Bank of Canada notes have been in our wallets for nearly 90 years. The first series was designed to inspire confidence in a promising future.

Notes for an era of economic recovery

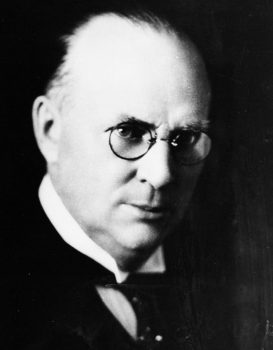

Between 1929 and 1934, Canada was in the midst of the Great Depression. Demand for Canadian exports fell, and unemployment rose to staggering new levels. During this time, the government of then-Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett passed the Bank of Canada Act, paving the way for the creation of Canada’s central bank. Among its many responsibilities, the Bank of Canada became the sole issuer of Canadian bank notes, the first of which began circulating on March 11, 1935. The design of these notes can tell us a lot about Canadian society and the country’s identity at the time. The notes can also show how the new central bank presented a road map for Canada’s economic recovery.

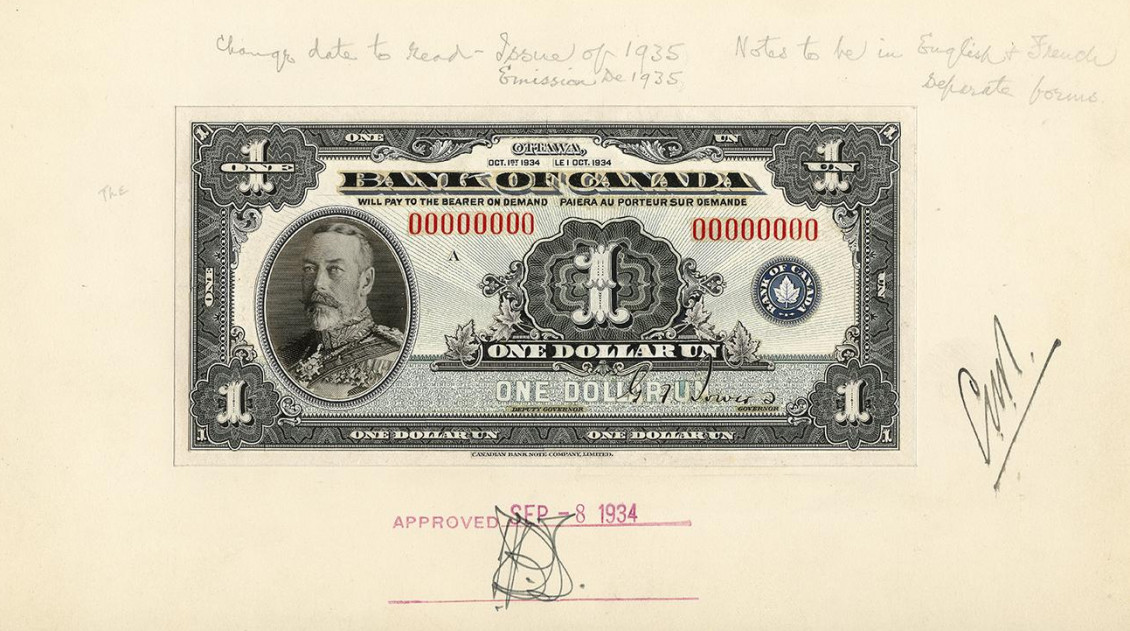

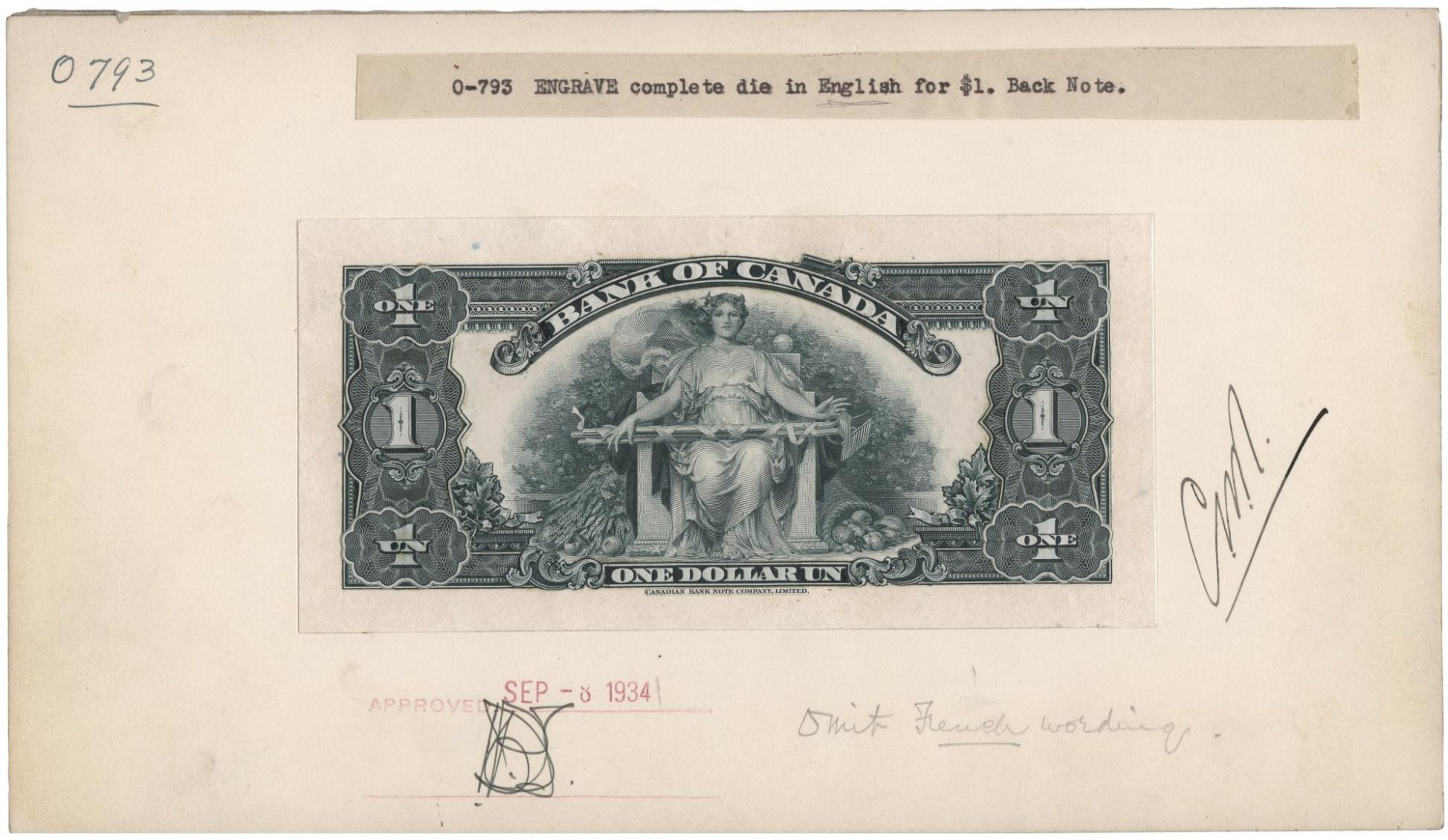

Designing new Canadian notes

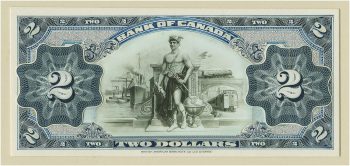

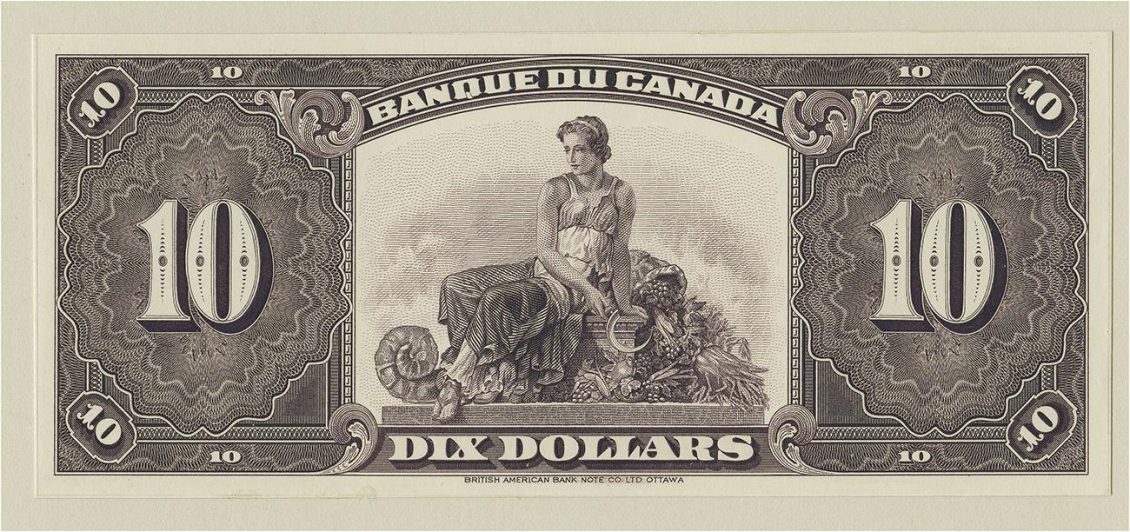

