With the continuing rise in use of e-transfers and electronic payments, people have been predicting the death of the humble cheque for decades. But is it really on its last legs?

In 2021, over 404 million personal and commercial cheques were written in Canada. That’s almost 200 million fewer cheques than in 2019. And it’s less than half of the more than a billion cheques Canadians wrote in 2008. It’s plain to see that the use of cheques as a method of payment has been declining steadily since the invention of Interac and pre-authorized payment plans. Yet, the 2021 stats from Payments Canada give us an unexpected picture:

- number of all non-cash payments: 17 billion

- number of electronic payments: 16.6 billion

- number of cheques written: 404 million

- combined value of all non-cash payments: $10.7 trillion

- value of electronic payments: $7.4 trillion

- value of cheques: $3.28 trillion

Just over 2.4% of all non-cash payments in Canada were made with cheques. Yet those cheques accounted for 30% of the total value paid out. The story all these numbers tell us is that Canadians are writing fewer cheques, but those cheques are for much larger amounts. In fact, the average cheque was for over $8,000.00. This makes sense when you think about the way we pay for things—if you paid rent, bought a vehicle or made a down payment on a new house, then chances are you wrote a personal cheque, or you got a bank draft to make that payment.

When cash was king, cheques took up the slack

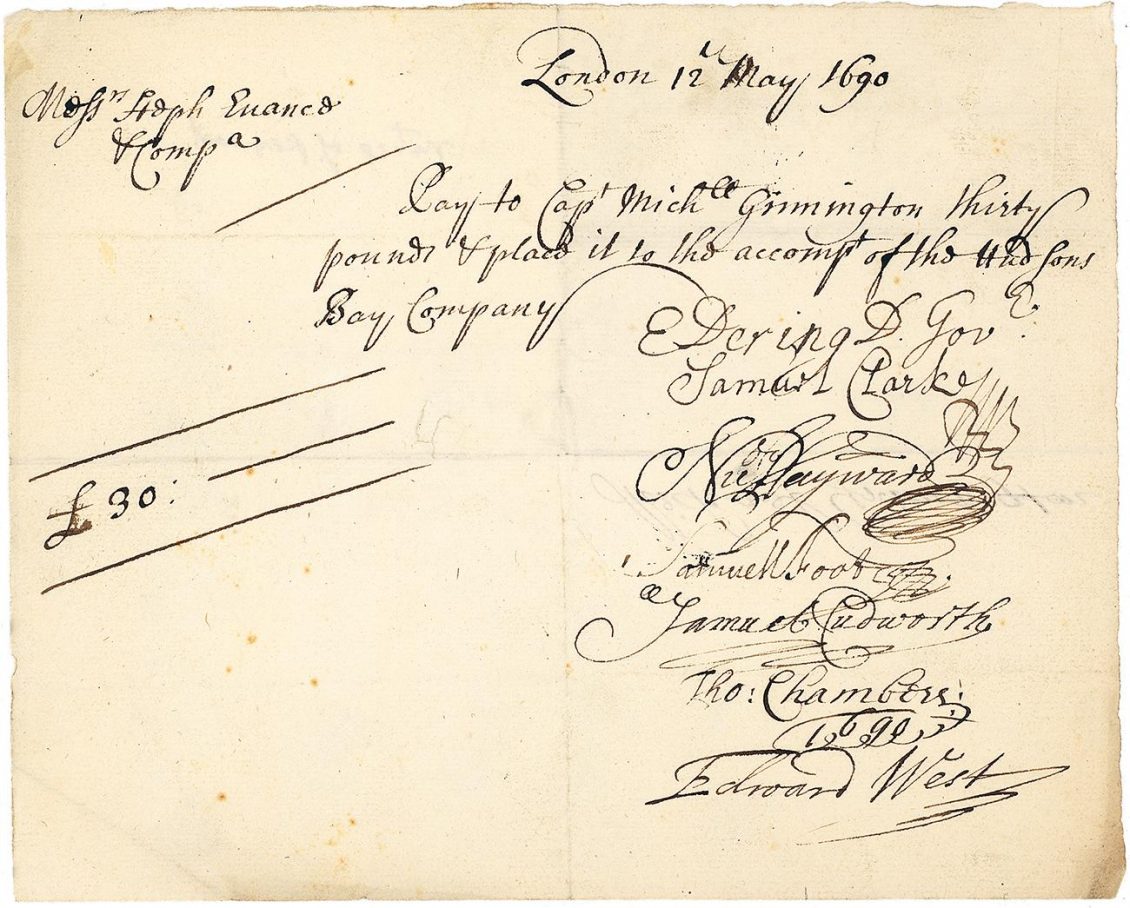

For centuries, when hard currency ruled commercial trade, pay orders such as bills of exchange, bank drafts, promissory notes and cheques made up for the shortage of available coins to make payments. Pieces of paper—either handwritten or formally printed with all the legal language—replaced volumes of gold and silver coins, which were extremely risky to protect and transport. In fact, pay orders were crucial for economic growth around the world all the way up to the age of electronic payments.

A cheque is a written pay order issued and signed by the payer. This order instructs their financial institution (usually a bank) to transfer the amount indicated on the cheque from their account to the person or organization (the payee) who’s name appears on the cheque. Cheques are transferable, which means that the original payee can sign the cheque and give it to another person or organization who can then claim the funds.

Cheques likely evolved from bills of exchange, which were used extensively in trade in Venice and Florence, Italy, starting in the 12th century. These city states were at the crossroads of trade with the Middle East, North Africa, the Indian subcontinent and the Far East. Bills of exchange were payable after a certain period—useful for international trade where time delays had to be considered in travel. Cheques, in contrast, were payable immediately, which was better for use in domestic or local transactions.

