How Newfoundland lost its money by joining Confederation

The last vestiges of Newfoundland’s currency disappeared with the signing of the Terms of Union. Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation marked the end of an era when colonies issued their own coins and paper money.

Newfoundland: island of cod

When John Cabot landed at Bonavista in 1497, he claimed the island for King Henry VII of England, who called it the “New Found Launde.” It is ironic that for centuries Newfoundland (and today, Labrador) was remembered less for the "land” than for the seas and their abundance of cod fish beyond her shores. In fact, some early 16th century Portuguese maps called it terra do Bacalhau or ilha do Bacalhau, “land” or “island of cod.” Given that cod would drive the colony’s economy for the next four hundred years, maybe the Portuguese name would have been more suitable.

Several Indigenous Peoples in North America—including Inuit, Innu, Wolastoqiyik, Mi'kmaq and Beothuk—have fished the Atlantic cod for thousands of years. What we call Newfoundland today was known as Ktaqmkuk when Europeans first landed on the island. It was inhabited by the Beothuk and Mi’kmaq at that time.

Newfoundland became the site of an international fishery. Portuguese, Spanish, Basque, French, English and Dutch fishermen were active on the Grand Banks. Boats from ports all over Europe would cross the Atlantic Ocean in the spring, crowd the waters off the coast to cast their nets, and set up temporary camps on the shores to dry their catch. They had little interest in the island or the people that called it their home. For them, it was all about the fish!

Permanent settlement, fish currency and coinage

For nearly 200 years after Cabot’s landing, Newfoundland remained largely uninhabited by Europeans. In 1610, a few English fishers wintered at Cupids, located in the Avalon peninsula. After a couple of years, the population at the site was 62 people, including a few families. A decade later, in 1623, England chartered the colony of Avalon, with Ferryland as its main settlement. It was founded mainly to support the fishery. The French gained residence in Placentia (a variation of Plaisance), located on the other side of the peninsula, in 1655. The coexistence between English and French settlers during those years was tense and even violent. One campaign, launched by French forces, began in 1696 with the raiding of the Ferryland settlement. The campaign destroyed 23 English settlements along the coast of the Avalon Peninsula in the span of three months.

Following this destruction, England passed new legislation in 1699 allowing permanent English settlement in Newfoundland to protect its fishing interests against any French aggression. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 permanently ceded Newfoundland to Great Britain, although the French maintained special fishing privileges with a base on the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon. Despite the British government effectively discouraging settlement, Newfoundland had a population of about 2,000 settlers by 1700. The arrival of European settlers introduced diseases such as tuberculosis, which took an enormous toll on the Beothuk. A lack of both resources and outside help to confront the disease led to a decline in their numbers throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, until the Beothuk eventually disappeared.

Coinage was scarce in Newfoundland, a phenomenon not uncommon in many English colonies around the world. For decades, commerce on the island operated on a credit system, with dried cod as the local trade commodity. In the spring, merchants on the island would outfit the fishermen with equipment, and the fishermen would settle their account in the fall with their seasonal catch. Merchants exported the salted and dried cod to Europe, South America and the Caribbean. Reliance on a credit system and the extensive use of bills of exchange to settle transactions between the island merchants and their suppliers in Europe further prove the lack of coinage. Coins were not available in any reliable quantity for commerce, let alone for capital to help grow the economy.

