Joseph Idlout and the 1975 two-dollar bill

In the early 1970s, real people appeared in the vignettes on Canadian bank notes for the first time—including Joseph Idlout and his relatives.

The hunter and the filmmaker

He knew how to hunt well because he did it carefully. That’s why he was a great hunter."

- Peter Paniloo, Joseph Idlout’s son1

The hunter was Joseph Idlout. In the early 1950s, he was the leader of a small community of families, a summer hunting camp called Aulatsiivik on northern Baffin Island. At 38, Idlout was a man who had been brought up in the ancient hunting traditions of the High Arctic—a master of his craft. Everyone at the camp was part of the same traditions—except for one: documentary filmmaker, Doug Wilkinson.

Although Wilkinson was an outsider, he was nevertheless welcomed into the community. He lived among them as he filmed what would become a documentary for the National Film Board, Land of the Long Day. Wilkinson didn’t want his film to be a re-creation of pre-contact Inuit life. Instead, he sought to document Idlout and his community as they functioned at the time: a mixture of Western technologies and traditional practices. As he followed the families and their hunting activities through the brief Arctic summers, he and Idlout formed a strong friendship.

Wilkinson shot a lot of film, with both still and movie cameras. And from that treasure trove, some 23 years later, a single photograph was chosen to be made into a bank note engraving.

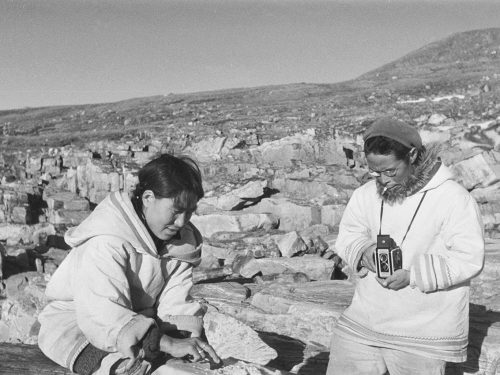

Wilkinson sought, as best he could, to understand the Inuit’s then-current culture, language and practices. And it went both ways. Idlout expressed a fascination with Wilkinson’s film and photography practice. He took lessons from Wilkinson, who gave Idlout a Kodak camera, supplies and a developing kit. Idlout’s photographs provide a unique perspective of the north Baffin Island region and can be found today, together with Wilkinson’s, in the Nunavut Archives.

He was Inuk, Angutialuk, a human being, a big man. Into his hunting he poured all the energy and emotion that a painter sets on his canvas, a writer from his pen."

- Douglas Wilkinson2

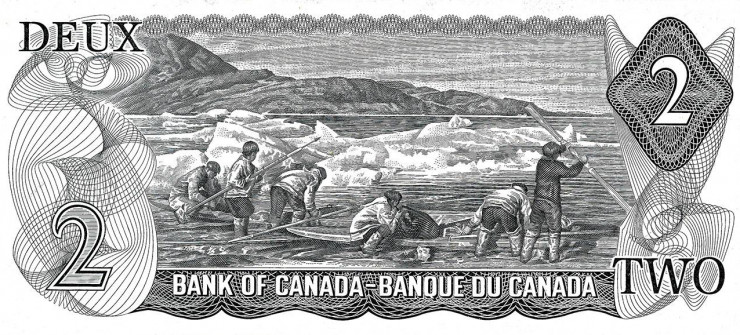

Deconstructing the engraving

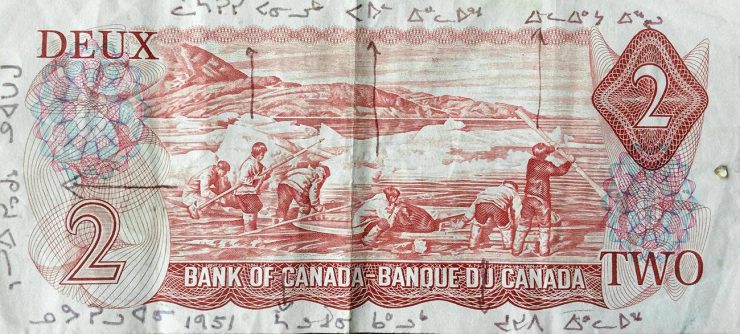

The Scenes of Canada series (1969–79) was loosely themed around landscape with human activity. The location for the $2 note vignette was Nuvuruluk, (a common place name meaning “insignificant point of land”) near Aulatsiivik. Engraver C. Gordon Yorke slightly altered this image to suit the note’s format, bringing the horizon down to fit the height of the bill. Clouds were added that echoed the ripples in the water, giving directional energy to the image. The hunters’ appearance in the engraving is identical to the photograph, and their families were easily able to identify them on the $2 bill.