Why are they called cheques? The word comes from the game of chess, which in French is échec and refers to the action of putting the king in check. The theory is that cheques helped prevent forgeries because they were attached to stubs (actually called counterfoils) in a cheque book. When writing a cheque, the issuer would enter the details of the cheque on the stub. When the cheque was presented for payment, it was matched with the stub and validated. Then the cheque was cancelled and paid out. Over centuries, cheques became a convenient means of payment in private transactions.

Pay orders and banking history

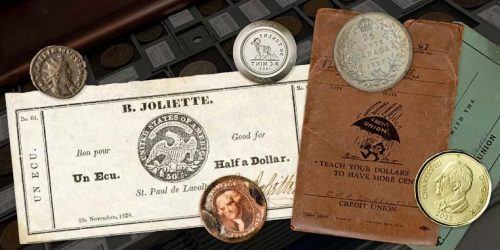

Finding and preserving cheques and other pay orders greatly expands our understanding of the banking industry and uncovers many players—mostly small private bankers from remote communities not serviced by the chartered banks—who would otherwise have fallen into obscurity. Collecting cheques by banking institution is one thing. But the Bank of Canada Museum is actively collecting them by branch—a whole other level!

Private banking: the ‘Hayseed Capitalists’

"Hayseed Capitalists” is the short title of a 1994 PhD thesis by historian and journalist Stephen Thorning (1949-2015) that documents the history of private banking in Ontario. The work records over 150 private bankers operating in small rural towns throughout Ontario between 1850 and 1920. These firms provided essential banking services mainly to farmers, small businesses and retailers who didn’t have access to banks or were reluctant to use their services. Private bankers had accounts at the chartered banks and acted as intermediaries to provide loans and fulfill payments for their clients. By the First World War, private bankers had mostly disappeared after their firms were bought up by bigger banks and turned into branches. Today, many of these firms would be forgotten if not for the cheques that bear their names.

Savings banks and trust companies: a popular choice

Add to the mix of financial institutions the savings banks and trust companies that operated across Canada. Like the private bankers of the late 19th century, these institutions provided essential financial services but could not issue bank notes. To attract clients’ deposits, they offered interest earned on savings or access to a pool of funds for loans or an extension of credit. Established in 1846, the Montreal City and District Savings Bank was the first savings bank in Canada. In 1987 it became Laurentian Bank. The first caisse populaire, founded in 1900 by Alphonse Desjardins of Lévis, Quebec, operated franchises across Quebec and in francophone communities in northern and eastern Ontario. Today the company is known simply as Desjardins. Again, a consolidation of the banking industry saw the merger and acquisitions of dozens of trust companies and savings banks by the Big Six banks that dominate the financial services sector in Canada today (Royal Bank of Canada, BMO Financial Group, TD Bank Group, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Scotiabank and National Bank of Canada). Through the preservation of their cheques, evidence of these financial institutions, which were important in their heyday, has also been preserved.

