We’ve wrapped up the Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisition program for 2023. Here are a few highlights of the latest additions to the National Currency Collection.

The National Currency Collection keeps growing

One of the ways that the Museum grows its collection is by purchasing objects from private individuals or at public auctions. With careful planning, curators ensure that the National Currency Collection remains up to date with objects that tell important stories about economic and numismatic history, both in Canada and around the world.

Bitcoin tokens

In an increasingly digital age, finding physical objects to illustrate what’s going on in the virtual world can be difficult. But sometimes things that you thought only existed digitally, like cryptocurrencies, also have a material existence. American Mike Caldwell founded the company Casascius and minted the first physical Bitcoin tokens in 2011. Each token was loaded with various denominations of the famed cryptocurrency. Buyers removed holographic security stickers from the back of the tokens to reveal private keys (passwords) that let them access the funds. Casascius continued to release several tokens until 2013.

Other companies have since released their own physical versions to store bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Quebec-based Cryptolator was one of them. It created a physical token for Bitcoin that featured a cheeky design showing a group of people running away from a bank building, the chains that had bound them to the bank breaking behind them. Neither token acquired for the National Currency Collection is still loaded with bitcoin, but they nevertheless provide physical evidence of the cryptocurrency’s existence.

Royal Africa Company mark

In 1672, King Charles II granted a royal charter to the Royal African Company of England. A trade company much like the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Royal African Company operated along the coast of West Africa, exporting gold to England and transporting over 200,000 slaves across the Atlantic Ocean. The company’s charter specified that the Crown retained two-thirds of the exported gold. The company kept the rest as profit. The gold that flowed into the royal coffers was used to mint coins that bear a mark below the portrait of Charles II: a small elephant with a riding seat known as a howdah on its back. Few artifacts create such an explicit connection between capitalism and colonialism, making this an invaluable addition to the Museum’s collection.

Donations and gifts

The Museum also relies on the generosity of the public to keep growing the National Currency Collection. And Canadians stepped up again in 2023. They provided interesting and unusual items.

Janson Quessy’s collection of Canadian dollars

In the spring, the Museum received a donation offer of a collection of Canadian dollar coins from Janson Quessy, a long-time collector from Montreal with a passion for silver dollars. After reviewing Mr. Quessy’s collection, the curators observed several things that piqued their interest. First, the Quessy collection had many varieties of dollar coins that were not yet represented in the National Currency Collection—some of which have been found only in recent years. Second, the condition of many of the pieces in the Quessy collection are superior to those in the Museum’s collection. Third, and most notable, the Museum’s collection of commemorative silver dollars, which stopped in the mid-1990s, is now complete up to 2022; all the major types being included. Mr. Quessy’s donation improves the quality and depth of the National Currency Collection. A welcome addition!

Highlights of the Barrett-Minardo collection

In July, the Museum acquired some important Canadian bank note models and proofs from the collection of William L.S. Barrett and Katherina Minardo of Montreal. Among the over 300 items are holdings of the former American Bank Note Company of New York and the British security printing firm, Perkins, Bacon & Company. Mr. Barrett and Ms. Minardo acquired some items when the American Bank Note Company’s archives were sold at public auction in 1990. The Perkins, Bacon & Company inventory, which had been dispersed in the years after the company went bankrupt in 1935, was patiently assembled over the decades.

Proofs and dies of Perkins, Bacon & Company

Perkins, Bacon & Company opened in 1819 and provided security printing services to banking institutions around the world, including the Bank of British North America. The company was also famous for printing the penny black postage stamp, which was the earliest adhesive stamp for a public post office. The Bank of British North America was one of only two British-based banks to operate branches across Canada between 1836 and 1918 when it merged with the Bank of Montreal. The notes of the Bank of British North America are interesting because most of them indicate the city where the notes were redeemable, from St. John’s, NL, to Victoria, BC. But the ultimate prize in this collection is the proofs for the $500 and $1,000 bank notes, which are unique. Such high-value notes were not needed for daily commercial use, and likely none were ever printed or issued. The addition of some original printing dies used to print the Bank of British North America notes was a welcome gift to complement the collection of proofs.

