FAQs for students and teachers

Ever wondered who decides what images and portraits appear on our coins or bank notes? Or why we’ve chosen certain names and colours for our coins and notes? This guide helps answer some of your money-related questions.

What is money?

Money is a tool we use to make trading easier. It provides people with an object that has an agreed-upon value. Money can take almost any form, as long as we all agree it is worth a certain amount and has these five characteristics:

- It must be easy to transport (so you can bring it to the store).

- It must be rare but not too rare (so you can have enough of it to make trading easy, but not so much that it loses value).

- It must be divisible it into smaller pieces (so you can get change back if you buy a $2 candy with a $20 bill).

- It must be hard to fake (no one wants fake money).

- It must be durable (so it won’t be easily destroyed in rain, snow, heat or cold).

Who makes Canada’s money?

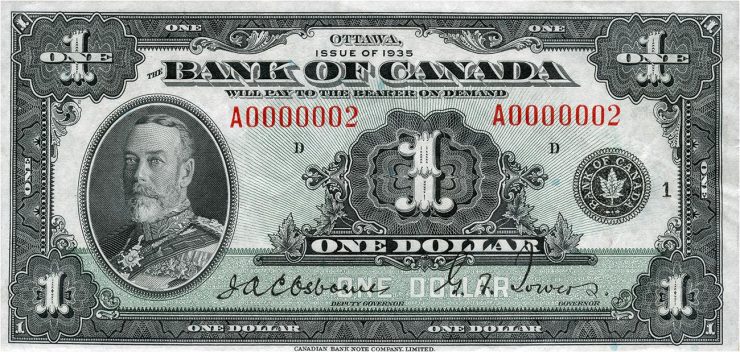

The Royal Canadian Mint makes all of Canada’s coins. The Bank of Canada designs and produces bank notes (or bills), which are printed by the Canadian Bank Note Company.

Who decides what goes on Canadian money?

For bank notes, the Bank’s Currency Department works hard to find images that best represent Canada and Canadians. The development of the current $10 note in 2018 was the first time Canadians were consulted directly about who should appear on a bank note. This has continued with the new $5 note. However, the Minister of Finance makes the final choice.

Circulation coins in Canada are produced slightly differently. Their images are created by the Royal Canadian Mint, which designs each coin around a Canadian theme. The Mint works with Canadian historians, the public and artists to find themes and images that represent important Canadian milestones. Then they send the designs to the federal government for approval.

Can anyone be on the money?

There are four rules about whose image we can put on our bank notes:

- They need to be real people. We want to show people from our history on the bank notes. So, while you won’t see Anne of Green Gables on a future note, you could see her creator, Lucy Maud Montgomery.

- They need to be Canadian. But they don’t need to have been born here.

- They need to have done something important for their community. This gives Canadians something to be proud of.

- They need to have been deceased for over 25 years. We want to display people who have had a long-term impact on Canada, not just who are popular right now. The one exception is the reigning monarch (king or queen), who always has a place on the front of the $20 note.

The rules around portraits on circulation coins are different. All coins have the reigning monarch on the “heads” side. But the Mint can be more creative on the “tails” side. Coin designs must be in both English and French and meet one of the following rules:

- They need to reflect Canada's heritage, values and culture.

- They need to commemorate, celebrate or promote Canada by showing themes that matter to Canadians.