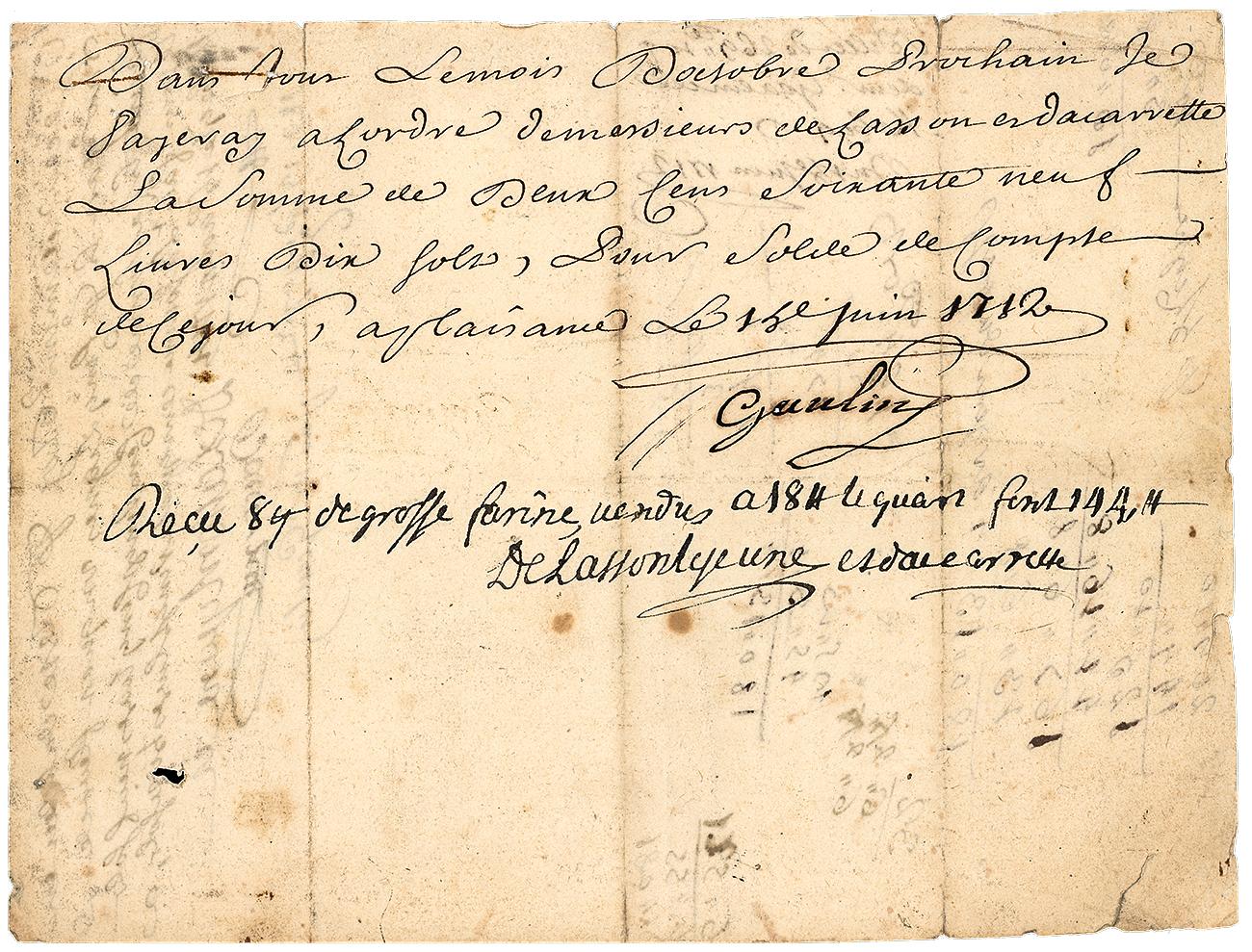

In this handwritten note, Robert Gaulin promised to pay Messrs. de Lasson and Dacarrette £269.10 in October 1713 to settle accounts. Notations on the note reveal that repayment of the debt was made in installments of heavy flour.