Models from the American Bank Note Company

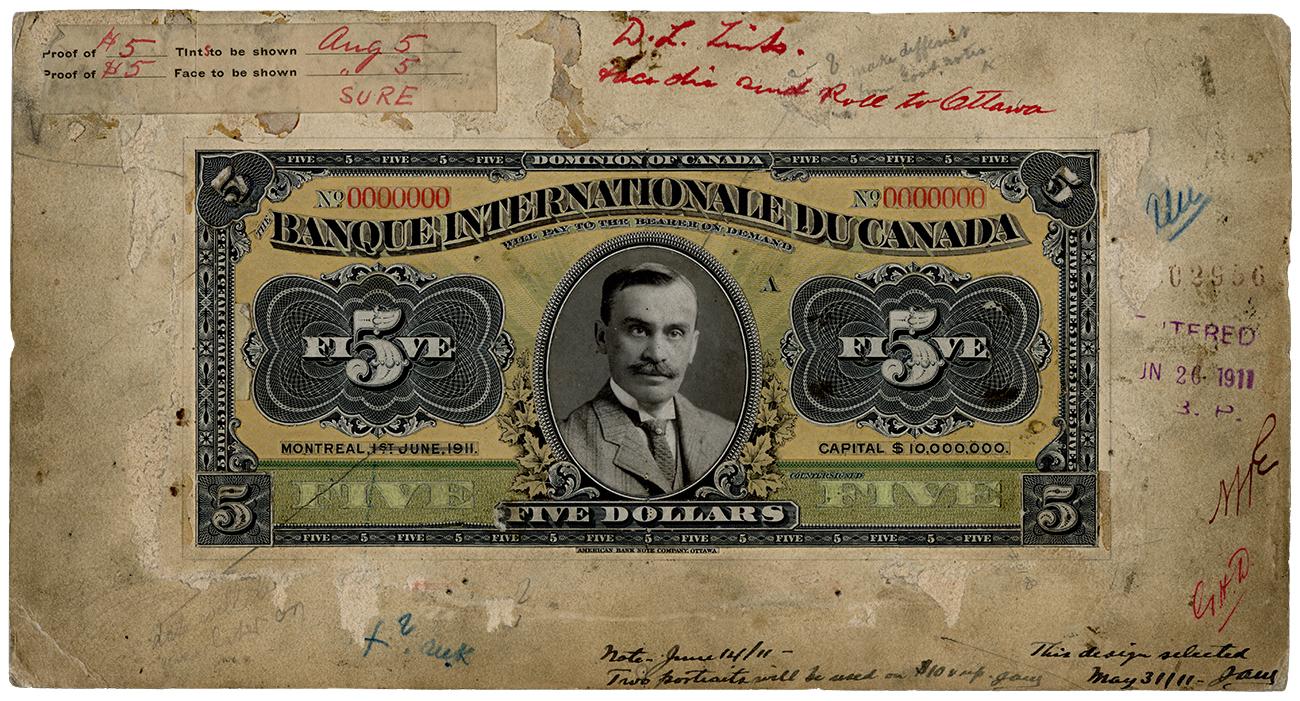

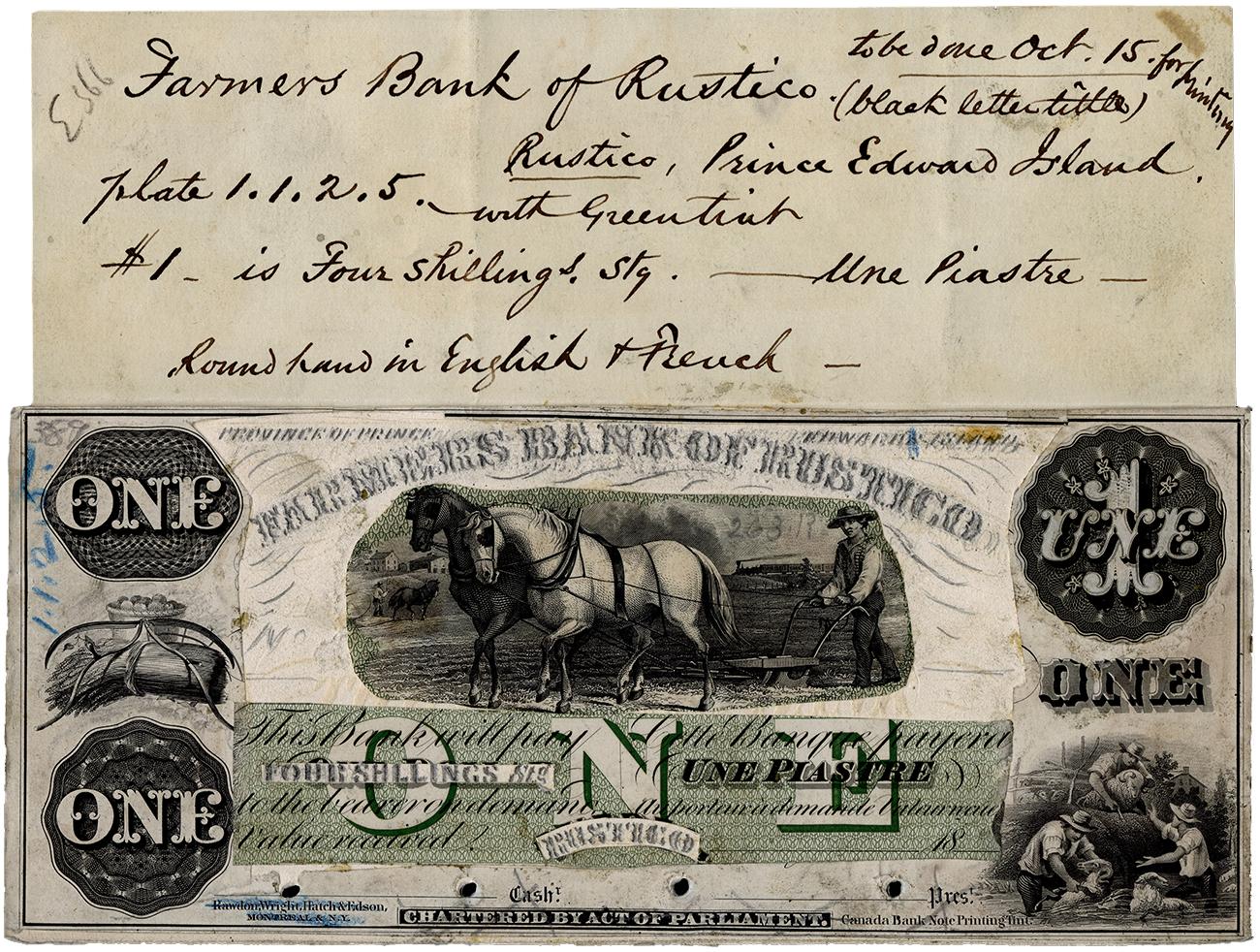

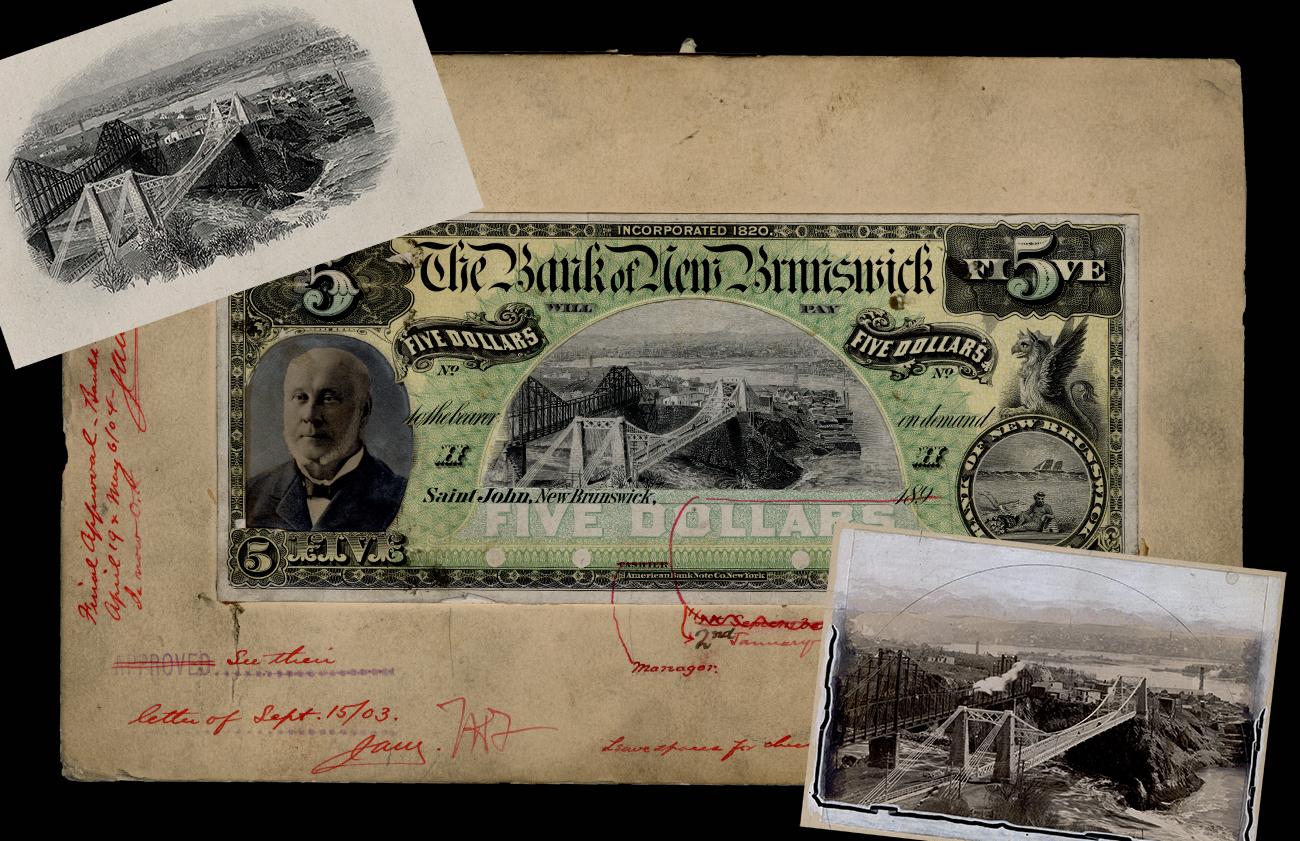

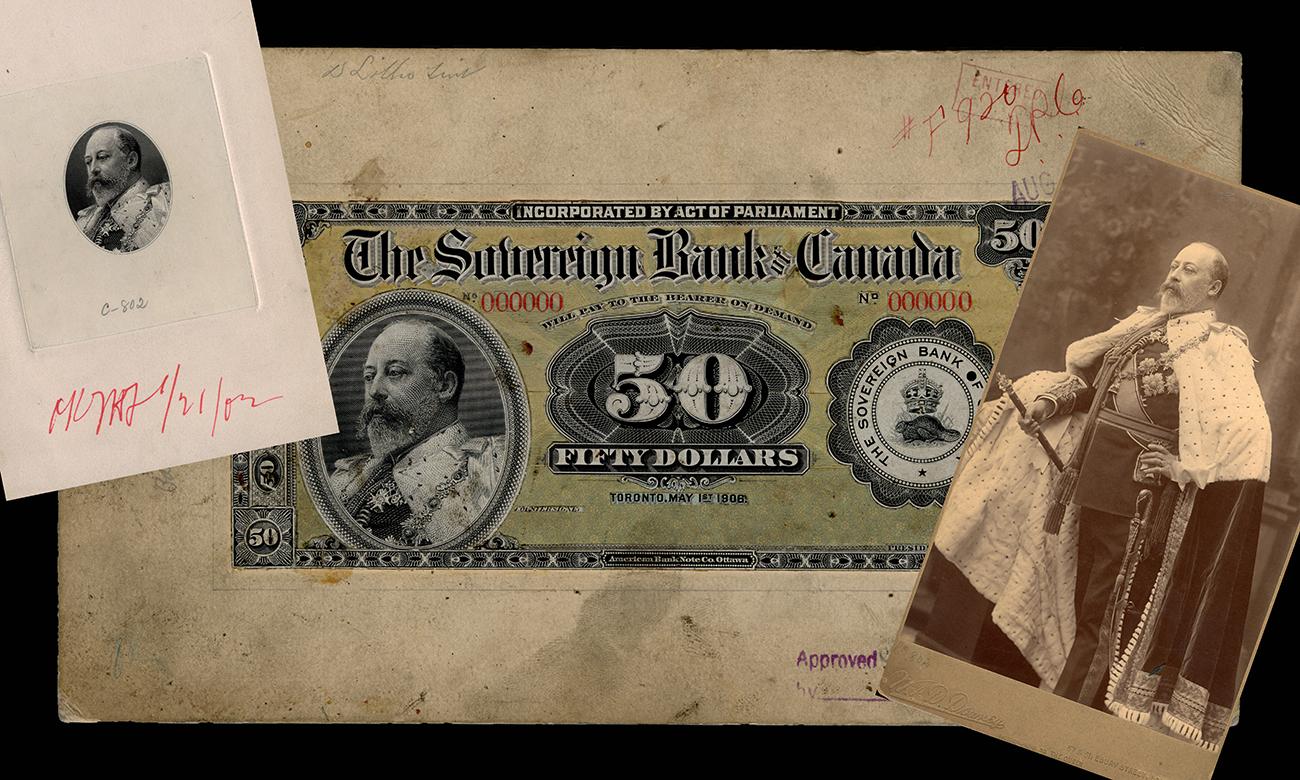

The Barrett-Minardo collection also includes original models from some of the lesser-known Canadian chartered banks: the Bank of New Brunswick, Farmers’ Bank of Rustico, Sovereign Bank of Canada and Banque Internationale du Canada. These models demonstrate the process of designing a bank note where standard printed graphic elements, original portraits and bank inscriptions are