After the government released a tender for the design of its new bank notes in July 1934, two printing companies submitted proposals: the British American Bank Note Company (BABN) and the Canadian Bank Note Company (CBN), who worked closely with its parent company the American Bank Note Company. The Minister of Finance decided to work with both, awarding a contract for the design and production of the $1, $20, $50, $100, $500 and $1,000 notes to CBN, while giving BABN responsibility for the $2, $5 and $10 notes.

Richard Bedford Bennett was elected Prime Minister of Canada in August 1930, succeeding William Lyon Mackenzie King. He was voted out after only one term, largely due to his lacklustre response to the Great Depression.

Source: Hon. R. B. Bennett, Prime Minister of Canada, photograph, 1930–35 | Library and Archives Canada e999902210-u

The 1935 bank note series has several distinguishing features. It is the only series of Bank of Canada notes to:

- print separate English and French notes

- include a $25 bill

The Bank chose the distinctive $25 denomination for a commemorative note marking King George V’s silver jubilee. The portraits on the notes feature members of the Royal Family and two Canadian prime ministers. For the designs on the backs of the notes, both CBN and BABN brought together imagery from stock catalogues filled with engraved vignettes and other graphic elements. Though the printing companies directed the design process, the Minister of Finance, a deputy or then-Bank of Canada Governor Graham Towers provided the final approval of the notes’ designs.

The Canadian Bank Note Company used this stock vignette from its parent company to create a model of the $5 note. But the Minister of Finance decided that the British American Bank Note Company would design the $5, so this vignette was never used.

Source: American Bank Note Company, 5 dollars, proof, back vignette, 1934 | NCC 1990.43.110

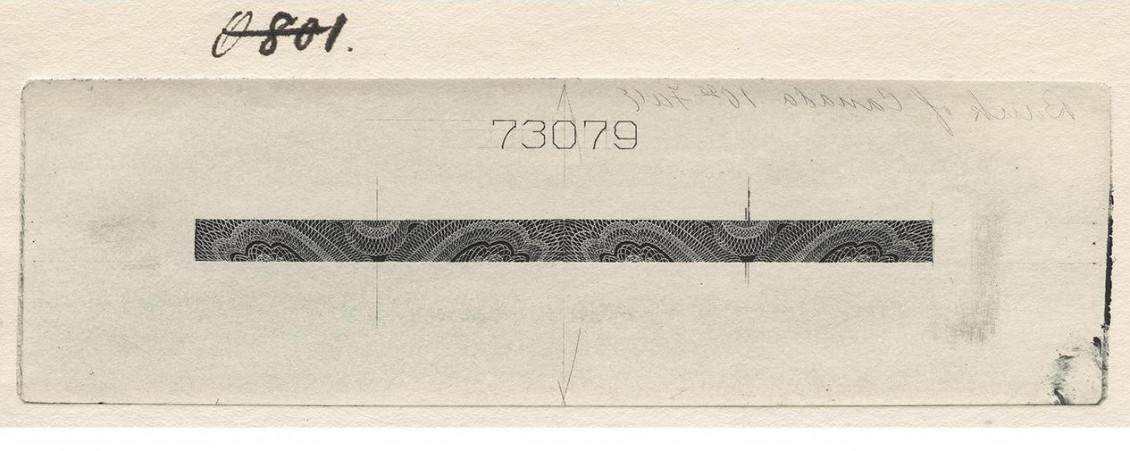

Throughout the series, the counters (representing the denomination of the note) and decorative elements of each note are slightly different. This is one of many $10 counters that CBN could have chosen for its design.

