After 60 years in private collections, the most prestigious of Canadian coins, the “Emperor,” has come back to Canada. The 1911 silver dollar has a history to match its prestige, and it now has a permanent home in the National Currency Collection of the Bank of Canada Museum.

A brief history of Canadian coins

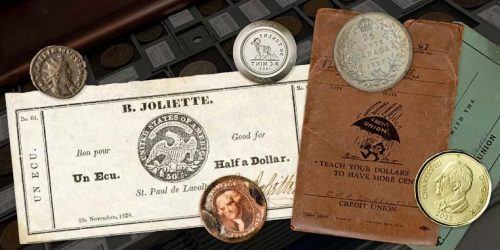

Until 1858, coinage in Canada was a mixed bag of foreign and provincial government coins as well as bank and private merchant tokens. After the fall of New France in 1759, provincial governments used the British pound as their currency. The problem was that British coins were in short supply. So, merchants and banks resorted to accepting gold and silver coins from Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Germany and the United States. In 1858, the Province of Canada reined in the currency chaos and issued an official provincial coinage, the first of the British North American colonies to do so. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland followed suit and issued coins in 1861, 1864 and 1865, respectively. Grumblings about a need for coinage were also being heard in British Columbia.

The want of a dollar: from the Gold Rush…

The gold rushes that struck the West Coast from Eureka, California in 1848 to the Klondike in 1897 gave many Westerners ready access to precious metals to pay for things. “Forty-niners” (the droves of people who came to California in 1849 seeking their fortune in gold) and their Canadian brethren preferred coins to paper money. It was a matter of trust and confidence. This preference was so widespread that the Government of British Columbia planned to release gold coins for circulation in the province. Unfortunately, Canada’s earliest gold coins never saw the light of day. There was too much internal strife at the New Westminster government: no one could agree on where to locate the mint.

The coveted gold BC pattern coins were prepared in two denominations, 10 and 20 dollars. They followed the technical specs of their American counterparts, the Eagle and Double-Eagle.

Source: 10 dollars, pattern, British Columbia, Canada 1862 NCC 2016.50.1 | 20 dollars, pattern, British Columbia, Canada, 1862 NCC 2016.50.2

So, British Columbians continued using British and American gold and silver coins. But when British Columbia joined Canadian Confederation on July 20, 1871, its citizens were required to adopt Dominion coins and notes. However, Canadian coins were in denominations below 50 cents. With the high cost of goods in the West, the low-value coins were not sufficient, and the British and American gold coins were too scarce to meet demand. American silver dollars had been quite popular in British Columbia, so residents wanted a Canadian silver dollar.

… to the House of Commons

In 1910 the first sign of a Canadian silver dollar appeared in Canadian legislation. For years, Members of Parliament (MPs) from British Columbia had petitioned the Dominion government to include the production of a silver dollar in the Currency Act. Those demands were largely ignored; in Eastern Canada, bills were generally preferred to large coins. But when Canada opened its own mint in 1908, it was then able to appease the people of the West.

Finance Minister William S. Fielding was the main overseer of Canadian currency legislation. He also had jurisdiction over the Ottawa branch of the Royal Canadian Mint and was not in favour of a silver dollar. The government made an amendment to the Currency Act (Bill 195) requiring Canadian gold coins to match the size of American gold coinage rather than that of the British sovereign. During the debates over that bill, Mr. Fielding first mentioned the inclusion of a large-format silver coin valued at one dollar for circulation in Canada.

And so, Bill 195 included a requirement for a Canadian silver dollar.

I propose to insert the provision to authorize us to make a silver dollar. Hitherto, I have not viewed it with much favour and have not thought it necessary, but representations have been made to me, chiefly by honerable gentlemen from British Columbia on both sides of the House, that a silver dollar is desirable.”

