The Great Depression was a turning point in economic history—when the nature of money and how it is regulated changed forever.

The 1920s: Economies fueled by optimism

After the Allied victory in the First World War, a giddy economic confidence was growing everywhere in Canada and the United States. Modern technologies such as kitchen appliances, radios and cars were flooding the market—and all within reach of an eager population through the magic of credit.

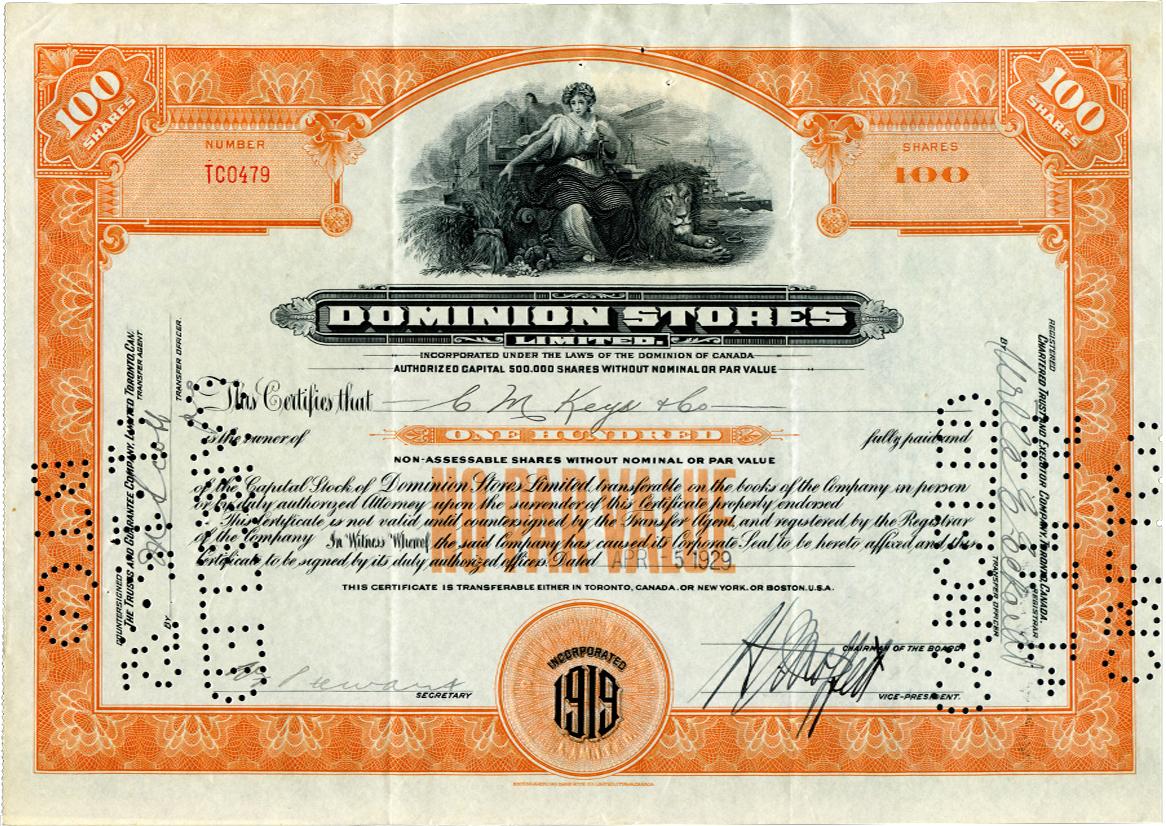

Credit also made it possible for the average person to buy into the red-hot stock market “on margin”—basically buying a stock with a loan. This meant a consumer could buy stocks at 40%, 30% or even 10% of their value, paying off the loan when the stocks sold for the enormous profits promised by brokers. By 1929, 40% of US consumer debt was being used to purchase stocks. Thousands of Canadians also spent all they could to get on board the stock market gravy train. There was widespread faith in a golden future of prosperity, and the markets soared.

