Taking money back to basics

What is money—when you really stop to think about it? To understand how money works, and what it ultimately represents, we need to strip it down to its very basic function.

Carrots in your wallet

Let’s imagine it is the dim past and you are a farmer in with an abundance of carrots and a hankering for an omelette. With a bunch of carrots tucked under your arm, you stroll over to the chicken farmer next door looking for eggs. Sadly, he is in no need of carrots. So, you visit the blacksmith—he likes carrots. And though you don’t want the nails he has to offer, perhaps the chicken farmer does. So, you make a trade. But it’s not your lucky day: the farmer has no interest in the nails either. But he tells you he could use a loaf of bread and that the baker’s shed fell down and needs to be rebuilt …and so on.

Now, if you had a token that all the villagers could agree equalled the value of a bunch of carrots, a handful of nails, a dozen eggs or a loaf of bread, you’d be eating your breakfast in ten minutes instead of trudging around the village most of the morning. That token is called money.

To be successful money, however, that token would also need to be special and unusual—in case some scoundrel decided to copy it. Counterfeiting is as old as money and so are the ways of to avoid it.

It starts with gold

The earliest coins we know of were issued around 2,500 years ago by King Alyattes of Lydia (in modern Turkey). They were made of electrum, a naturally occurring combination of silver and gold. Some sharp Lydian bureaucrat must have reasoned that, to avoid counterfeiting, money needed to be made of a rare material. Gold and silver were ideal because they were difficult (but not too difficult) to mine and were already considered valuable. Basically, mining gold and turning it into a coin was not worth the cost and effort to a counterfeiter. So began the millennia-long practice of creating money with intrinsic value. That’s money made of a valuable material—coins literally worth their weight in gold (or silver or bronze or copper).

Everything the mythical King Midas touched turned to gold. This proved somewhat impractical, so the gods told him to bathe in the River Pactolus to rid himself of the gift. That river had deposits of the gold alloy used in the first coins, these pieces from the Kingdom of Lydia.

Source: 1½ stater, Ancient Greece, Lydia, 650–561 BCE | NCC 1967.83.286

Cross-border shopping

This “holey dollar” from Prince Edward Island was originally a Spanish piece of 8. The doughnut part was valued at 5 shillings, and the piece punched out (the “dump”) was worth 1 shilling.

Source: 5 shillings, Prince Edward Island, Canada, 1813 | NCC 1969.225.2 | 1 shilling, Prince Edward Island, Canada, 1813 | NCC 1972.8.1

Despite the lack of trains, trucks or internet connections, long-distance trade was a feature of the ancient world for a very long time. For untold centuries before European contact, Indigenous North Americans had trading networks that ran from Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico. Trade routes from Southeast Asia reached southern Europe in 100 BCE. And archeological evidence shows that Britain continued to trade with the Mediterranean region during the Dark Ages, centuries after the Romans left.

Money would have simplified these international transactions a whole lot. But, just like today, a standard world currency wasn’t available. Or was it? Because most coins were made of known materials, like gold and silver, you only needed to weigh one to know what it could buy. So, as time went on, Venetian ducats, Spanish doubloons or English nobles turned up in pockets all over Europe, Asia, Africa and even here in Canada.

A bright idea from the Middle Ages

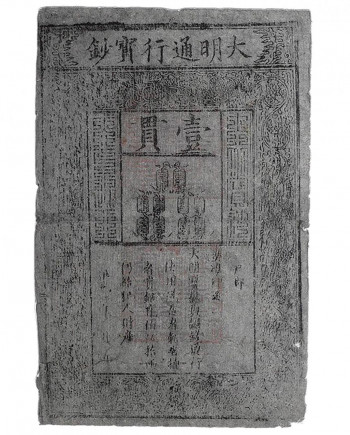

Back in the 14th century, somebody at the head office of China’s Ming Dynasty got a brilliant idea. Instead of lugging around sacks of copper coins when you wanted to make a big purchase, why not park the coins in a vault someplace and use an official piece of paper to represent them? The coins would stay put, and the paper note would circulate from buyer to seller and so on—all without the aid of a mule or a visit to the chiropractor. It was the first paper money. It was also the first step in history’s slow reduction of money’s physical characteristics—from a piece of gold to a mere line in a ledger.

Until the 20th century, all paper money functioned much like the Ming notes did. Every paper dollar was supposed to represent a dollar’s worth of precious metal locked in a vault someplace. When national governments issued money based on the amount of gold they had in their vaults, they were said to be on the gold standard.

Of course, convenience came at a price. First, the value of precious metals forever fluctuates, so paper money was frequently revalued. Second, those issuing money couldn’t all be trusted to have enough gold to back it. In some cases, they had no gold at all!