The Honourable William S. Fielding, Minister of Finance

Axing the coin

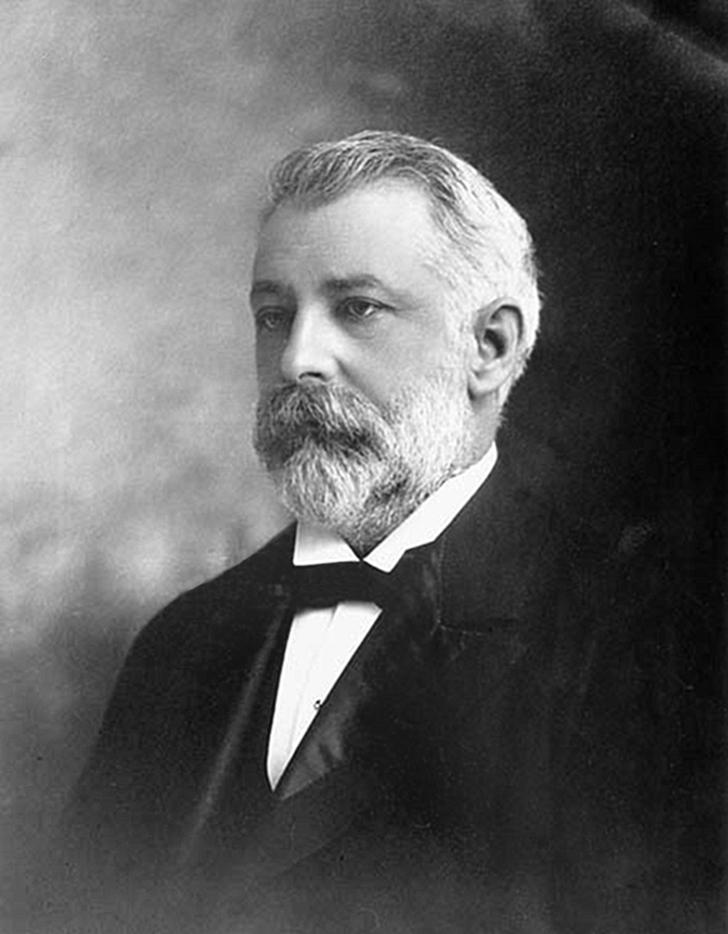

On May 4, 1910, Bill 195 was passed into law. The government gave the green light to order the production tools and equipment required to strike silver dollars. The Ottawa branch of the Royal Mint did not have a coin press for large coins, and the main branch in London, England still produced the dies (the metal forms that strike the patterns on coins). So on November 10, 1910, Dr. James Bonar, Deputy Master of the Royal Mint in Ottawa, ordered master dies for the new dollar. However, die production in London fell way behind schedule, and delivery was delayed for almost a year. Little did anyone know that a change in Canadian government would seal the fate of the coin before it was even made.

In any new government, policies get reversed and new programs are cancelled. And with the election of Sir Robert Borden’s unionist government on October 10, 1911, one of the first orders of business was to scrap production of the silver dollar. An official reason why the Borden government cancelled production has yet to be discovered. But in a letter to Evelyn Cecil, MP, Deputy Master Bonar appears to associate it with the removal of the reference to God (Dei Gratia) from Canada’s coins. This was causing quite a stir among Canadians at the time.

The dollar has not been approved by the new Government (tho’ it was not Graceless).”

James Bonar to Evelyn Cecil, MP, dated December 11, 1911

The few pieces that have survived

Unlike other historic coins that were produced in the thousands only to be relegated to the melting bin, the 1911 dollar was not made at all. The Ottawa branch of the Mint shelved the master dies and would not use them until the production of the 1936 silver dollar. It was later discovered that the Mint in London had made three trial strikes, or test samples. Two were in silver and one in lead. They have since been catalogued as pattern coins, which are unique and not intended for circulation.

The story of these three legendary coins is every bit as intriguing as the story behind the production of the coin itself. The Royal Mint Museum in the United Kingdom owns one silver pattern of the 1911 dollar which it has loaned to the Bank of Canada since 1976. The coin has been prominently displayed in the Bank of Canada Museum (formerly the Currency Museum) since 1980.

The discovery of the lead pattern coin was completely accidental. Likely the lead pattern was in the shipment of the master dies that came to Canada in 1911. For some reason, the dies wound up in the offices of the Department of Finance. When its offices were moved from Parliament Hill in 1977, the lead pattern was discovered in a drawer. The coin moved to the National Currency Collection of the Bank of Canada that same year.

The elusive second silver pattern has changed hands over the decades since its first public appearance in 1960. No one is sure how the piece got out of the Royal Mint in London. Some speculate that an official at the Mint sold it to King Farouk of Egypt in the 1920s. When the king was deposed in 1952, his entire coin collection was sold, including the silver dollar. However, a more plausible story is that it had belonged to the family of Deputy Mint Master William Frey Ellison-McCartney. In 1960, the McCartney family sold the coin to a British coin dealer, Blair A. Seaby. Seaby displayed it for the first time ever at the annual convention of the Canadian Numismatic Association held in Sherbrooke in 1960. A week later, Seaby displayed the coin at the American Numismatic Association convention in Boston. It did not sell at either convention, and he returned to England, coin in hand.

It is believed the coin’s moniker,“Emperor of Canadian Coins,” dates back to 1976 in Toronto, when Frank Rose auctioned the 1911 dollar as part of the famous John L. McKay-Clements collection. It was the first offering of the coin since its public appearance in 1960. Following the McKay-Clements sale, the silver pattern coin changed hands on several occasions. A prominent collector from Calgary, George H. Cook, bought it in 2003 at the public sale of the Sid and Alicia Belzberg collection.

Mr. Cook held onto the coin for nearly two decades until he passed away in 2018, and his collection was auctioned in the United States. A prominent Canadian numismatic dealer acquired the coin and offered it to the Bank of Canada Museum to ensure that Canada’s most important coin remains within Canada’s public cultural sphere. Quite a journey for such a small object.

Finally in public hands, the 1911 silver dollar pattern is now part of the National Currency Collection where it joins its silver and lead counterparts. For the first time since their minting, all three coins are together and will be on display in the Museum’s permanent galleries.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Bank of Canada Museum’s acquisitions in 2024 highlight the relationships that shape the National Currency Collection.

Money’s metaphors

Buck, broke, greenback, loonie, toonie, dough, flush, gravy train, born with a silver spoon in your mouth… No matter how common the expression for money, many of us haven’t the faintest idea where these terms come from.

Treaties, money and art

The Bank of Canada Museum’s collection has a new addition: an artwork called Free Ride by Frank Shebageget. But why would a museum about the economy buy art?

![Because they are missing the reference to God [Dei Gra], the 1911 coins have come to be known as “graceless”. This controversy may have led to the cancelling of the silver dollar. Coins, 2, identical designs but one has fewer letters around the edge.](https://www.bankofcanadamuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/205-04_slver_dllr_Dei_Gra-740x398.jpg)