1929: The bubble

An economic bubble is a buying cycle with a steep and constant price rise followed by an often-sudden vertical drop—like the expanding and bursting of a bubble. People buy into investment bubbles are speculating: buying items such as stocks believing that prices will continue to rise and provide them with an attractive profit upon selling. And so long as the supply of items stays fixed, the more buyers there are, the higher the value rises—and the longer people hold off selling. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy with a devastating ending. By the late summer of 1929, the US and Canadian stock markets had long since become textbook economic bubbles. Many chose to believe that this rocketing stock market was a clear reflection of a healthy, booming economy. It wasn’t.

Every age has its peculiar folly: Some scheme, project, or fantasy into which it plunges, spurred on by the love of gain, the necessity of excitement, or the force of imitation.

Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

The reality behind the bubble

The greater world of the 1920s was actually in pretty rough shape. Recovering from the First World War, Europe was flat on its back, and many nations had raised tariffs to protect their domestic production. World-wide, prices for most commodities were down, and global trade was in a slump.

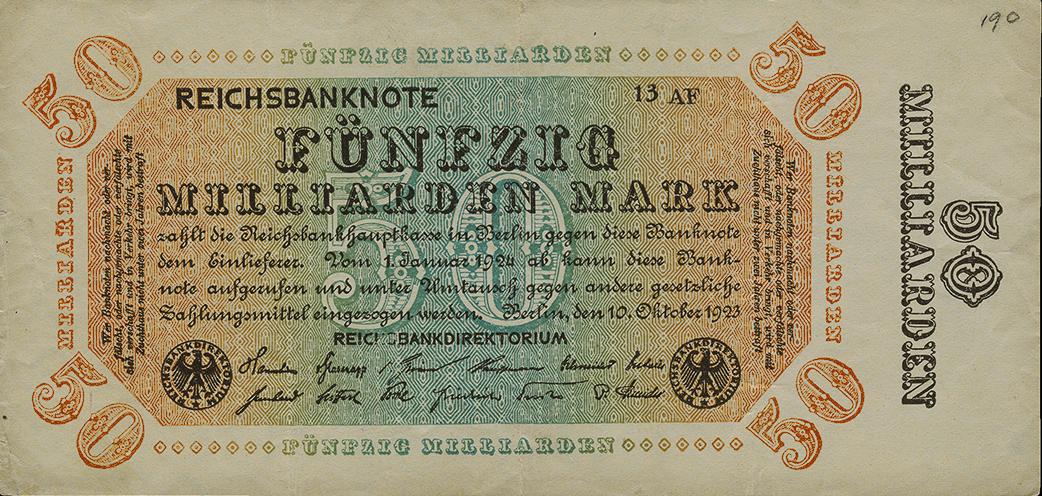

After the First World War, Allied nations forced Germany to pay for wartime expenses in gold. To do so, Germany printed tonnes of bank notes like this one. By the 1920s, Germany had out-of-control hyperinflation and notes like this were worthless.

Source: 50 billion marks, Germany, 1923 | NCC 1966.87.120

At home, Canada’s lumber, coal and wheat producers were having a hard time finding markets. To make matters worse, during the summer of 1929, the eight-year-long drought that would soon devastate the Prairies had begun. In the cities, wages had stagnated, and household debt was spiraling ever higher. All those cars, radios and washing machines had no offshore markets, and much of what North America could buy, it bought on credit. Something had to give.

The Great Crash

And something did give. In the autumn of 1929, stocks from big, reliable companies began to falter. The signs were telling stockholders it was time to sell. Brokers began to sell, and stock prices across all sectors started to drop significantly. Panicked selloffs followed pushing prices further down, encouraging even more selling. The bubble was bursting. By October 29th, at the end of several days of intense buying and selling, US$25 billion (US$450 billion today!) in personal wealth had simply evaporated from the New York Stock Exchange. The same thing happened in the Canadian exchanges. And all those hapless folks who bought stocks on margin? They had nothing to show for their investments but debt.

