The If Day propaganda notes of the Second World War

Imagine waking up one morning to learn that your city is under military occupation by a foreign enemy—and the enemy’s money has become yours.

Winnipeg occupied

Winnipeg is famous for its cold winter weather. But on the morning of February 19, 1942, Winnipeggers were not concerned about how cold it was at Portage and Main. They woke up to the wailing of air-raid sirens and a total blackout. Winnipeg was being invaded! About 3,800 German-uniformed soldiers had taken over the city.

But Germany never invaded Canada. The extent of the military threat in Canada during the Second World War was the sighting of German U-boats in the St. Lawrence River. No German soldier ever set foot on Canadian soil as part of an invading force. Yet, on that day, Winnipeggers would have begged to differ.

Welcome to “Himmlerstadt”

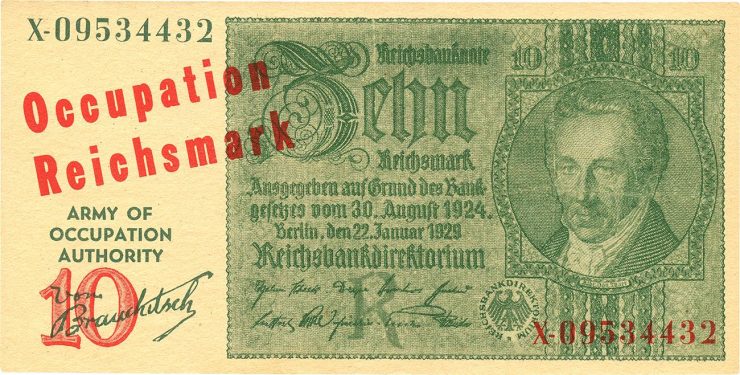

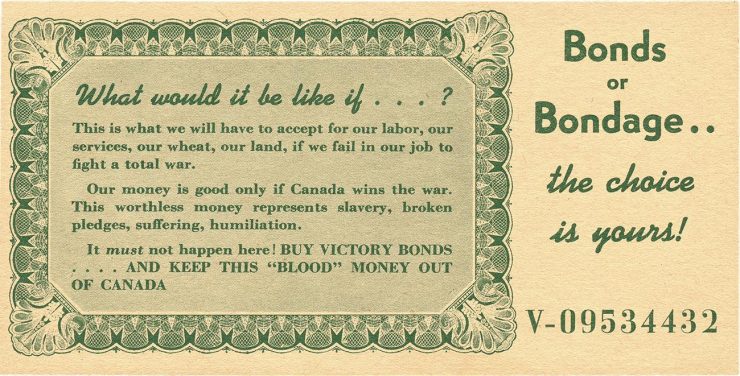

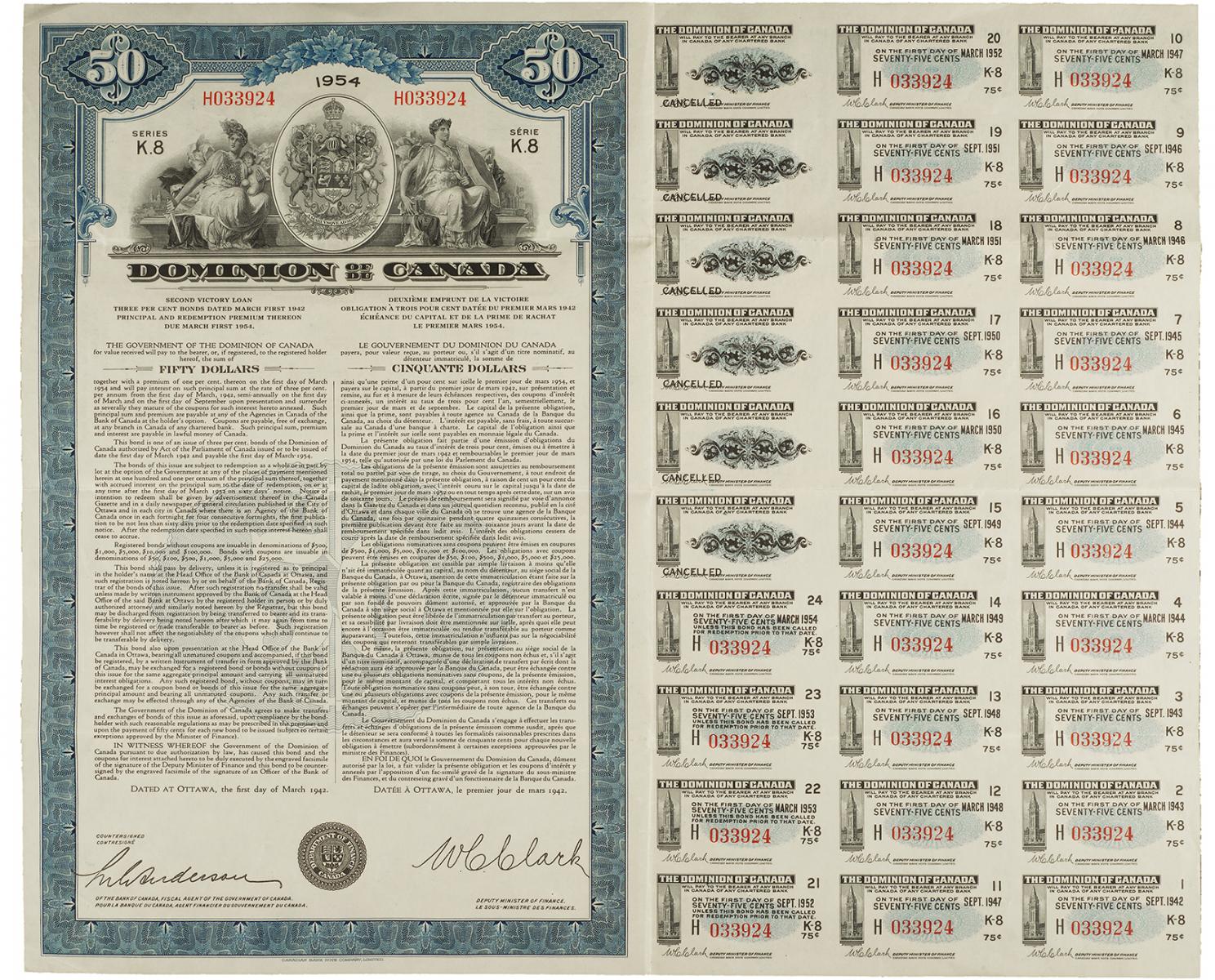

It was a scary scene of German occupation. Wehrmacht tanks patrolled the streets, and the Luftwaffe controlled the skies. In true blitzkrieg fashion, invasion and occupation were swift. Within a few hours, the city of Winnipeg surrendered and was renamed “Himmlerstadt” (Himmler City). The invaders took over local radio stations and newspapers to control information. Propaganda slogans of “everything is kaput” dominated the headlines. Checkpoints were set up to control movement in the city. People on the street were randomly stopped and searched. Some were arrested and imprisoned in an internment camp set up in Lower Fort Garry. Even German marks replaced Canadian dollars in circulation—in the form of so-called If Day propaganda notes.

