A brief history of a cat and mouse relationship

Counterfeiting is a game of responding to new bank note security features. Security printing is a game of anticipating and responding to the threat of counterfeiting. It’s a centuries-old, no-holds-barred rivalry affecting every aspect of a bank note.

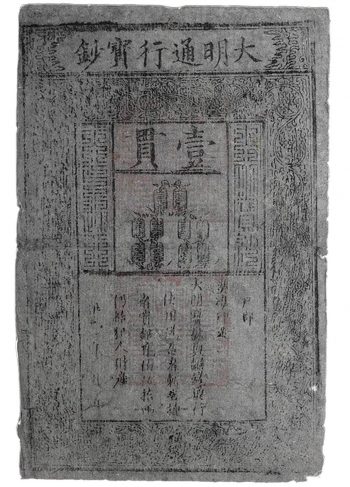

Going medieval on counterfeiters

Back in the 14th century, China’s Ming Dynasty issued some of the world’s earliest paper money. But the emperor’s bureaucrats were no fools. They knew that criminals would already be hard at work trying to copy it. So, each note carried a warning:

Those using counterfeit notes will be executed. Informants will receive 250 liang of silver and the entire property of the criminal.”

There is no record of how well this warning worked, but we can safely assume there were no repeat offenders. Paper money came and went for the next few hundred years, not becoming a regular feature of Western economies until the 18th century.

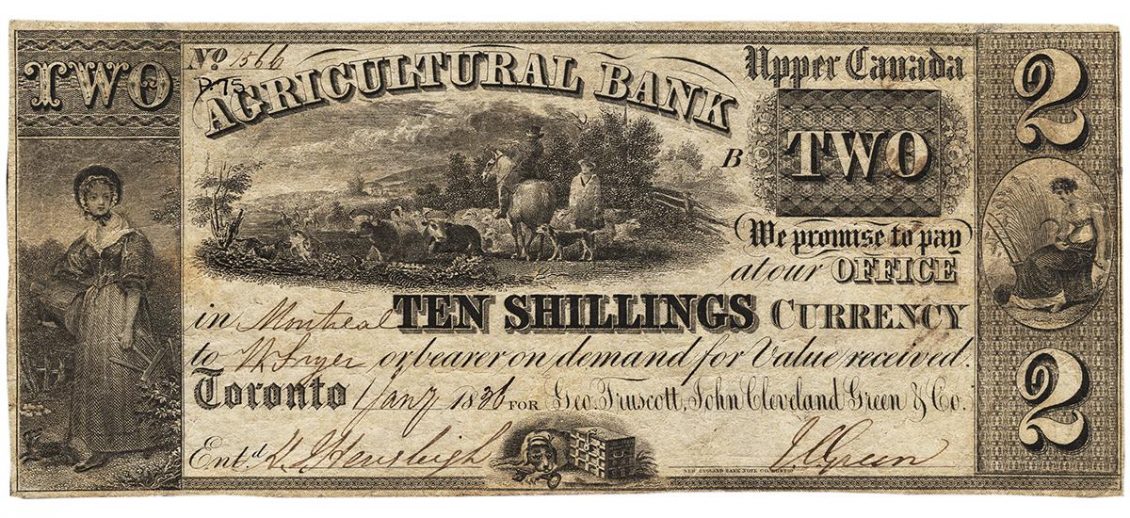

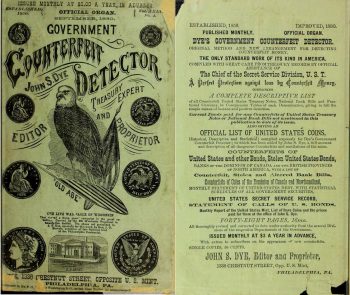

The 19th century: A counterfeiter’s playground

The banking industry was booming in early 19th century North America. It was also essentially unregulated—a golden age both of counterfeiting and security printing innovation.

Security printers met counterfeiters’ challenges with high-quality papers, later adding coloured dots (planchettes) and watermarks. When fraudsters began reproducing notes using photographic processes, printers introduced coloured inks. But counterfeiters removed the coloured ink from real notes, reproduced the black portions photographically and later applied the coloured parts to their fakes with another process. This particular battle resulted in notes printed with a green ink nearly impossible to remove—and the American “greenback” was born.

But high-quality engraving was still a key defence for security printers. Sir Isaac Newton (of gravity fame) was the master of the British Royal Mint for nearly 30 years. He once said that “good graving is still the best security.” However, in the 19th century there were plenty of highly skilled engravers around—and not all were honest.

