. Its final Yapese owner was Andrew Roboman, president of the Yap Island Council in the mid-1960s.

How the rai came to the Bank of Canada dates back to the mid-1970s, when a museum at the Bank was in the early planning stages. The National Currency Collection curator at that time, Sheldon Carroll, suggested purchasing a rai for the collection—he knew about one available in Florida. The Bank’s Governing Council approved, and Carroll negotiated its purchase in 1975. Today, the big stone disc acts as a sort of gatekeeper for the Museum. And its significant value as an artifact lies not only in its wow factor, but also in the ways it can be used to interpret the psychology that makes money work, its primary functions and its true value.

Rai still carry significant symbolic value for the people of Yap. The great stones still serve as reminders of a unique economic system that had real human value at its core; value that was communally determined and rooted in history and social trust. Currently, rai quarry sites on Palau and rai location sites on Yap are on the list of proposed UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

New research is always changing the way we think of and understand the National Currency Collection. If you spot any errors, or have any additional information about rai, please contact the Museum.

In 1965, Andrew Roboman sold this rai to Grover Criswell. For several years, Criswell displayed it at the Ripley’s Believe It or Not Museum in St. Augustine, Florida. Grover Criswell (left) is shown here with Ripley’s museum manager Robert Barclay (right).

Source: clipping, St. Augustine Record, Florida, United States, around 1966

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.