A mock invasion to promote war bonds

Media coverage of the event was widespread, with major Canadian and US newspapers and newsreel companies filing stories. Many readers and viewers thought it was real. But as news continued to unfold, they learned that the event was a mock invasion. The 3,800 invaders were Canadians dressed in German uniforms, all part of an elaborate scheme to demonstrate what a German invasion could look like. Government officials at all levels were aware of the plot. The National War Finance Committee, which was responsible for financing the Canadian war effort, orchestrated the mock invasion through its Winnipeg chapter. It was all to promote the sale of Victory Loan bonds.

Bonds to fund the war

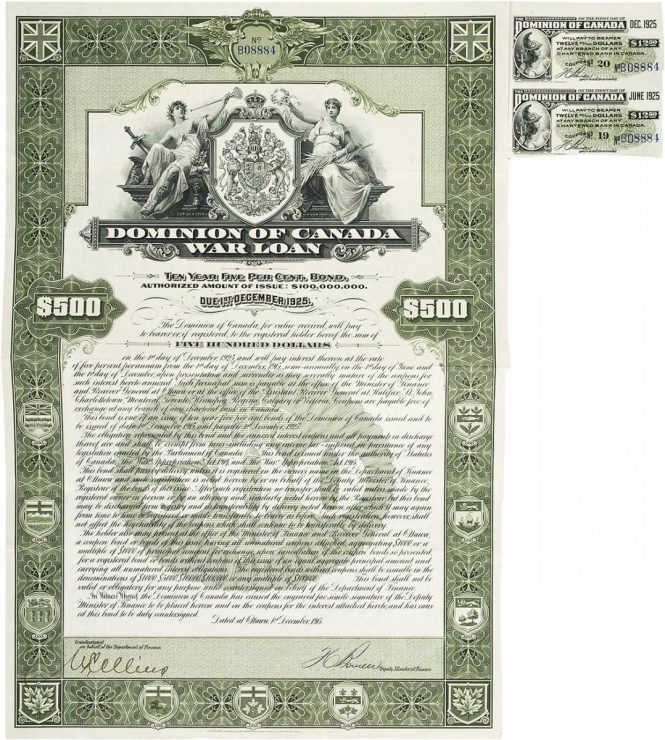

Bonds to raise money for the war effort were initially issued in Canada during the First World War. The goal of the Dominion of Canada’s government was to raise $50 million for the war effort. Canadians rose to the challenge and oversubscribed to the tune of $100 million. The excess funds were loaned to the British government to purchase supplies such as munitions and food.

The success of this—and later bond offerings—prompted the government to make bond drives a regular feature of its initiative to raise funds in the Second World War. In encouraging the sale of Victory Loan bonds, the occupation of Winnipeg was a daring, yet very effective stunt.