The men of the hunting scene

This scene also appears in Wilkinson’s film, part of a hurried preparation to pursue a pod of narwhals sighted by Idlout amongst the ice floes. The men were readying harpoons and kayaks and inflating avataqs, sealskin floats that they would use to slow the whale’s escape. Apart from canvas for the kayaks and a few small tools, the hunters used the traditional gear of this ancient hunting practice.

A foot in each world

The early 1950s were what Wilkinson called “a difficult and critical time”2 for all Inuit people, a time of massive societal transition. At that point, Idlout’s community had long since become accustomed to tea, flour, biscuits, guns, gasoline, boats and other 20th-century commodities—paid for with the furs Idlout supplied to the Hudson’s Bay Company. When arctic foxes became scarce in the mid-1950s, he, like others in the community, began to rely on store credit, reluctantly adopting another feature of modern life: debt.

Hoping for better hunting, Idlout and his family moved 650 kilometers north to Resolute Bay, the site of a Royal Canadian Airforce base. Encouraging him to move, authorities assured Idlout that Resolute was a “land of plenty.” It wasn’t. And, like other families relocated to the frontiers of the Cold War by the Canadian government, the Idlouts became wards of the state.

When the new $2 bill came out in 1975, the way of life depicted on it was already a thing of the past. By the late 1950s, hunting, as the Inuit knew it, had become an unaffordable luxury—even to Idlout. For a time, he worked as an instructor in Resolute. He taught Arctic survival techniques to soldiers and helped acclimatize Inuit families relocated by the Canadian government from distant Northern Quebec. But it was a poor substitute for the life of a master hunter and respected community leader.

The sad story is that we were basically human flagpoles, so the Canadian government could assert sovereignty over the high Arctic."

- Lucie Idlout, Joseph’s granddaughter3

He knew the different ways that made the Inuit happy and the different ways that made white people happy. He could have two lives."

- Peter Paniloo1

In the end

It will continue being cold. It will always be the way it is. Someone will always need to know the land. We’re more than just hunters."

- Peter Paniloo1

Not knowing where he belonged, and unable to practice his vocation, depression and alcohol began to dominate Joseph Idlout’s life. He became a regular at the bar on the airbase. At 1:00 a.m. on June 2, 1968, he and his wife left the bar to head back to their village. His snowmobile broke down, so he sent his wife home with friends. He was able to fix the problem, but by 4:00 a.m., he hadn’t arrived home. His daughter called the RCMP. Idlout and his snowmobile were found at the bottom of a ravine later that day. His death was officially recorded as an accident. But Peter Paniloo knew his father better than that. Examining Idlout’s snowmobile tracks, Paniloo recognized that the “accident” was a suicide.

Resources and further study

Special thanks to Edward Atkinson and Sharon Angnakak of the Nunavut Archives for historic photographs and writer Kenn Harper for assisting with the image of the marked $2 bill. Thanks as well to Lucie Idlout, Joseph’s granddaughter, for fact checking, spelling and identifying family members.

Land of the Long Day. Directed by Douglas Wilkinson. National Film Board of Canada, 1952.

- 1. Between Two Worlds. Directed by Barry Greenwald. National Film Board of Canada, 1990.[←]

- 2. Wilkinson, Douglas. Land of the Long Day. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1969.[←]

- 3. Inuit scene on $2 bill has a dark, storied history | CBC Radio[←]

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2025 edition

From rare toonies to Métis scrip art, the Bank of Canada Museum’s 2025 acquisitions show how money and the economy shape Canadian lives.

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

The idea of the penny as the basic denomination of an entire currency system has been with Canadians for as long as there has been a Canada. But the one-cent piece itself has been gone since 2012.

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

In an ideal gold standard monetary system, every piece of paper currency represents an amount of gold held by an authority. But in practice, the gold standard system’s rules were extremely and repeatedly bent in the face of economic realities.