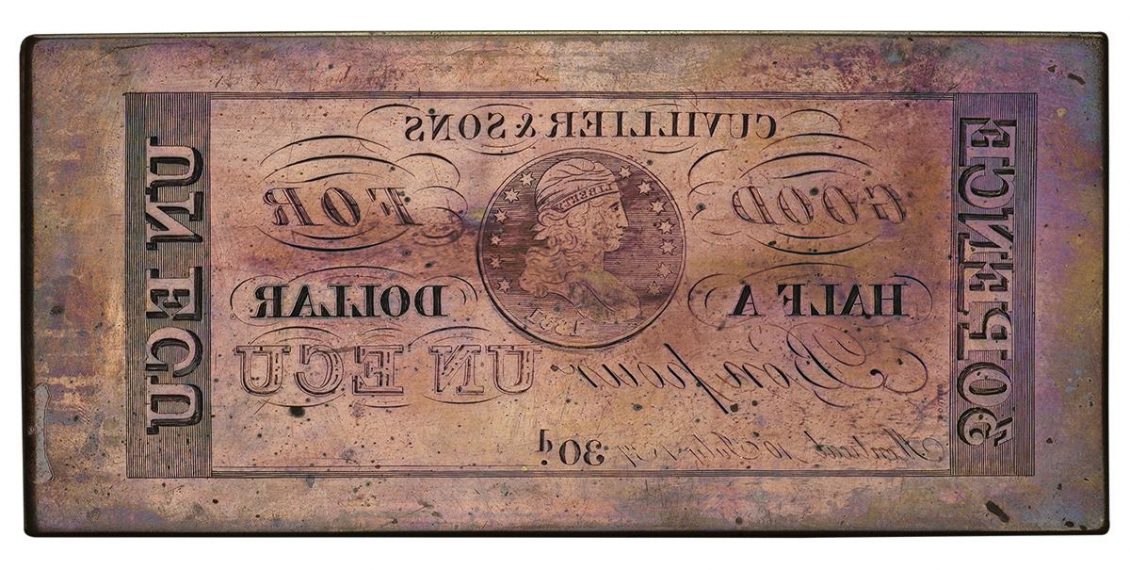

Intaglio printing simplified: An artist would hand-engrave a reversed design into metal. Ink was pushed into the cuts and wiped from the blank areas. The plate was pressed against paper, resulting in raised printing you can feel.