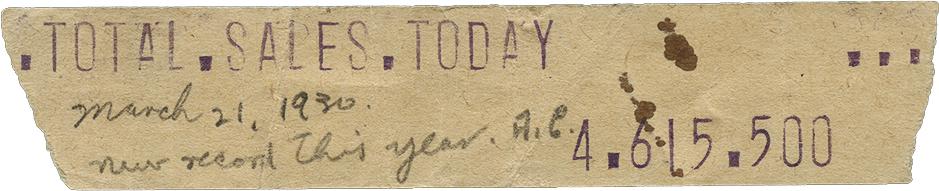

Wired up to telegraph services, a ticker tape machine would constantly type out the latest stock prices. During the 1929 stock market crash, trading was so frenzied that the machines couldn’t keep up, and many trades were made based on old information.

Source: ticker tape, Canada, 1930 | NCC 2019.22.4

The great fallout

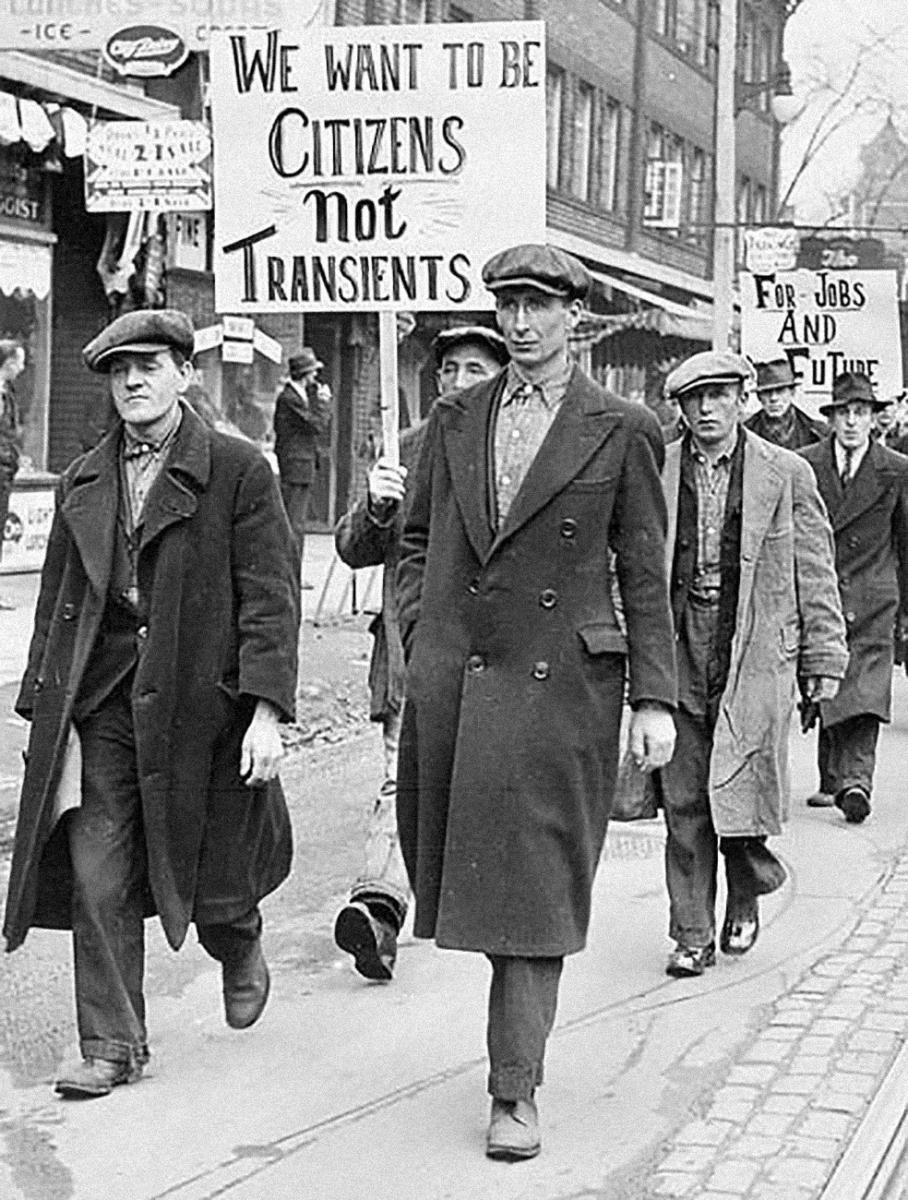

If you imagine the economy as a forest, the stock market is only one tree of many. But when that tree fell in 1929, it pulled down a whole lot of other trees with it. The commercial banks that Americans used every day were heavily invested in the stock market, something that is now illegal. Also, US banks were a fragile collection of small and disconnected independents. As they began to fail, people panicked and attempted to pull their savings from even healthy banks, causing