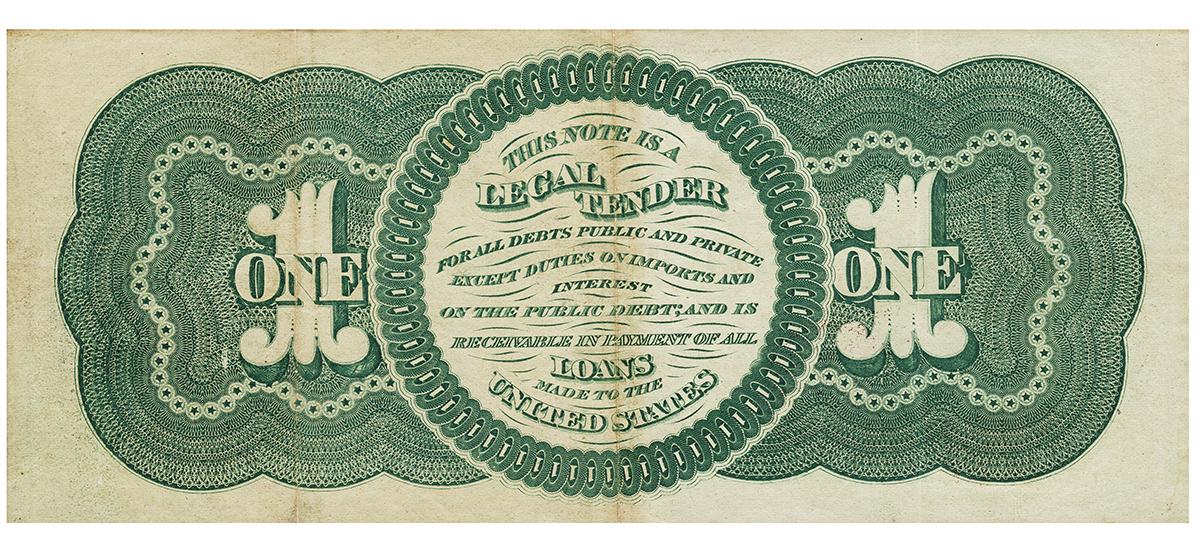

But the gold standard’s biggest downside was its inflexibility. There’s only so much gold and silver in the world and economies were unable to grow without inputs of precious metals. So, during times of great turmoil, such as war, governments tended to conveniently dispense with the gold standard. They issued paper money without any more backing than a simple guarantee of its value and maybe the chance to trade it for gold when things calmed down. This money was called legal tender. It worked. People accepted it, and it circulated just like any money. It was the second stage in the stripping away of money’s physical form.

Enter fiat money

No, it has nothing to do with a little Italian car. It has everything to do with public trust—and a bit of faith. Basically, fiat money is a social contract: a government tells the public that the money it issues has value. Most governments are unlikely to go broke, so people are comfortable with that. We’ve been using fiat money in Canada since the Wall Street Crash of 1929. And it has remained stable, reliable and fully trusted ever since. It just doesn’t buy as much as it used to.

It’s just numbers now

It’s helpful to understand that modern currency is just one of several delivery systems for money, along with debit cards, cheques and e-transfers. Money itself is often simply the numbers on your bank statement. This is the ultimate removal of money’s physical form, its reduction to a few digits on a spreadsheet. Money has been like that for a couple of generations now. And reducing money from gold in the hand to a row of numbers on a statement reveals to us the very basic function of money.

“Time is money”

When Benjamin Franklin (allegedly) coined this phrase, he was thinking of the cost of laziness: how sitting on your duff playing the 18th century equivalent of a video game costs you not only the price of the game but also the income you could be making instead of playing it. This was a form of what economists call an opportunity cost—giving up something to take advantage of another opportunity. (Check out our blog on this topic.)

But to flip it around: “money is time.” When you get right down to it, what money really represents is somebody’s time and effort to do something, be it building a shed or manufacturing a computer. The basic material costs nothing—in terms of money. After all, nobody writes a cheque to Mother Nature for her timber and iron ore. You’re paying for somebody’s time and effort to extract resources and for other folks to refine them so that manufacturers can make them into things. What it costs the environment is a different story. Because, in the end, our entire economy is rooted in Earth’s resources and our exploitation of them.

Just because our money’s mostly digital doesn’t necessarily mean we’re using fewer resources than in the past. Finalizing Bitcoin transactions produces a carbon footprint much bigger than the one created by mining a similar value of gold.

Source: Bitcoin mining computer, Ant Miner, China, 2013 | NCC 2018.12.1

So, if you were the historic farmer selling carrots for a token such as a coin, you were storing your time and effort in a medium that is very robust. This is one of the key features of money: its capacity to store value in a form that is durable. Long after the carrots have rotted, the coins will remain functional, storing your skills and efforts in a trusted format that you can exchange for the products and services of others. It still works that way today, no matter whether it’s a number on your bank statement or a bill in your wallet.

The Museum Blog

Love tokens: Change of heart

For centuries, people have been adding alternative messages to coins as political protests, advertising, commemoration and—most charmingly—love and affection. Such things are called love tokens.

Three 50-cent pieces: The big changes to our small change

The maple leaves, beavers, schooners and caribous appear unchanged every year on our regular issued coins. But the 50-cent piece is a different story, because every time our coat of arms has changed, so has the coin.

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.