Source: 1 ecu, printing plate, Cuvillier & Sons, Canada, 1837 | NCC 1974.263.7

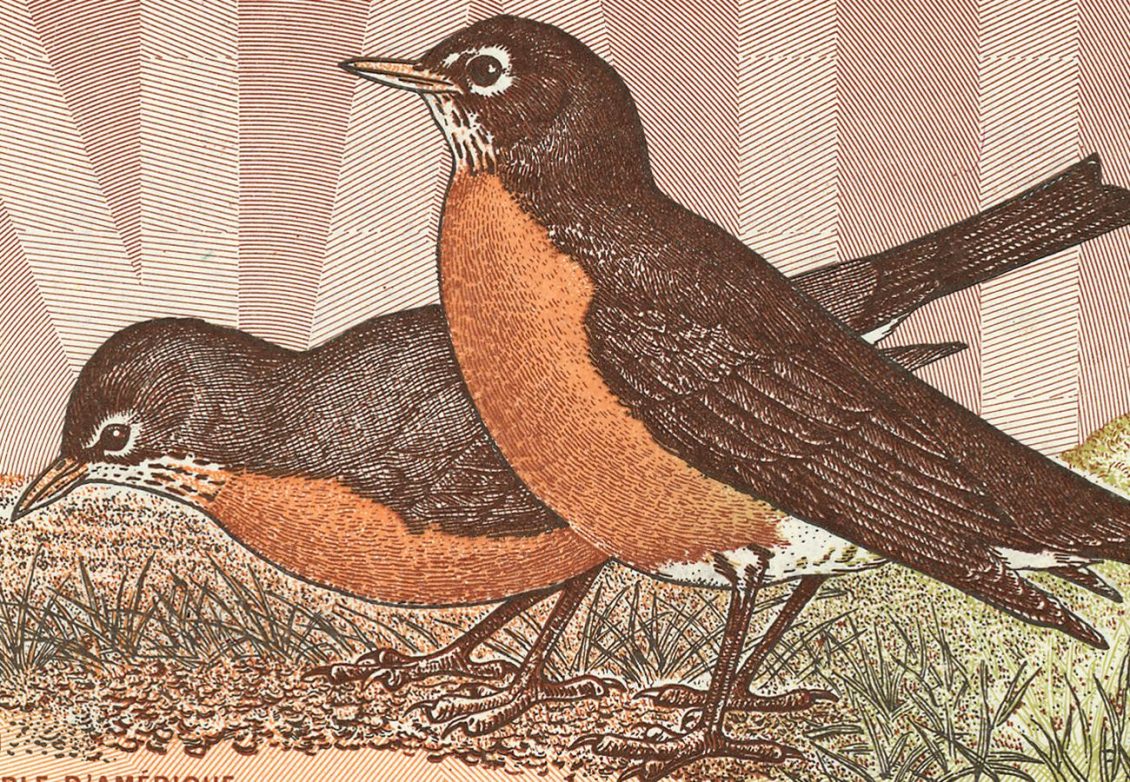

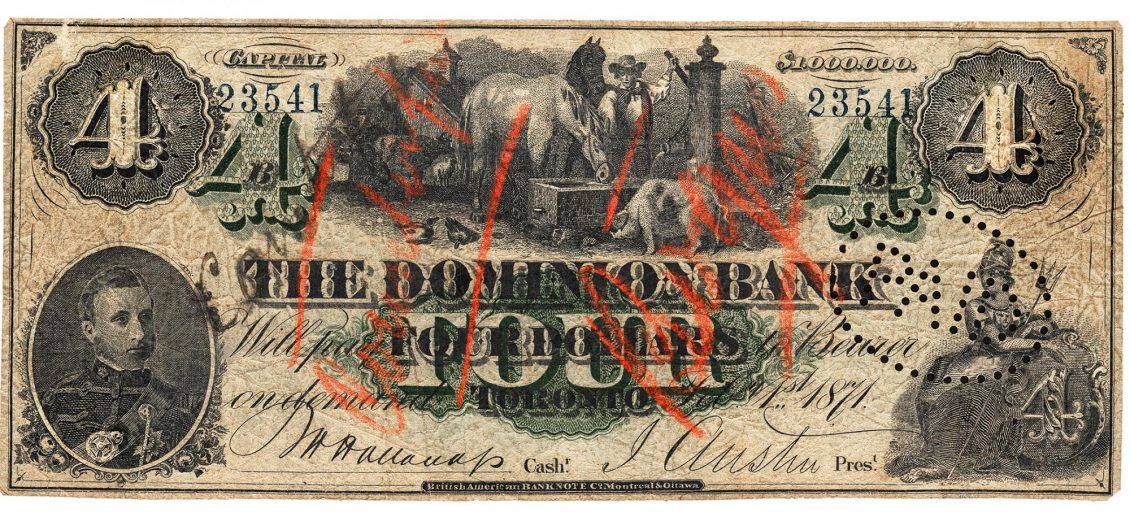

This note is by master counterfeiter Edwin Johnson. His skills were as good or better than legitimate security engravers of his day.