Source: American Bank Note Company, 10 dollars, proof, counter, 1934 | NCC 1990.43.66

The anatomy of a bank note

A bank note’s appearance is critical to establishing trust between the currency issuer and user. For a bank note to work as intended, it must look like a bank note. Individuals expect their notes to have:

- a portrait

- a clearly marked denomination, represented in a “counter”

- the name of the issuer

- recognizable imagery

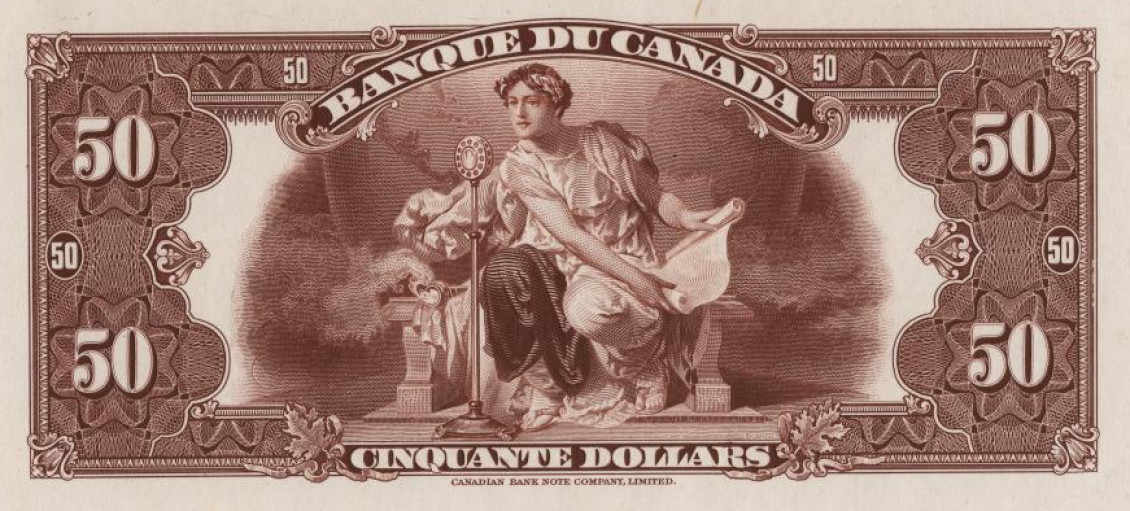

Accordingly, each of these elements was given careful consideration during the design process for the Bank of Canada’s 1935 notes. Though the vignettes are of modern subjects—for example, “modern inventions” on the $50 note—these subjects are represented by classical allegorical figures dressed in Greek or Roman robes.

The discrepancy between the classical style of the vignettes and their modern subject matter is especially striking on the $50 note. A female figure draped in Grecian robes and wearing a laurel crown prepares to speak into a microphone.