more failures. Over 9,000 US banks would fail. Although not a single Canadian bank failed, the US was, and is, our biggest trading partner, so the effects of US failures reached deep into our economy. Credit disappeared overnight, forcing businesses to close. Unemployment soared on both sides of the border and civil unrest was on the rise.

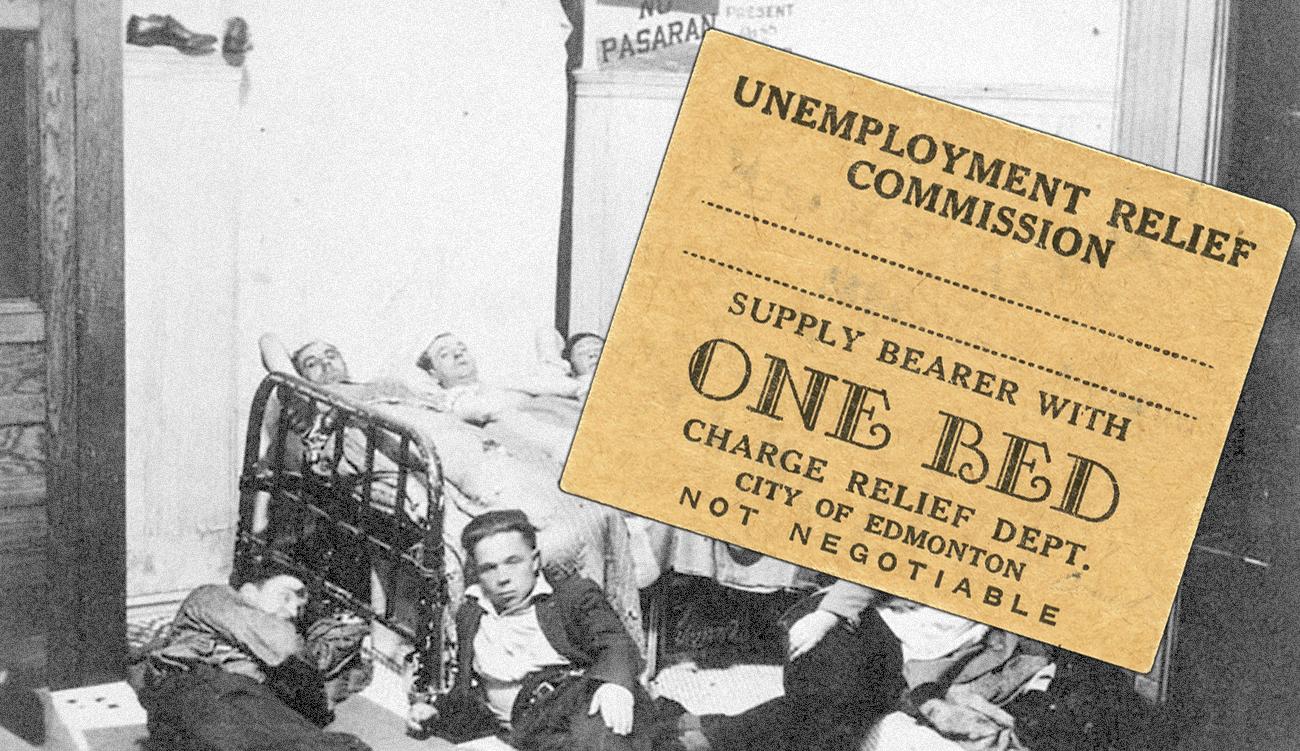

As a recession ramped up, prices for everything, including food and fuel, fell further, driving Canada’s agricultural and resource sectors into the ground. Saskatchewan, experiencing the lowest grain prices in history, lost 90% of its income in two years. By 1933, Canada’s gross national product had fallen by more than 40%, and 20% of the labour force was out of work. And there was hardly any support for unemployed workers. Homelessness and poverty became the norm for many thousands of Canadians.