Source: Placentia, Newfoundland, Robert Gaulin, promissory note, 1712 | NCC 2002.10.1

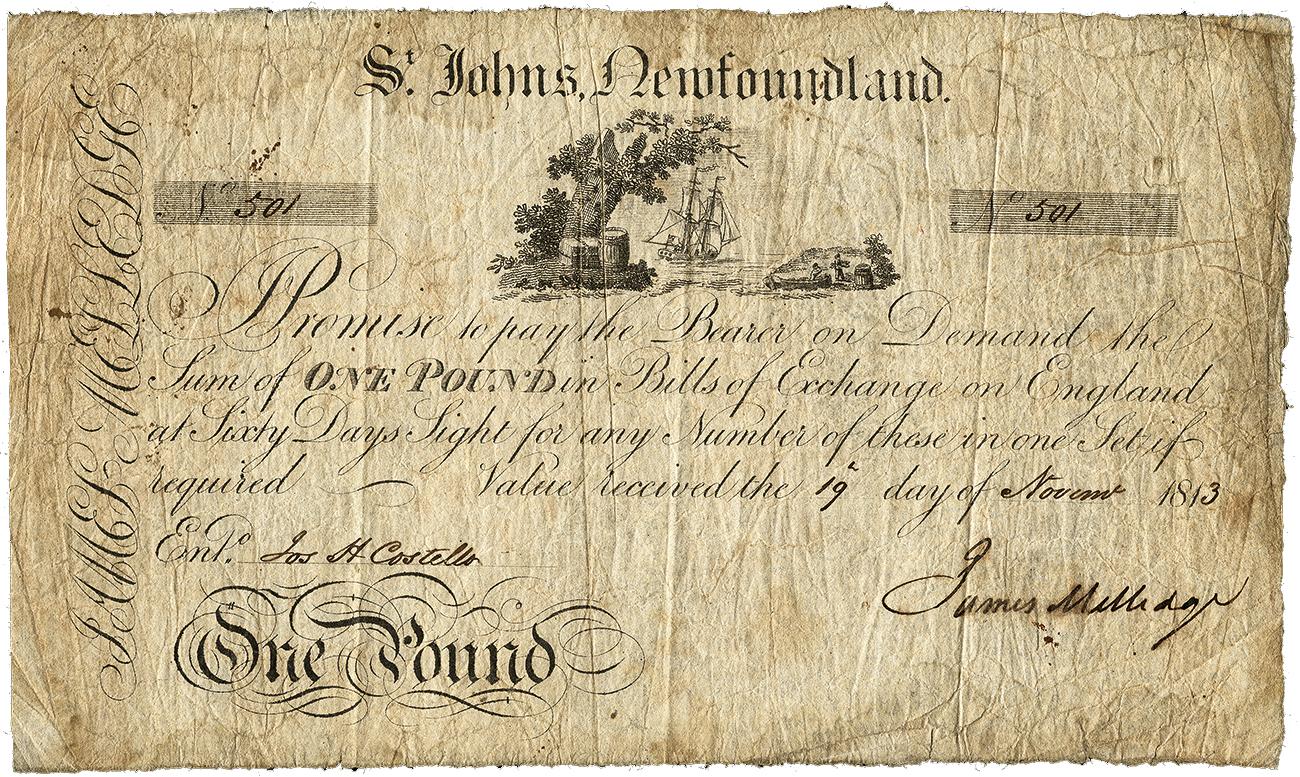

Promissory notes like this £1 note from James Melledge of St. John’s were like pre-printed IOUs used in local trade. The generic form of the notes payable to the bearer allowed for them to circulate and be accepted like a currency in the absence of official coins and notes.

Source: Saint John’s, Newfoundland, James Melledge, 1 pound, promissory note, 1813 | NCC 2005.21.3

Self-government and the fish economy

Throughout the 19th century, as Newfoundland was maturing from a migratory fishing stop-off to a self-governing British dominion, the booming cod fishery industry was attracting immigrants to the island for employment and income. Economically, the colony prospered thanks to the fisheries, which accounted for 60% of its economic activity and, in 1884, provided more than 90% of its exports. The Newfoundland government under the anti-Confederate sentiment of the Conservatives in power rejected invitations to join Canada in 1867. Yet by the close of the century, cod exports were in steep decline, affecting the colony’s potential for economic growth. In the late 1870s, recourse to other industries, such as lumber, pulp and paper, and mining seemed promising. But a lack of infrastructure, especially a means of transportation to access the interior of the island, hindered their progress. The ballooning cost of constructing a railway didn’t help. As well, low revenues and growing debt complicated matters for government projects, and the shortage of available currency aggravated the problem. All of this had consequences for Newfoundland’s delay in joining Confederation in 1949.