Source: 4 dollars, forgery, Dominion Bank, Canada 1871 | NCC 1967.50.2

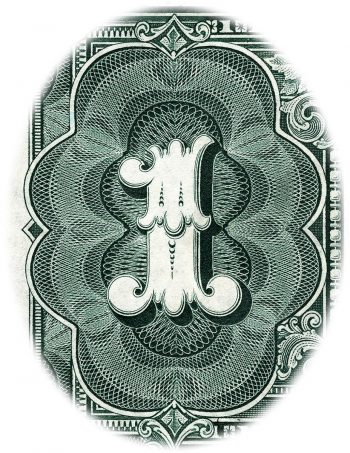

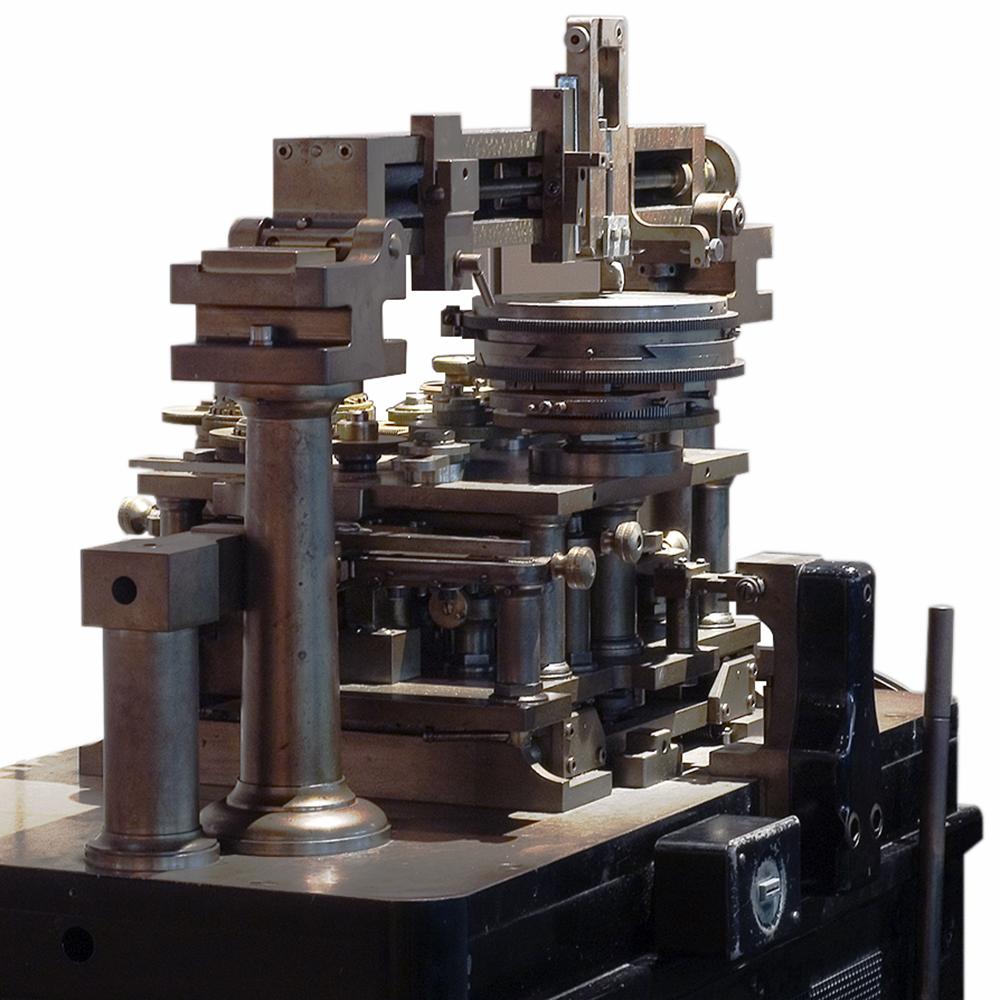

Guilloche: The security printer’s trump card

What characterized older bank notes also made them more secure: guilloche (pronounced ghee-osh) patterns. A machine called a geometric lathe produced guilloche. It repeatedly rotated and rocked a metal plate against a cutting tool, subtly changing with each movement. The patterns generated were geometric, like those of a Spirograph but a whole lot more complicated. Reproducing an existing guilloche pattern with another machine (or even the same machine) was nearly impossible, so a counterfeiter would need to recreate the pattern by hand. A daunting task.

The late 20th century: A heyday of innovation

After the 19th century’s burst of innovation, things slowed down. Through the Bank of Canada’s first three series of notes, most counterfeit protection came from simply designing new bills. But heading into the 1960s, counterfeiting had again become a serious problem. The time had come to get innovative—and more colourful.

In 1970, a new and extraordinary Canadian $20 bill appeared. It had multiple shades of green with gradually fading magenta overtones. The coat of arms was brilliantly coloured, intricate patterns filled blank areas, and whimsical guilloche patterns twisted and drifted elegantly around the denominations. It was so unlike previous notes that some Canadians doubted it was real money.

The subtle fading of colour could only be done easily with lithography. This note heralded the beginning of the Bank of Canada’s extensive use of that printing process.

Source: 20 dollars, Canada, 1969 | NCC 1970.166.1

The striking appearance of the Scenes of Canada notes was a direct response to security threats. If simple monotone notes were easy to copy, then a note of great detail and colour should stop counterfeiters in their tracks. And it did. But it wouldn’t for long. A dangerous new counterfeiting tool was already on its way: the colour photocopier. It would make short work of replicating colour and detail. So, before it had even issued all of the Scenes notes, the Bank began exploring a new approach. This is a case of security printing anticipating a threat, not just responding to one.

Back to simplicity

The response to modern imaging technology was, oddly, a step back to the simplicity of the 1954 bank note series. It was expected that any tell-tale flaws generated by photocopying might be difficult to see in an elaborate or busy design. Instead, a simple, clean design with lots of open space was proposed. But those seemingly empty spaces were full of a new sort of feature: microprinted words and lines. And the lines were the key. Fine and closely spaced, they appeared as blank, toned areas. But when scanned or photocopied, curious waves—called moiré patterns—emerged.