Other financial institutions: some gone, but not forgotten

Besides the Big Six banks, many other financial institutions provided—and still provide—banking services to millions of Canadians. Some operate as trust companies, credit unions or small regional banks. A few are government-backed banks while others are branches of foreign banks with footholds in Canada. Some of these institutions have since disappeared. These cheques are from less well-known financial institutions that are now gone from the banking landscape.

Apart from the Bank of Canada, no financial institution can issue its own currency. But they have other artifacts that can be preserved to tell their story. The Bank of Canada Museum has been collecting bank cards for over twenty years. It goes to show that more than just traditional cash is available to help us interpret Canada’s monetary and economic history.

Debit card from a foreign bank

The noble role of the humble cheque today

Cheques have been around for centuries. They were the workhorse of the payment system before computers (and are arguably still so today). They were so convenient and flexible that the first bank notes looked like pay orders—similar to a cheque. Before the Second World War, cheques must have been issued and traded daily in the millions, though we don’t know exact numbers. But as consumerism expanded, and access to retail stores grew, paying by cheque at the counter became inconvenient because of the time it took the shopper to write the cheque and the cashier to record and verify the transaction. Yet, cheques are not likely to disappear anytime soon. And while they’re still in use, it’s crucial to preserve them as an element of material culture we can use to trace the history of the banking industry in Canada.

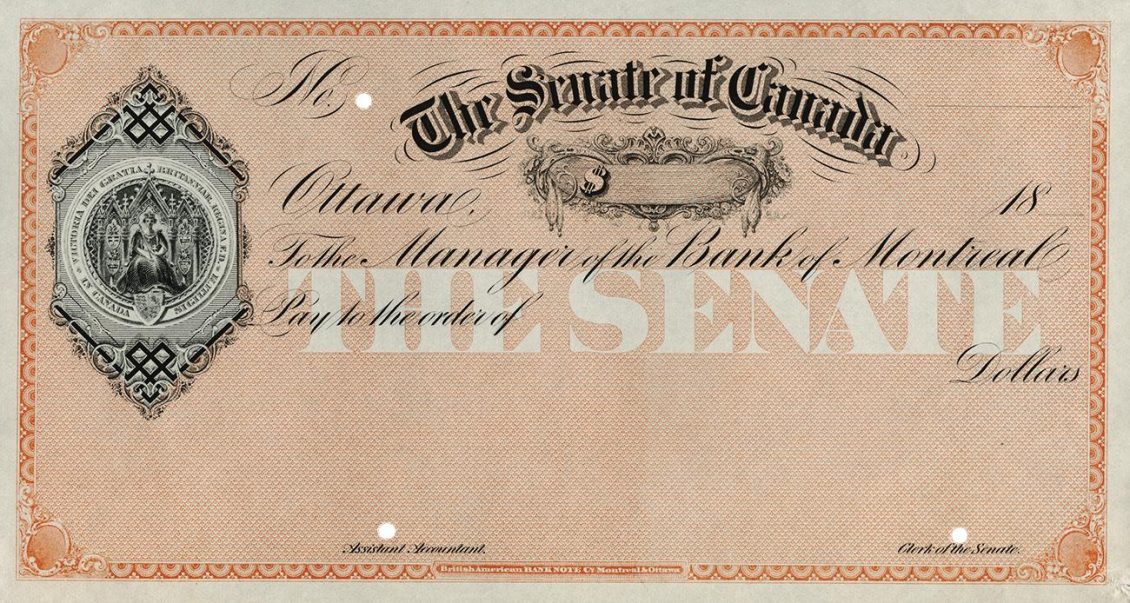

Government departments make millions of benefit payments every year using cheques. This blank cheque from the Senate of Canada was most likely used to pay senators’ expenses and salaries. The cheque features the Great Seal of Canada on the left depicting Queen Victoria on the throne.

Source: Cheque, Senate of Canada, Canada, around 1867 | NCC 2005.127.2

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.

Treaties, money and art

The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art?