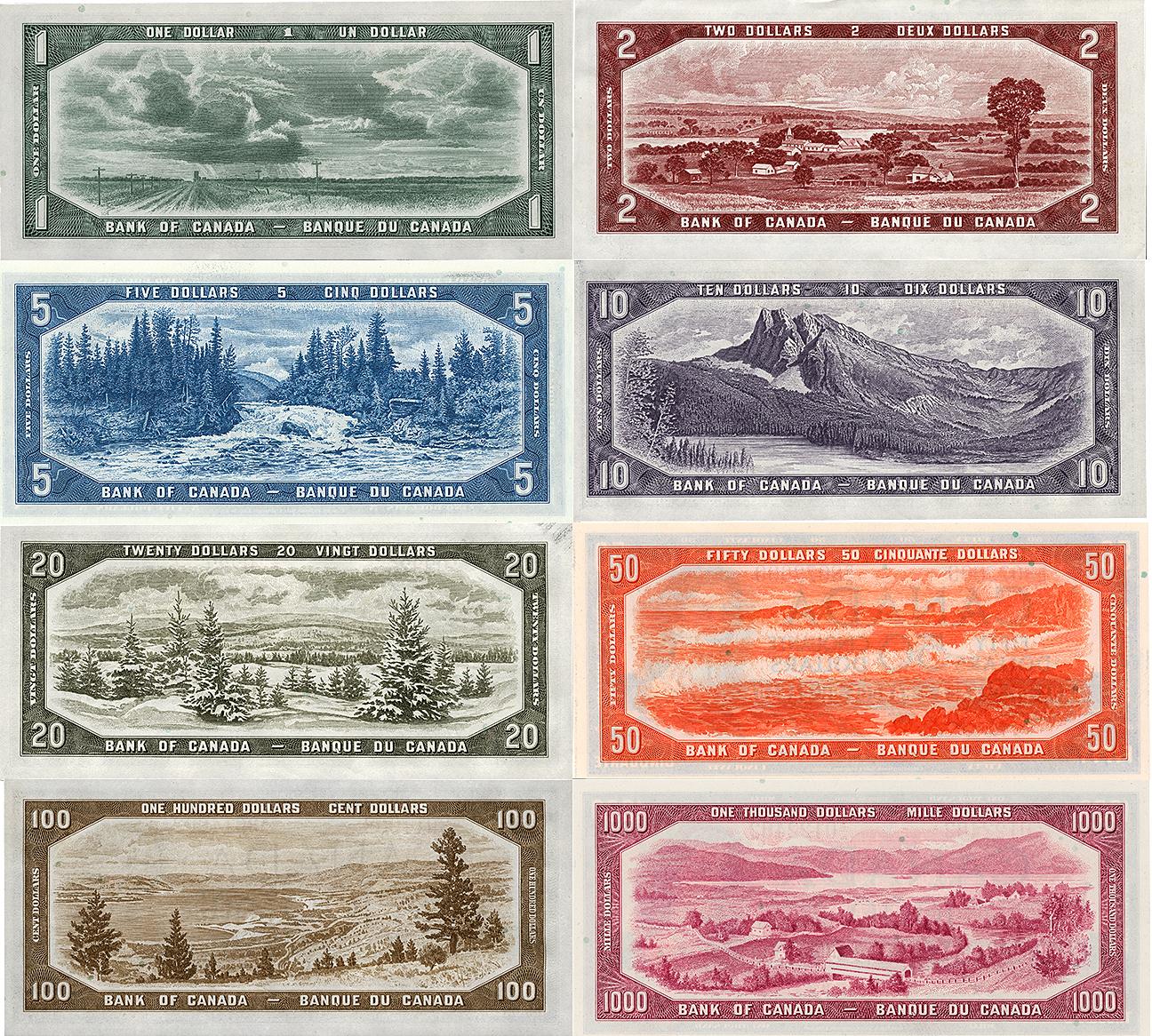

Why are Canadian bank notes different colours?

Canadian notes were first printed in different colours to make each [note/one] easy to recognize and to prevent counterfeits. Over a hundred years ago, criminals would try to “raise” bank notes. This meant adding a zero to a note like the $5 to make it a counterfeit $50. It’s much harder to do this when every note is a different colour.

Today, with all our other security features, counterfeiting isn’t as much of a concern. But our bank notes still come in a variety of colours to help people tell them apart.

Why are our coins different sizes?

Differently sized circulation coins help us recognize them by touch. When you reach into your pocket, you can tell if you are holding a loonie or a dime. All of our coins increase in size as they increase in worth, except for the dime.

Our coins are the same size as US coins. This custom goes back to colonial times, when trading between the two countries was mostly done with cash.

Why are our bank notes made of plastic?

Actually, our notes are made from a plastic-like polymer. Before 2011, they were made with a cotton-based paper. Polymer notes last up to four times longer than paper, so they have less impact on the environment. They are also recyclable and can have more security features than paper notes.

How do we prevent counterfeiting?

A number of security features in our bank notes keep people from counterfeiting them. Here are a few you can check to make sure your bank notes aren’t counterfeit:

- Material: The polymer material of the notes has a unique feel to it. Compare the feel of a polymer note and an older paper bank note.

- Ink: You should feel raised ink bumps on the numbers and on details of the images, such as the shoulders of the portrait.