Source: Canadian Bank Note Company, 50 dollars, proof | NCC 1990.43.169

Iconography and Canadian identity

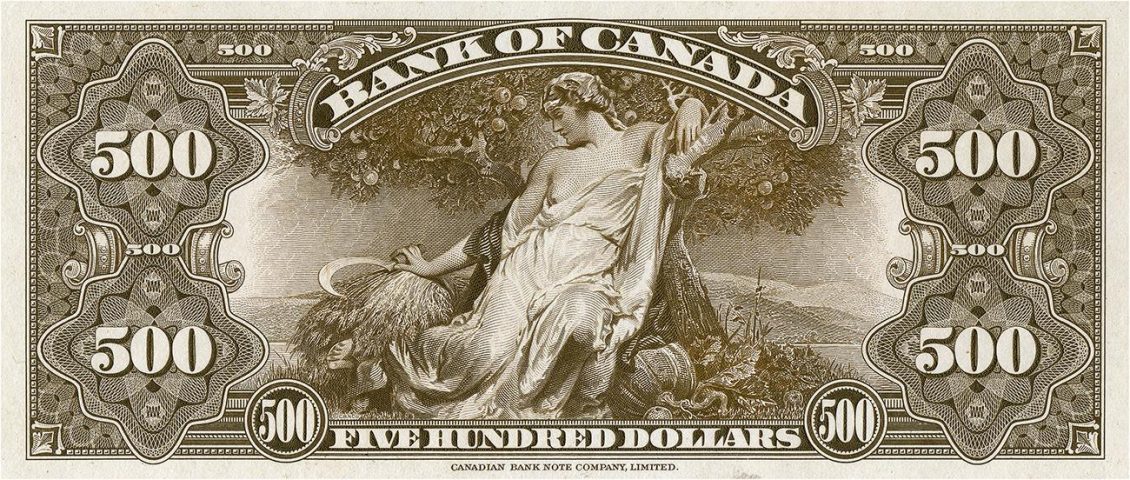

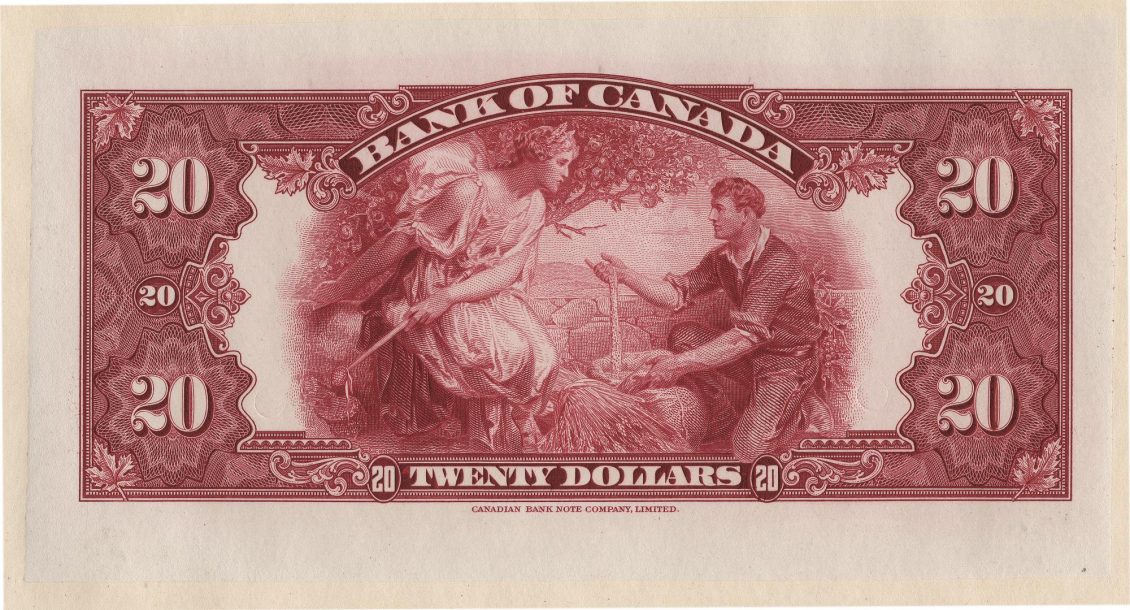

The Royal portraits on 8 of the 10 denominations affirm Canada’s ties to the British Empire. But the back vignettes highlight the country’s natural resources and industries. They position Canada and its economy as a place of innovation and technological advancement. The subjects of the back vignettes provided a vision of Canada as a modern industrial economy, poised to recover from the Great Depression—a recovery that the country’s new central bank would lead. By including images related to industry, innovation and natural resources, the central bank signalled that Canada had the necessary skills and assets to make a strong recovery.