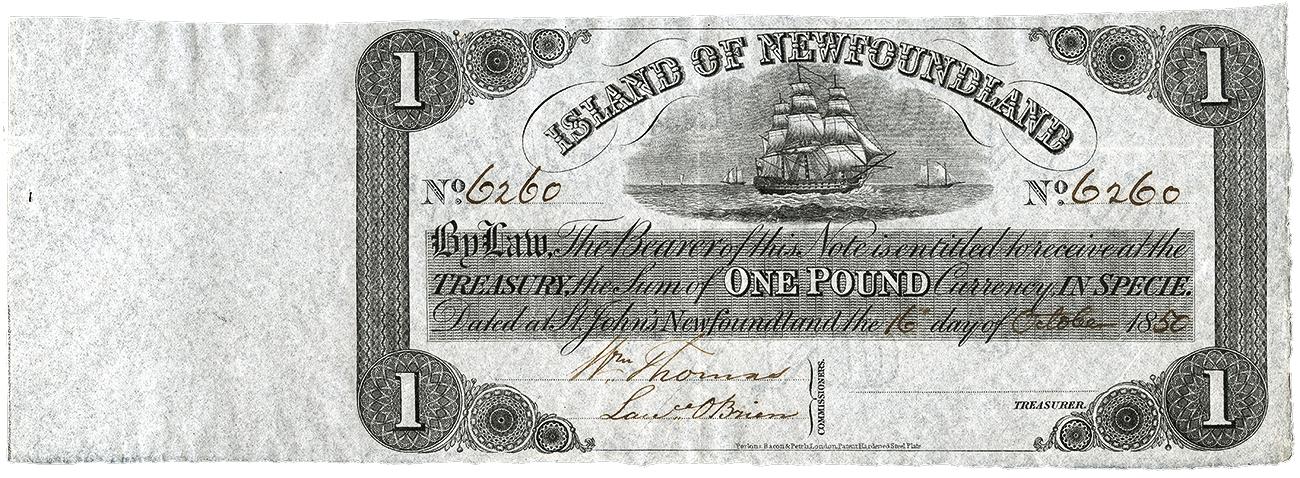

The first paper money for general circulation in Newfoundland were notes of £1 and £5 drawn on the provincial treasury. The Newfoundland government continued to issue notes well into the 20th century.

Source: Newfoundland, 1 pound, treasury note, 1850 | NCC 1964.3.1

Provincial coins and paper money

Before joining Confederation, each British North American colony had its own coinage. Even Prince Edward Island had its own cent in 1871! Yet Newfoundland’s coinage was exceptional. It was the only colony to issue a gold coin, and it minted coins over several years until 1947. The Newfoundland legislature passed An Act for the Regulation of the Currency (26th Victoria, Chapter 18, 1863), changing the currency to dollars and cents and outlining values and specifications of the coins. The range of coins for circulation included the bronze 1 cent; silver 5, 10, 20 and 50 cents; and gold $2 coins. As well as minting coins, the Newfoundland government also issued notes drawn on the provincial treasury for funding projects. Two homegrown chartered banks, the Commercial Bank of Newfoundland and the Union Bank of Newfoundland, issued bank notes.

To meet the Newfoundland government’s pressing need for coinage in 1864, the Royal Mint modified dies made for New Brunswick coins as a first trial for a new series. Delays in production, however, gave the engravers time to come up with new, original designs for Newfoundland coinage in 1865.