- Window: Newer notes have a clear window, which is an unprinted area of the polymer.

- Hologram: Your bank note should have a holographic picture on it, of either someone’s face or part of the Parliament buildings. Tilt and twist the note to reveal the colours of the hologram.

- Detail: The process for making notes has many precise steps. Look closely at the details in your note, such as the eyes in the portrait.

Counterfeiting is uncommon for circulation coins. First, coins aren’t worth much, so making a counterfeit coin would cost more than the fake coin would be worth. Second, coins have many fine details that are hard to copy, such as the Queen’s portrait and the lettering.

Newer $1 and $2 coins have extra security features, including:

- A virtual image: A maple leaf appears as you tilt the coin.

- A maple leaf security mark: One or two circles with maple leaves inside them appear on the side of each coin.

- Edge lettering: The edge of each coin says Canada and gives the value of the coin.

Why are some bank notes horizontal and others vertical?

Canada’s bank notes are all changing to a vertical format. This started with the release of the $10 Viola Desmond note in 2018. The vertical format provides more space to display the portrait. Other countries that also have vertical banknotes include Switzerland, Israel and Venezuela.

Is a nickel still made of nickel? What about the other coins?

Even though the nickel coin no longer has much nickel in it, its name has stuck. All our circulation coins today are made from multi-ply plated steel—many thin layers of steel attached to small amounts of other metals to give them their colours and make them more durable. Many years ago, our coins were made from metals like copper, nickel and silver, but those metals are softer and more expensive than steel.

You can learn more about how coins are made from The Royal Canadian Mint.

What happened to the penny?

Canada stopped using the penny in 2013. A penny is worth so little that it was costing more than a cent to make each one! Also, many people didn’t like to carry pennies as they were heavy and took up space. Today, when buying with cash, we round to the nearest five cents.

Can we still use older coins and bank notes to pay for things?

You can still pay for things with all Canadian circulation coins newer than 1952 (except the penny) and most older bank notes. Some very old notes, such as the $1, $2, $500 or $1,000 denominations, can’t be used anymore. However, you can still bring them into a bank and have them exchanged for current notes.

Be careful when spending and accepting old bills. They don’t have all the security features of modern bills. But sometimes, if you’re lucky, they might be old enough to be worth more than their face value to a collector.

In 2021, the Bank will remove legal tender status from many old notes. But most notes, no matter their age, will stay functional until they disintegrate. See our blog on this subject.

Source: Various notes, Canada, 1935, 1937, 1954, 1986

Are special coins more valuable?

The Royal Canadian Mint issues commemorative coins to celebrate significant persons, special events and anniversaries. These are different than coins that are in circulation.

In general, circulation coins are not worth more than their face value, but some coins are highly sought after by collectors and can go on to sell for much higher prices.

How long have we been using money?

The idea of money predates coins and bank notes. Both China and Greece developed their own coins around 2,600 years ago. The Chinese developed the first paper money around the seventh century so that they wouldn’t need to carry so many coins. The notes and coins we use today are very different from the early Chinese examples: their coins were shaped like miniature farming tools and cast in bronze. The process of striking coins in precious metals began in ancient Greece and is still used today. The only difference, of course, is that our coins are no longer made of gold and silver!

Many objects have been used as money, including seashells, tea, salt and even teeth. For centuries, archaeologists have uncovered unusual items that were used specifically for trading.

Will we ever switch to a digital currency?

The Bank won’t be switching to using digital money any time soon, but we are looking into options for creating a central bank digital currency. So in the future, you might be able to buy things with an official digital Canadian dollar. Every year, payments using cash go down and payments using debit and credit cards go up. However, if someone doesn’t have a credit card, phone-based payment app or other technology, they still need to have access to their money. Ensuring money is available to everyone means the Bank and the Mint won’t stop producing bank notes and coins anytime soon.

Can the Bank print more money if it wants to?

The Bank prints new bank notes every year to make sure we don’t run out of them. But we have to be very careful about how much money we issue. If we print too much, it loses its purchasing power. This is called inflation and results in higher prices. The Bank issues enough money to keep inflation low, so that prices don’t go up too quickly.

The Museum Blog

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.

Speculating on the piggy bank

Ever since the first currencies allowed us to store value, we’ve needed a special place to store those shekels, drachmae and pennies. And the piggy bank—whether in pig form or not—has nearly always been there.