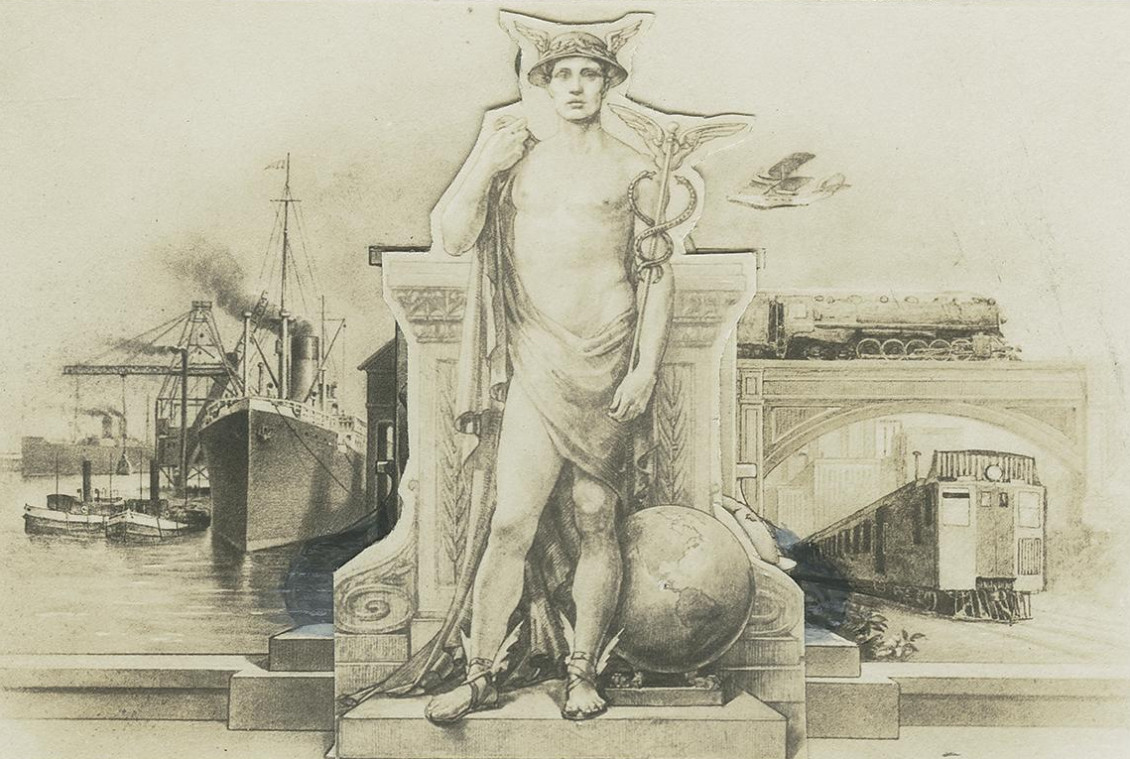

For the transportation allegory on the $5 note, British American Bank Note Company combined two stock vignettes: the train and ship from one and the Mercury figure from another. You can see both pasted together here.

Source: British American Bank Note Company, 5 dollars, drawing, 1934 | NCC 1976.212.18

Images of industry

So what exactly can these images tell us about Canada’s economy and culture in the 1930s? At that time, farming products made up 48% of Canadian exports, so naturally 4 of the 10 notes refer to agriculture, including images of produce, grain, fruit trees and farming tools.

But the Depression hit the industry hard: the collapse of international trade combined with successive years of crop failures due to droughts, hailstorms and pests battered the grain-producing Prairie provinces in the early 1930s. Within that context, the allegory of fertility on back of the $500 is forward-looking and maybe even a little hopeful.

The dry belt is an area of southwestern Saskatchewan that the government opened to farming in 1905. Drought and bad crops in the years leading up to the Depression compounded the impact of the economic downturn.

Source: Saskatchewan dry belt during the Depression, photograph, 1930–34 | Library and Archives Canada e010963445