Source: Newfoundland, Victoria, 2 dollars, pattern coin, 1864; New Brunswick, Victoria, 10 cents, coin, 1864 | NCC 1973.117.12; 1975.90.7

Newfoundland is the only government in the world ever to issue a $2 gold coin. Originally, officials thought of having a $1 coin like the one used in the USA. But that coin’s small size (only 13mm) put it at risk of getting lost. A larger coin was a better option. $2 gold coins were minted for only eight years, between 1865 and 1888.

Source: Newfoundland, Victoria, 2 dollars, coin, 1888 | NCC 1970.110.5

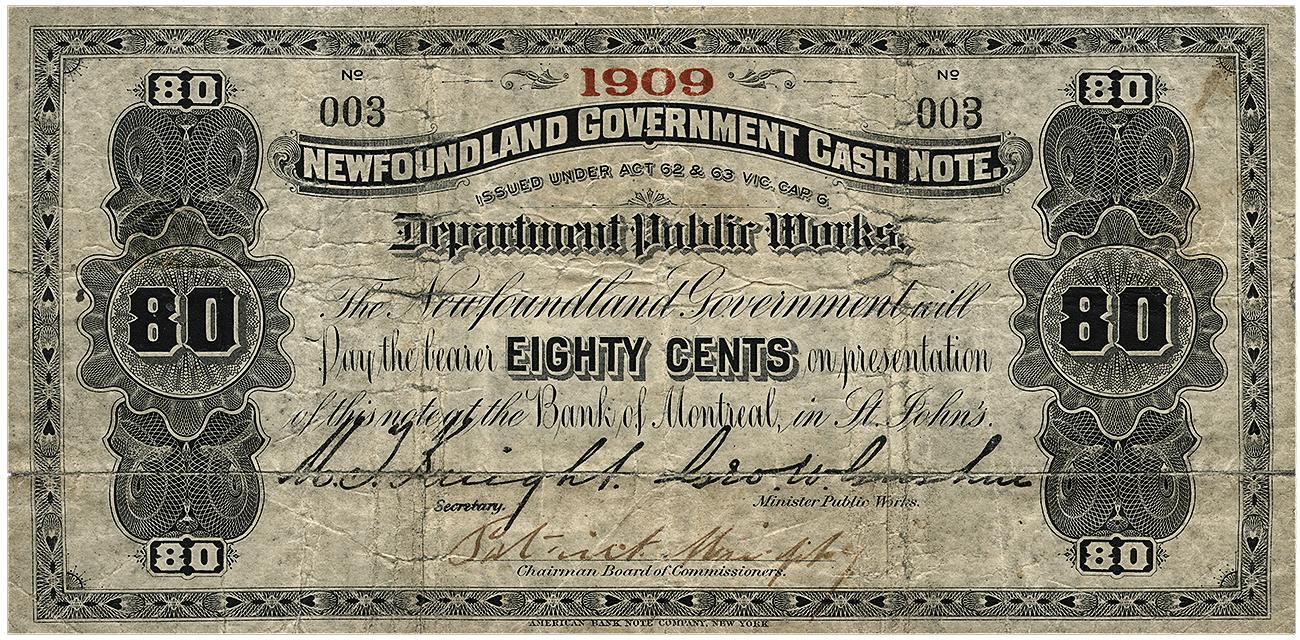

The Public Works department issued cash notes to pay for road construction and maintenance. The unusual denomination of 80 cents relates to the exchange rate between a British £1 gold sovereign and its Newfoundland currency equivalent of $4.80.