The federal government pushed responsibility for the welfare of its population onto municipal and provincial governments—many of which went bankrupt.

Source: 1 night accommodation, welfare ticket, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada | NCC 1975.47.6

Radio-Canada, Library and Archives Canada, around 1936 | C-013236

Obstacles to relief

One of the biggest restraints to solving the crisis on either side of the border was the gold standard. At that time, the amount of money in a nation’s economy was tied directly to how much gold it had in its vaults, and anybody holding cash could exchange it for actual gold. So, for a government to find the money to create jobs, it needed more gold. And in the United States, some of those gold reserves were heading overseas because foreign holders of American currency were panicking and converting their cash to gold. So, the US Federal Reserve Bank pushed interest rates higher and higher, boosting the value of the dollar to discourage investors from converting it to gold. This would help keep the gold at home. But raising interest rates also choked off credit that could have revitalized the economy. This process was actively making the Great Depression worse and did so throughout the 1930s.

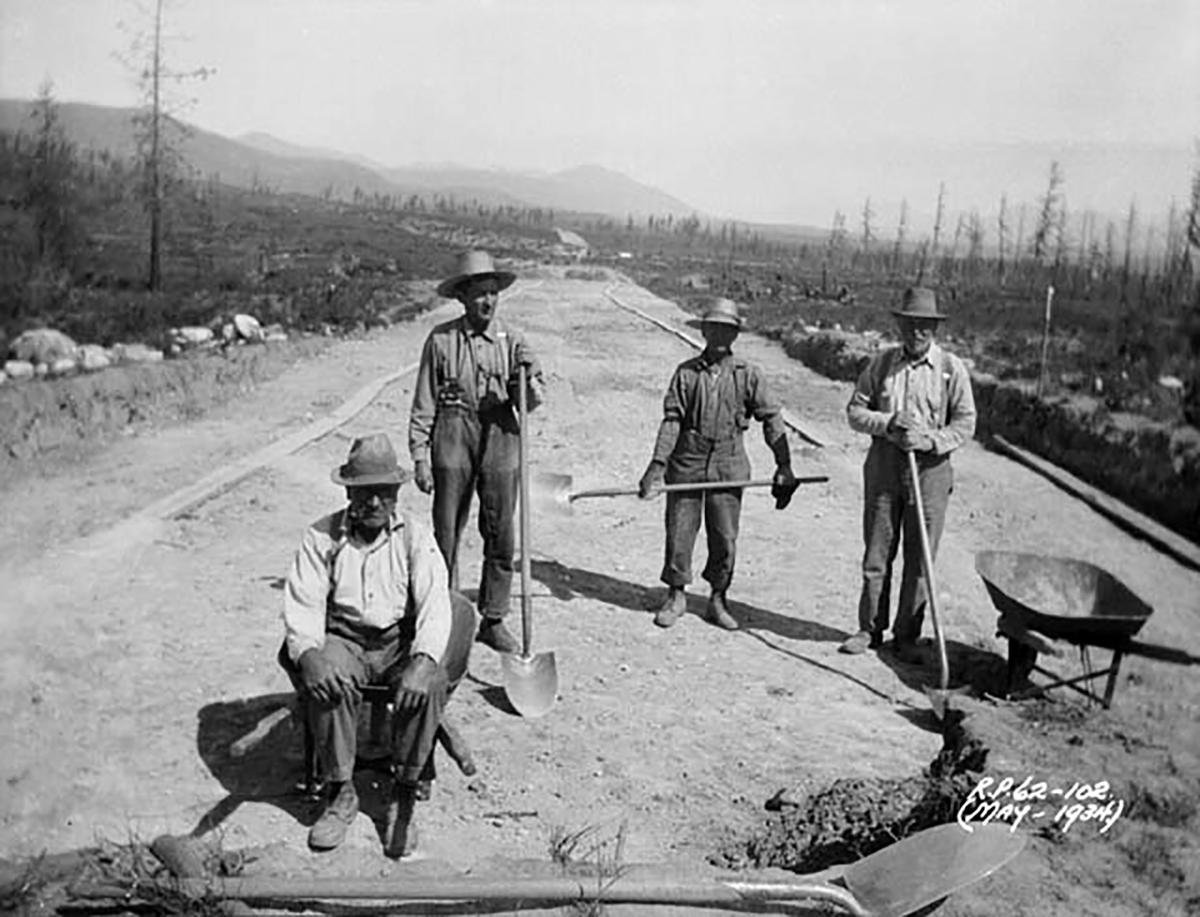

Canadian Prime Minister R.B. Bennett introduced some make-work projects and work camps. Remotely located, these were more like prison camps. Workers such as this road crew near Kimberley, BC earned 20¢ an hour. ($4.00 today)

Source: Department of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada, 1930s | PA-036089

Getting around the obstacles

The modern practice of governments spending money in times of recession was a shocking idea to most politicians of the 1930s. This practice reflects the theories of economist John Maynard Keynes: If a slump occurs, spending falls and a recession follows. Therefore, to get out of a slump, spend. This is just what American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt did in his economic solution package of 1933. Called the “New Deal,” it created jobs and got money moving again. He also suspended the gold standard. The Federal Reserve Bank’s consistent rate hikes still hindered the money flow, and the New Deal wasn’t able to turn things around completely, but light began to shine at the end of the tunnel.