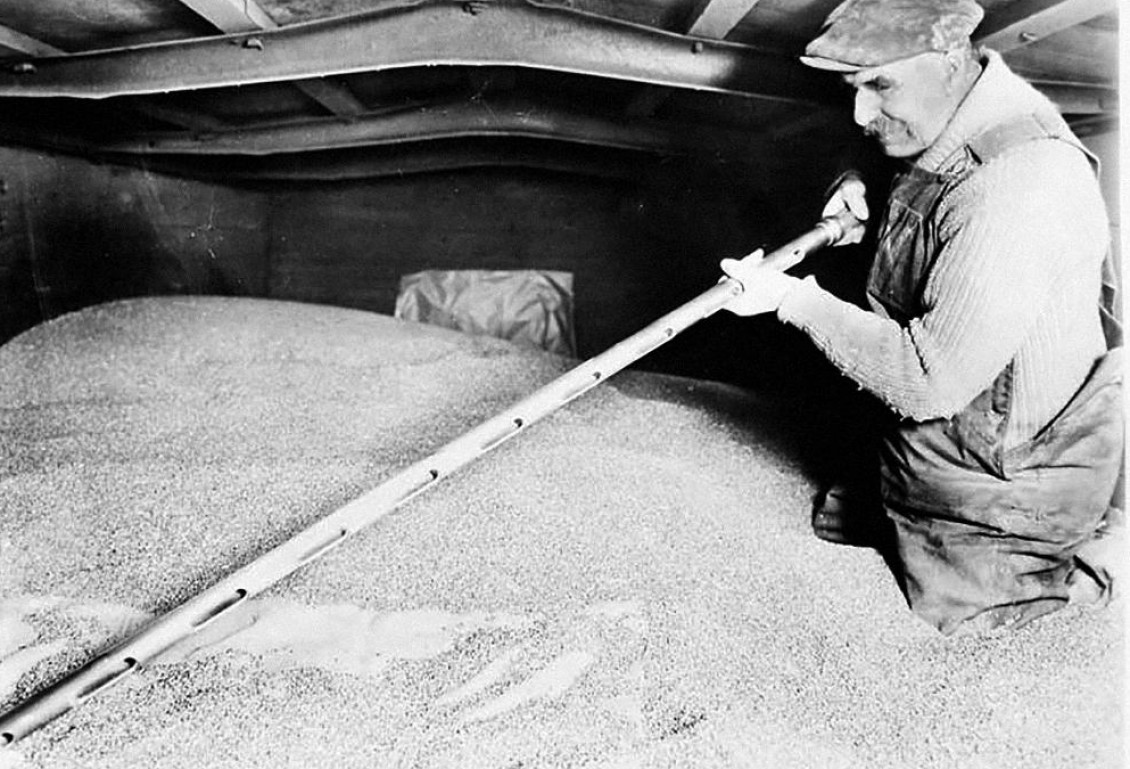

A healthy agriculture industry was key to Canada’s economic recovery. To that end, Prime Minister Bennett created the Canadian Wheat Board in 1935 to stabilize commodity prices and regulate quality. The organization became the primary buyer and seller of Canadian wheat and barley. The “testing the grain” allegory on the $20 note shows a man presenting a bushel of grain to a seated figure. Whether by coincidence or not, the image subtly references this key development in the industry.

The Canadian Wheat Board was established in 1935, but government regulation of the industry dates back to 1917 with the establishment of the Board of Grain Supervisors of Canada.

Source: Taking samples of grain from a boxcar at the Canadian Government Grain Elevator, photograph, c. 1920–30 | Library and Archives Canada a802184

The imagery on the notes refers not only to Canadian industries themselves but also to people’s role in the economy. The vignettes representing “electric power” (on the $5 note) and “commerce and industry” (on the $100 note) superimpose male allegorical figures against two landscapes: a natural one and an industrial one, respectively. Despite their different settings, the compositions of these images send a similar message: that humans (or at least, men) exert control over their world. They emphasize the role of the individual and of hard work in Canada’s economic recovery.