Source: Newfoundland, 80 cents, cash note, 1909 | NCC 1964.88.454

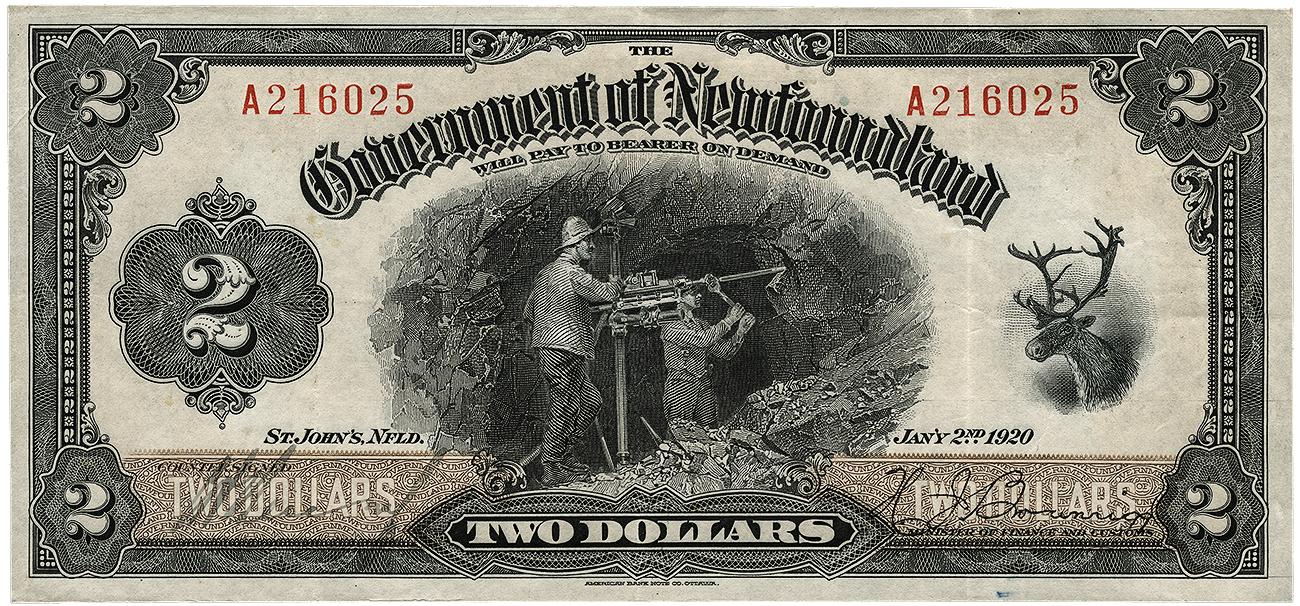

The last of Newfoundland’s paper money featured a mining scene: an industry in which the island had high hopes to put its economy back on the road to prosperity after the decline of the cod fishery.

Source: Newfoundland, 2 dollars, note, 1920 | NCC 1963.14.3

Financial panic and the fall of the Newfoundland banks

Newfoundland’s two banks, the Commercial and the Union, were the main providers of capital and currency for the colony. Yet by 1894, with a drying up of the cod fishery, difficulty in increasing mining output and rising costs to build the railway, the banks’ finances were stretched thin. They were overdrawn on their loans and riding the edge of insolvency. Acting on these rumours, people quickly sought to withdraw their money from the banks, only to learn that there were no funds to do so. Unable to meet their financial obligations, both banks permanently closed on December 10, 1894. The effects were immediate with businesses failing, workers losing their jobs and the price of food and other essentials rising. The entire colony was on the verge of bankruptcy. Payment of specie was suspended until Newfoundland passed legislation to wind up the affairs of the failed banks and for others, namely, the Bank of Montreal, the Bank of Nova Scotia and the Merchant’s Bank of Halifax (later, the Royal Bank of Canada), to come to the rescue. Notes of the Commercial and Union were redeemed at huge discounts. The inhabitants of Newfoundland who had faith in the banks to protect their savings lost almost everything.

