Students will learn about inflation: what it is, what it means and how it’s measured. They will also learn about how the consumer price index is calculated and create their own student price index to measure the prices that matter in their everyday lives.

Overview

Big idea

Inflation is a measure of how much prices change over time, and the consumer price index (CPI) is the main way we measure it.

Total time

Approx. 60 minutes of instructional time, which could be delivered in one or two classes depending on class discussion.

Grade levels

Grades 10–12

Subject areas

- Economics

- Business

Learning objectives

Students will:

- define inflation

- explain the consumer price index and how it is calculated

- calculate their own price index

Materials

Classroom supplies and technology

- a computer with internet access and a screen or projector to show videos

- computers or tablets with internet access for students (one per group of four students).

- pencils and pens

- calculators

Graphic organizer

Download and print the following:

- Graphic Organizer - Student price Index — one copy for every four students

Online resources

From the Bank of Canada:

From Statistics Canada:

Activity 1: What is inflation?

Students will learn about inflation: what it is, how it has changed over time and why the Bank of Canada targets low and stable inflation.

Time

15 minutes; allow extra time if needed for students to access computers for the hands-on exercise.

1.1 Opening discussion

Ask your students a few questions to get them thinking about inflation:

- How much did you pay for candy when you were younger? What does it cost now?

- How much did your parents pay for candy when they were kids?

- How much did your grandparents pay?

- Why do prices change?

1.2 Video and recap

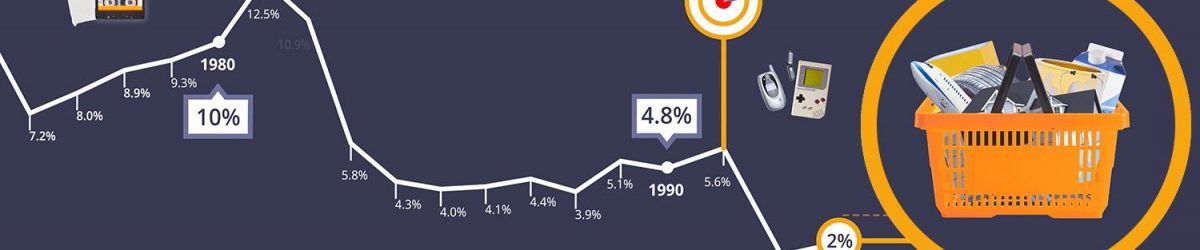

Play the Bank of Canada’s Inflation over time video.

This video is available with subtitles. A transcript can be downloaded directly from the YouTube page.

Provide a short explanation of inflation, recapping what was said in the video:

- Inflation means that the same thing costs more over time.

- When inflation is stable, this increase happens slowly and it’s hard to notice from year to year. It’s easier to notice when you look back 10, 20 or 50 years.

- A little bit of inflation is a good thing. It means that the economy is growing.

- High inflation means that people might not be able to afford the things they need to live because prices are rising faster than their incomes. Money loses its value because the same amount of money can’t buy as much as it could just a few months earlier. The economy works best when inflation is stable and predictable.

- As Canada’s central bank, the Bank of Canada has a responsibility to make sure that the Canadian economy is stable.

- The Bank of Canada’s monetary policy targets a 2 percent inflation rate. “Monetary policy” refers to the plan of action agreed by a country’s government and its central bank for how the central bank will manage the economy.

1.3 Hands-on exercise

Give your students a chance to play with the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator.

- Encourage them to think of the last thing they bought and enter that price into the inflation calculator.

- Students can use the year they were born to see how the price of that item has changed over their lifetime.

- They can also use other significant years to see what the item cost in those years (for example, during the First or Second World War).

- Suggest that they enter an average income to see the corresponding change in income and prices. The median household income in Canada in 2015 was $70,336 (see the 2016 Census topic: Income from Statistics Canada), but you can also use the median household income for your province (see the Income Highlight Tables from Statistics Canada).

- It’s true that a dozen eggs cost $0.31 in 1935, but average personal income was $313 per year. Things cost more over time, but generally people earn more over time as well.

Activity 2: Student price index

Students will learn that the “basket of goods and services” is the marker for the consumer price index (CPI) and create their own student price index.

Time

40 minutes

2.1 Video and recap

Watch the Overview of Canada’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) video from Statistics Canada to help explain what goes into the CPI and how it is calculated.