combined into a collage that essentially resembles a finished product. With the approval of bank officials, the printing company engraved the new dies and assembled the intaglio elements into a master printing plate to print the notes. The models are works of art to the credit of the engravers that worked at the American Bank Note Company!

Banque Internationale du Canada was a Montreal-based francophone bank. It lasted only a couple of years before being taken over by the Home Bank of Canada in 1913.

Source: 5 dollars, face model, Banque Internationale du Canada, Canada, 1911 | NCC 2023.31.143

The Farmers’ Bank of Rustico from Prince Edward Island was the smallest bank by net worth to have operated in Canada.

Source: 1 dollar, face model, Farmers’ Bank of Rustico, Canada, 1862 | NCC 2023.31.140

These design items for the Bank of New Brunswick’s $5 note show an engraving of the Reversing Falls Bridge in Saint John, NB.

Source: 5 dollars, face model, Bank of New Brunswick, Canada, 1904 | NCC 2023.31.174; 5 dollars, plate proof and artwork, American Bank Note Company, Canada, 1904 | NCC 2023.31.188, NCC 2023.31.186

The Sovereign Bank of Canada entered the Canadian banking scene in a flash and left with a bang eight years later by going bankrupt.

Source: 50 dollars, face model, Sovereign Bank of Canada, 1906 | NCC 2023.31.193; plate proof, American Bank Note Company, 1902 | NCC 2023.31.197; photograph, King Edward VII, W. & D. Downey, United Kingdom, around 1901 | NCC 2023.31.195

But wait, there’s more…

Each year, the National Currency Collection grows by hundreds of artifacts. Showcasing them all would be impossible, but here is a quick glance at a few more treasures acquired in 2023:

The Museum Blog

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.