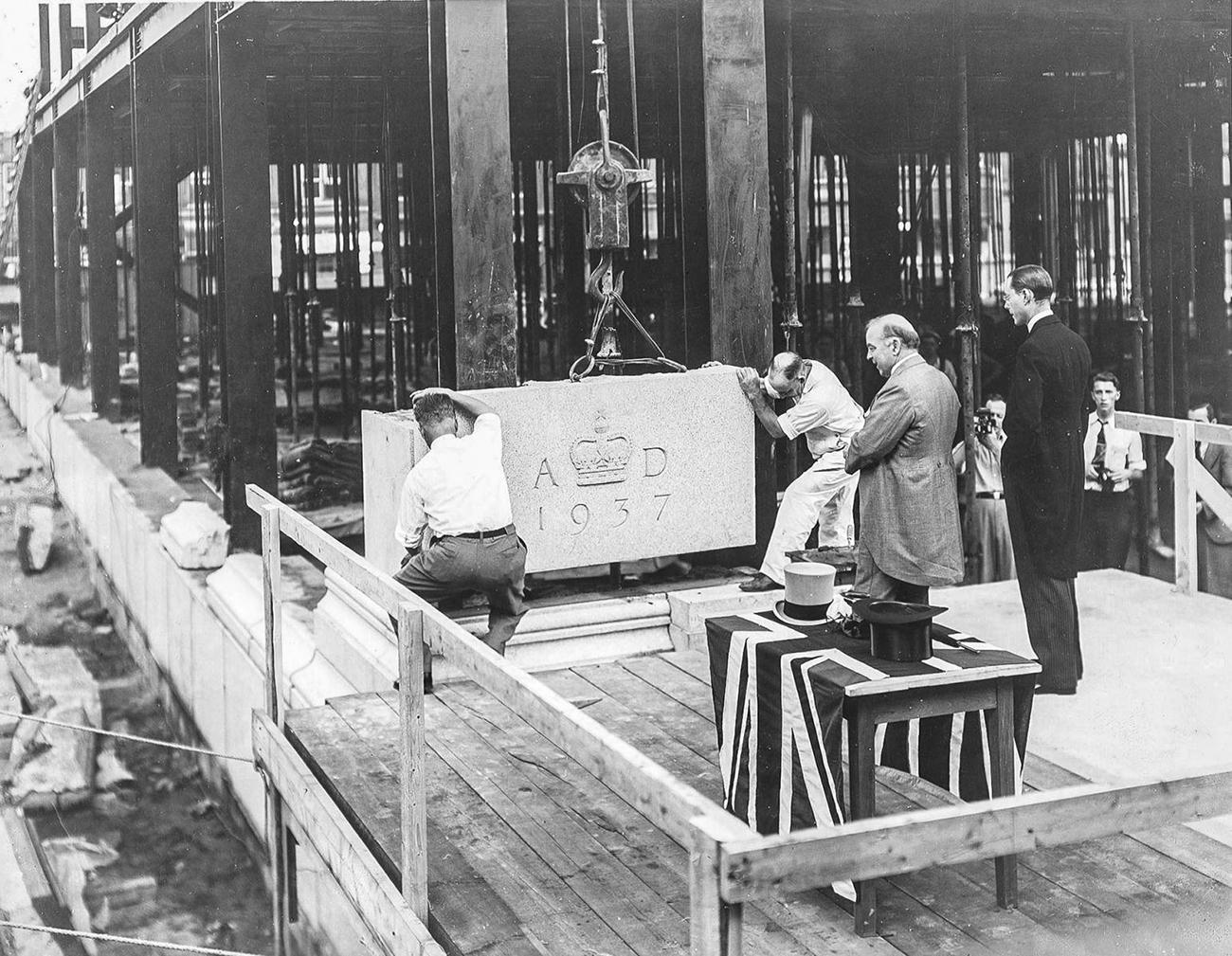

In Canada, Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett proposed a similar scheme in time for the 1935 election. It included welfare, minimum wage and large public spending. However, provincial governments saw the proposal as a threat to their authority, and most of the plan was defeated in the courts. But one of the surviving recommendations was for a central bank to regulate the economy. And, in 1935, the Bank of Canada was born.

Over the following years, the Bank was to provide stability for our banking system. Canada had gone off the gold standard during the First World War and did so again in 1931. The Bank continued to distance itself from what was a restrictive and outdated system. This freed up credit but there was little the Bank could do to solve many of the underlying problems of the Great Depression. Overseas markets for our products remained flat, as did prices.

And drought continued to rage on and off throughout the Prairies until the summer of 1937—holding back a recovery in Canada. Hundreds of thousands of farms failed and were repossessed or abandoned. Significant portions of the West’s populations migrated out of the Prairies or to the cities.

Sadly, it took one of the greatest human catastrophes in history to finally motivate spending and end the Great Depression: the Second World War.

Lessons learned

Though it is still debated, for most historians, the Great Crash is no longer solely blamed for the Great Depression. It was certainly a catalyst, but governments’ inability to cope with its aftermath is now widely regarded as having caused the continued conditions of the Great Depression. What the stock market crash of 1929 did was starkly reveal the weaknesses of economic systems that had evolved from the unregulated capitalism of the late 19th century. Most of the men running the power structures of the early 20th century didn’t have the foresight, flexibility, or innovative thinking to avoid a world-wide depression. Nowadays, it’s a very different picture.

Though naturally it is debated, current thinking says that we cannot expect an economy to simply take care of itself, or for financiers and brokers to police themselves, either. Yes, an economy can function like a theoretical machine—but only when it’s regulated and operated carefully with an eye on the humanity involved.

…human decisions affecting the future, whether personal or political or economic, cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation…

John Maynard Keynes

What Mr. Keynes meant was that when we think about the economy, we must also consider all the needs, wants and temptations of people—all those human vulnerabilities that deeply affect an economy yet are so very difficult to account for. So, periodic economic upsets will continue to happen in new and unexpected ways, and authorities will need to be flexible and long-sighted when they step in to resolve them.

A depression could have occurred in the aftermath of the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis or even the COVID-19 pandemic. But it didn’t. Yes, the resolutions to those upsets involved painful financial sacrifices, greater burdens of debt and fears for the future. But as for that lost decade of hunger, deprivation and hopelessness, anger, and dreams of a new order, it’s comforting to know that it’s unlikely we’ll experience anything quite like that again.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.