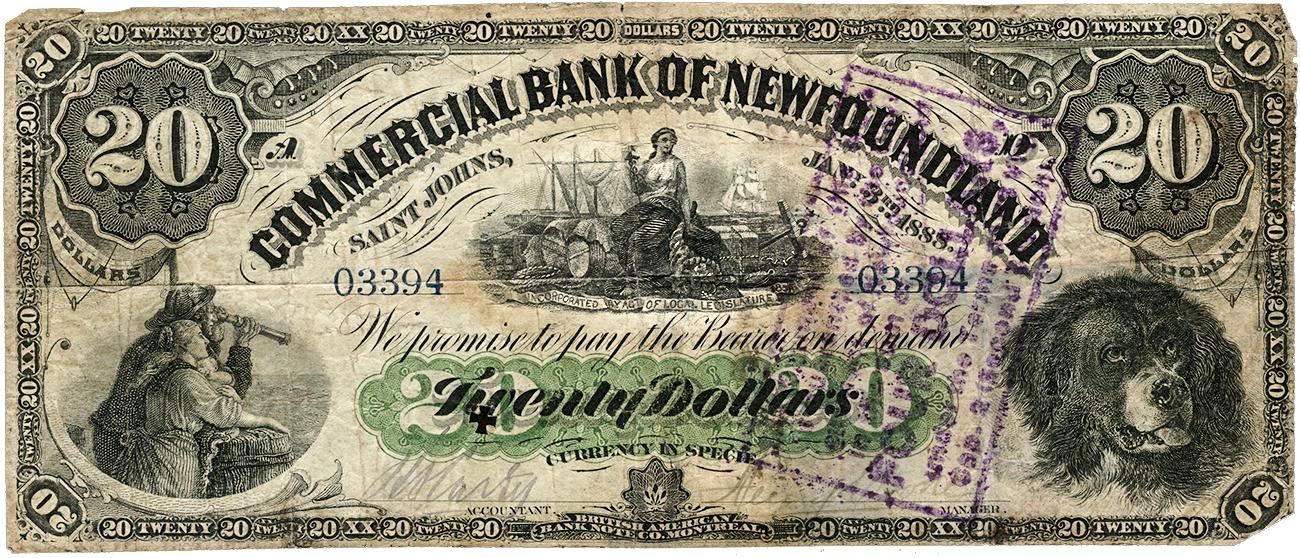

The purple stamp on this note adjusted its value to $4 for redemption by the Newfoundland government after the Commercial Bank’s failure.