The success of Victory Loan bonds

The bond campaigns of the First World War were so successful that the Dominion Government carried out 11 campaigns for its Victory bonds during the Second World War. Nationwide initiatives began in 1940, managed by the National War Savings Committee. After 1942, the National War Finance Committee managed these initiatives, with the Bank of Canada responsible for issuing and redeeming bonds and certificates.

A total of $11.8 billion was raised from the Victory Loans, with both individuals and corporations purchasing bonds. The If Day mock invasion undoubtedly influenced many Winnipeggers to buy bonds. On that day alone, $3.5 million worth of bonds were subscribed. This contributed to the $843.2 million raised during the second Victory Loan campaign, which began on March 1, 1942.

In its capacity as agent for the Dominion Government in respect of the management of the public debt, it became the duty of the Bank to arrange for the issue and redemption of Certificates."

Bank of Canada Annual Report, 1940

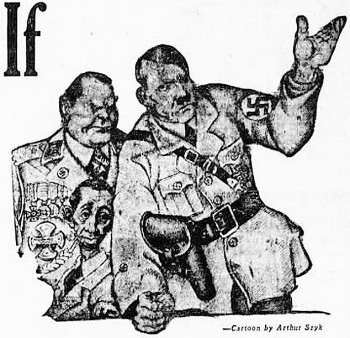

Money, war and propaganda

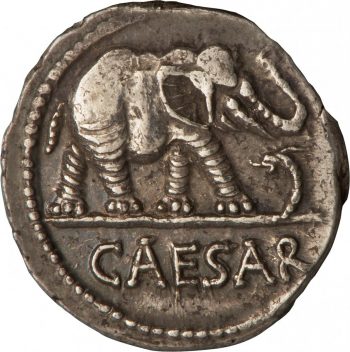

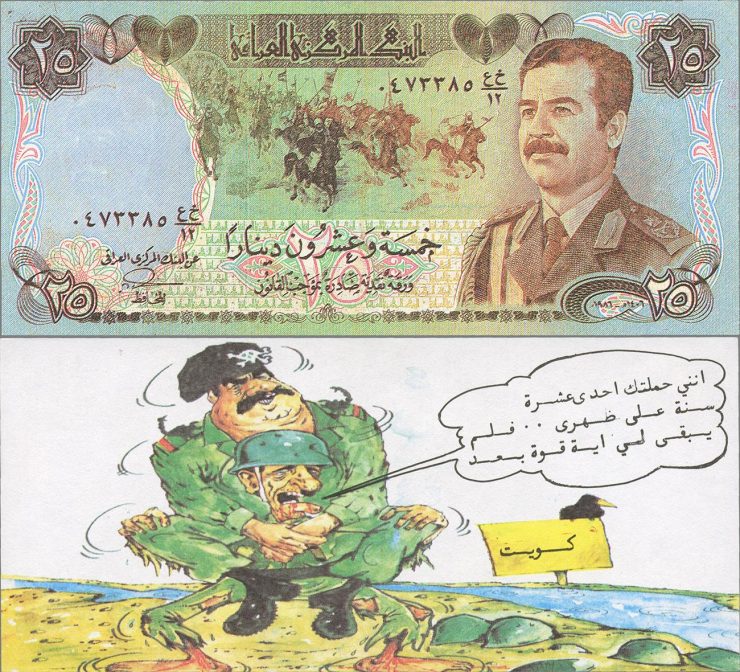

Propaganda in times of war is nothing new. And throughout history, money has served as a form of propaganda. Julius Caesar’s famous Roman silver denarius, showing an elephant trampling a serpent, was believed to be pure propaganda to tout his military victory over the Gaulish people. During many modern military campaigns, armed forces printed leaflets in the style of paper money. Each note offered a message of amnesty—if the troops surrendered. Some parties issued propaganda notes to defame their adversary and its people. Propaganda notes were an effective tool for influencing people to either give up or, as in the case of the If Day notes, help support the war effort.

This propaganda note simulates an Iraqi 25-dinar note, with Saddam Hussein on the front and a caricature of Saddam being carried on the shoulders of an Iraqi soldier on the back. The message in Arabic reads, “I have carried you for 11 years. I have no strength to carry you anymore." These notes were airdropped over cities in Iraq during Operation Desert Storm.

Source: Propaganda note, US Army Psychological Operations Group, United States, 1990 | NCC 2019.69.90

Winnipeg liberated

Although Winnipeg was never actually occupied, Winnipeggers spent a day experiencing what many Europeans had been going through every day since the outbreak of the war. The success of the If Day mock invasion was so remarkable that other North American cities conducted their own bond drives to raise funds for the war. The If Day notes even found their way to Vancouver, British Columbia, to promote the sale of Victory bonds there. The extreme measure taken by the National War Finance Committee—to simulate an invasion to scare people into buying Victory Loan bonds—was rather audacious. But it certainly drove the message home to all Canadians that they should support the war effort in any way possible.

The Museum Blog

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.