A new bag of tricks

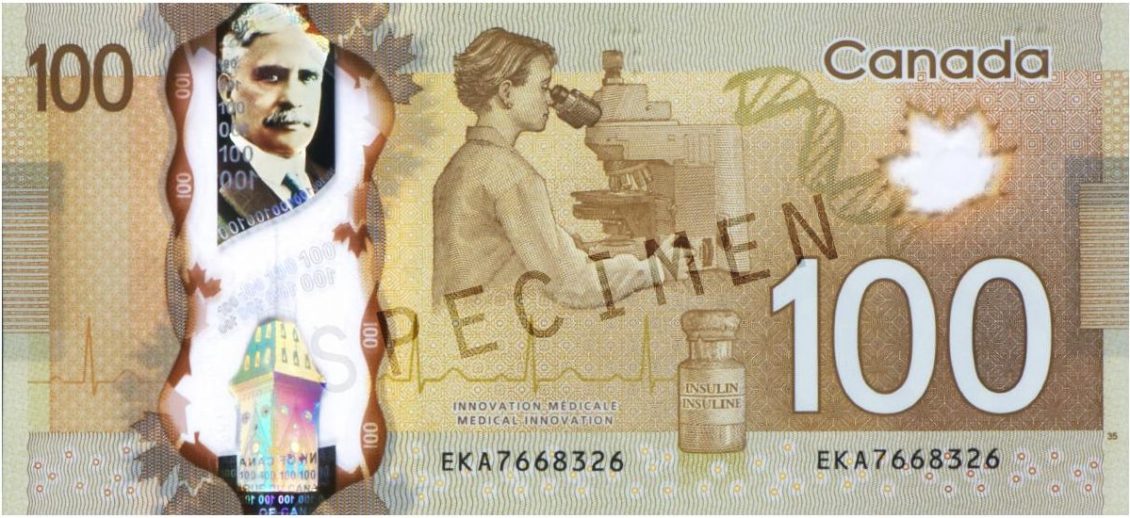

The Birds of Canada series was also the first in the world to feature what is called an optical security device. It is a metallic patch that changes colour when tilted and can’t be reproduced by any imaging process. Similar technology appeared later in the Canadian Journey series as an elegant holographic stripe that changed colour as you shifted the note. It was more sophisticated—and more beautiful—than the patch.

The Journey series was an anti-counterfeiting minefield. Random threads were embedded throughout the paper and ghost images of the portraits haunted seemingly blank spaces. Microprinting and patterning carpeted nearly every centimetre not occupied by an image. One feature was visible only under ultraviolet light. Lastly, a curious half-completed number was printed on each side. Viewed against a bright light, the number completed itself if the back and front were exactly aligned—a near impossible printing task for your average counterfeiter.

The 21st century: The era of digital technology

And what about modern scanners and image editing software? The Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group is a global body that has developed a system—adopted by software producers worldwide— to prevent unauthorized digital reproductions of bank notes. If you were to try to scan a Canadian bank note, the software would recognize it and refuse to scan. Image editing software such as Photoshop will recognize photographs of our notes and refuse to even open the image file.

Plastic is the new paper

The Reserve Bank of Australia introduced polymer bank notes to the world in 1988. With clear windows and striking colours, the notes were a bit of a sensation. Canada followed suit in 2011. Both durable and recyclable, polymer itself is also an anti-counterfeiting tool. It requires special inks and coatings and is next to impossible for a counterfeiter to obtain. In addition to the substrate, our current notes are as rich with security features as any previous series.

Do you have a counterfeit?

Here are four ways you can check if the Canadian notes in your pocket are real or fake:

- Inspect the window: Do the tiny numbers in it match the denomination? Does the portrait match the main portrait?

- Tilt the note: Do the images in the window change colour?

- Run your fingers over the main portrait: Can you feel raised ink?

- Hold the maple leaf window to your eye and look at a small, bright light source such as a powerful LED: Do you see tiny numbers?

Any no’s? Take the note to the police, or to your bank. Don’t spend it!

The stats speak

Since the introduction of the Canadian Journey and Frontiers series, counterfeiting has dropped to negligible numbers—in one case from a peak of over 300,000 notes in one year down to double digits. Check out the Bank’s interactive statistical graphs on counterfeiting.

Centuries-old intaglio printing still can’t be believably faked by counterfeiters. So, though chock full of modern innovations, the vertical $10 note includes some features, such as the portrait, that are engraved.

Source: 10 dollars, Canada, 2018 | NCC 2018.75.1

What comes next

Understandably, we can’t say much about the innovations that the Bank of Canada is researching. A whole team of engineers, chemists and other specialists are constantly testing new features. But nobody works in isolation these days—it’s a collaborative, global market of new ideas and technologies in this game of anticipation and response.

The Museum Blog

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.