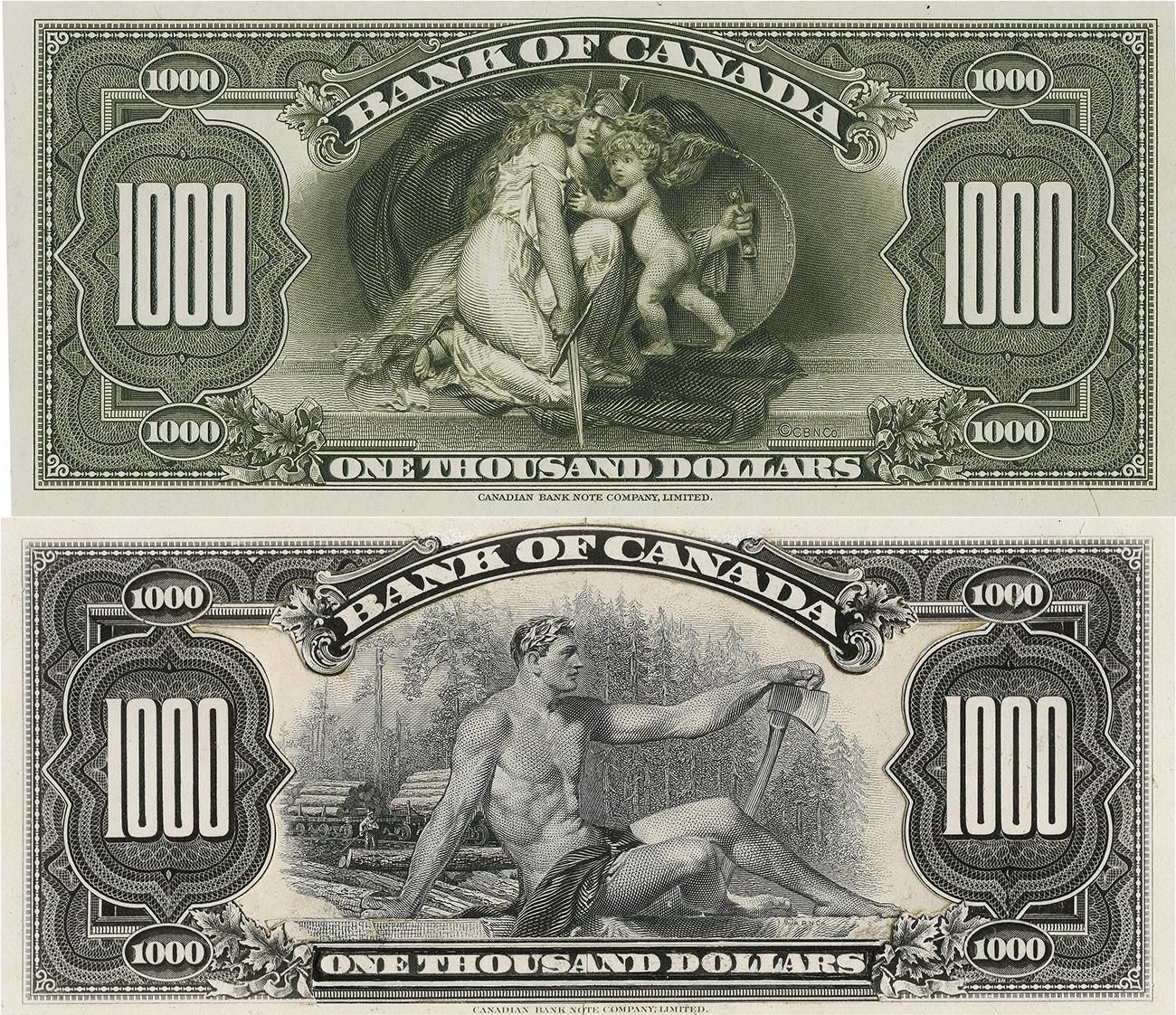

The vignette chosen for the $1,000 note, “security,” most explicitly refers to the Bank of Canada’s role as the country’s new central bank. Along with the issuance of bank notes and other functions, the Bank also serves as a lender of last resort, responsible for making sure the financial system functions smoothly. This theme was chosen for the $1,000 note, a denomination commonly used at the time to settle accounts between banks. An earlier model for the $1,000 that CBN developed but discarded featured a lumber allegory, which was more closely aligned with the themes on the other notes.

Despite being produced by two printing firms, the overall look of the 1935 series is uniform. Note, though, that each company used a different font for the Bank of Canada inscription.

Source: British American Bank Note Company, 5 dollars, proof, 1934 | NCC 1976.212.57

Source: Canadian Bank Note Company, 100 dollars, proof, 1934 | NCC 2011.67.352

The Canadian Bank Note Company prepared two designs for the back of the $1,000 note. One featured an allegory of the lumber industry. But it was rejected in favour of an allegorical scene called “Security.”

Source: Canadian Bank Note Company, 1,000 dollars, proof, 1934 | NCC 1990.43.216

Source: Canadian Bank Note Company, 1,000 dollars, proof, 1934 | NCC 1990.43.213

Bank notes: A part of our visual culture

Images of industry appear elsewhere in the art and visual culture of 1930s Canada, including in public murals, sculptures and monuments. In fact, the façade of the Bank of Canada’s headquarters includes bronze sculptures featuring allegorical representations of Canadian industries, just like on the 1935 bank note series. Together, these images tell a story of Canadian cultural identity at a difficult time in the country’s history.

The Museum Blog

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.