Source: Commercial Bank of Newfoundland, 20 dollars, note, 1888 | NCC 1989.29.8

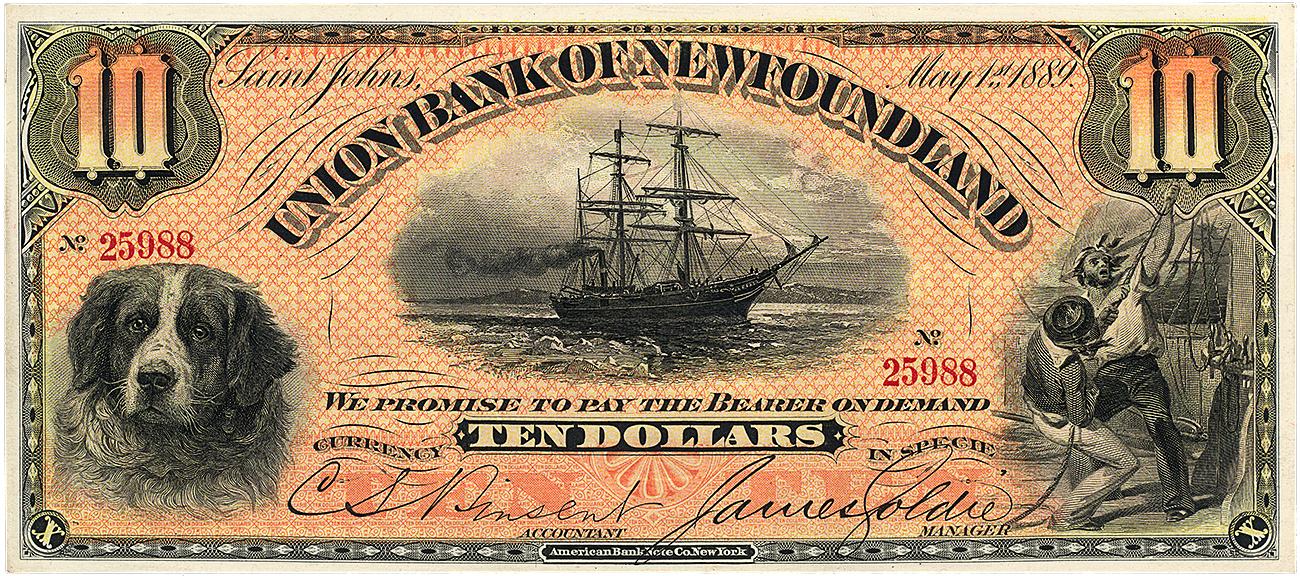

The vignette of the loyal, stoic and alert Newfoundland dog on this Union Bank note could not protect the bank from imminent failure. It was a victim of the same financial troubles that afflicted the Commercial Bank.

Source: Union Bank of Newfoundland, 10 dollars, note, 1889 | NCC 1964.37.6

The 20th century and a new attitude toward Confederation

Newfoundland never fully recovered from the 1894 financial crisis. And over the decades that followed, the option of joining Confederation seemed more and more attractive. The problem was that the rest of the Dominion of Canada was less enthusiastic about accepting it and its economic troubles. Throughout the First World War and the Great Depression, Newfoundland’s financial situation was desperate—so much so that, in 1934, the British parliament suspended the Newfoundland government and appointed a commission of government in hopes of steering the colony toward recovery. The Second World War turned around the colony’s fortunes, with increased immigration and influxes of money for the war effort. Newfoundland was again on the road to economic and financial stability, right in time for talks on joining Confederation to resurface.

1949: Newfoundland finally joins Canada

In December 1945, the British parliament announced that Newfoundland would hold a National Convention to choose the colony’s political destiny: self-government or union with Canada. The factions were equally split, but the pro-Confederation delegates led by Joey Smallwood won the motion to go to Ottawa to discuss terms for joining with Canada. While several delegates of the National Convention rejected the draft terms, disagreeing over the style of government, active campaigning in favour of Confederation allowed for the option to remain on the referendum ballot. On June 3, 1948, Newfoundlanders went to the polls. In a low turnout, the votes were split, with no clear winner. The results of a second referendum held the following month gave Confederation the nod. The final Terms of Union were signed on December 11, 1948, and in February 1949, the Canadian Parliament ratified them. Newfoundland was in. Labrador was physically separated, but had always been a part of Newfoundland. To reflect this, the province changed its official name in 2001 to Newfoundland and Labrador, recognizing it as a single entity.

A special coin to mark the occasion

To celebrate the event of Newfoundland joining Confederation in 1949, the Royal Canadian Mint issued a special silver dollar. It was only the third commemorative coin that the Mint had ever produced, but it was for a memorable moment in Canada’s history! The reverse of the special coin featured the Matthew, John Cabot’s flagship, which brought him to Newfoundland in 1497.

Newfoundland currency: a collecting legacy

Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation marked the beginning of a new era in Canadian history. But for Newfoundlanders accustomed to using their own money, the event must have caused some concern. Even though Canadian coins and Bank of Canada notes had circulated at par in the province for years, Newfoundland currency was special in many ways. The designs were different, the values were different, and Newfoundland had a gold coin that was unique in the world. Most importantly, coin and note issues lasted for decades, unlike the one-offs from colonies such as the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. For currency collectors, Newfoundland coins and paper money still attract a very active niche of the market, with a deep and passionate support base. The money has long been out of circulation, but the nostalgia endures.

The Museum Blog

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.