Use this opportunity to explain a bit more about the CPI. For example:

- The CPI is made up of more than 600 different goods and services, classified into 8 basic categories: health and personal care; transportation; clothing and footwear; household operations and furnishings; shelter; food; alcoholic beverages and tobacco products; and recreation, education and reading.

- Not everything we buy is in this basket. It would be impossible to include every single consumer item. Because a lot of goods increase in price at a similar rate (known as price behaviour), we can get an accurate measure of overall price changes in the economy by using these 600 or so representative items.

- Every month, Statistics Canada conducts retail pricing surveys right across the country. In total, more than 1,000,000 price quotations are collected, and new prices are recorded. By comparing the new prices of this fixed basket of goods with the old prices, we can calculate the rate of inflation.

2.2 Discussion

Ask students:

- Based on what we’ve learned, what’s the ideal inflation target?

- Answer: Between 1 and 3 percent, so we target the mid-point, 2 percent.

- How can we find out what the rate is this month? What would be a reliable and accurate source of information?

- Show the students the Statistics Canada Consumer price index portal. Currently, the consumer price index can be found on the rightside of this page, under “Key indicators.”

2.3 Hands-on exercise

Students will work together to make a student price index.

Individual work

Ask your students to make a list of the types of things they buy. Items should include food, clothing, transportation, health and personal care, and recreation. Their list should include at least one per category.

Group work

When students have completed their personal lists, organize them into groups of four. Distribute one graphic organizer per group.

- Each group will come up with its own student price index based on the purchases group members make on a regular basis.

- The students will discuss their own lists and agree on one item from each category to include in their student price index, things that are representative of what the average student would buy.

- The students will then research the current price of these items using online stores and flyers. By comparing three different sources of information, they will come up with an average price and put it in the group’s graphic organizer under “current price.”

- The students will enter their current prices in the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator to find the 2002 price for each item they have selected. They will then record this data on the graphic organizer. Students should use the following calculation to find the current index value:

\(Current\,index\,value\) \(=\,100 \times \left( \frac{Current\,total\,cost}{2002\,total\,cost}\right)\)

- Prices are measured against a base year. The base year is 2002, and the basket for that year is given the value of 100. In 2017 the CPI averaged 130.4, which means that what you could buy for $100 in 2002 cost $130.40 in 2017.

- Each group will check to see if their student price index per category matches the current month’s CPI on the Statistics Canada website.

- At the time of this writing, you can find this by clicking on “Consumer Price Index” in the “Key indicators” column on the right, then scrolling down to “Table 1: Consumer Price Index, major components and special aggregates, Canada – not seasonally adjusted.”

2.4 Discussion

Your index might be close to the current month’s CPI, or it might not be – calculating the CPI is complicated. Here are some reasons the two indexes might differ:

- The CPI varies by region. For example, the cost of fresh fish can be higher in Ontario than in Nova Scotia.

- It varies by season. Strawberries can cost far less in June than in January.

- Some elements also fluctuate more than others, like gasoline prices. If you’re living in a remote community, the cost of goods in your town may be vastly different from the Canadian average. These are challenges for economists who need to calculate an average in a large and varied country.

Statisticians and economists also have a challenge in measuring the changing quality of items through history. For example, a phone costs much more now than it did 20 years ago, but 20 years ago all a phone did was make a phone call. Now it is a computer, a GPS, a camera, even a flashlight. CPI baskets have to be constantly adjusted to keep pace with the invention of new goods and the improvement in quality of existing goods.

As a class, discuss:

- What student index value does each group have? Why are they similar or different?

- What kinds of prices have fallen, rather than risen, over time?

- For example, 50 years ago, a calculator or a pineapple were expensive luxuries few could afford. Now they are more commonplace and affordable to more people. A computer costs less now than it did 20 years ago and can do far more.

- How might your plans to buy something change if prices change? How could your change in plans affect the economy?

- For example, if you believe the price of a new smartphone is going to jump from $1000 today to $1200 next week, you’re more likely to buy one now, before the price goes up. This creates increased demand, and sellers are likely to increase prices even faster or further. Conversely, if you think the price of a phone is going to drop from $1000 today to $800 next week, you are likely to wait rather than buy. This supresses the demand for goods, and prices are likely to fall even further.

- This is an example of a price change for a single good. Inflation has a similar impact on consumer behaviour in that consumers find it difficult to plan for the future if prices change dramatically from year to year or decade to decade.

- This is easiest to see when you look at hyperinflation—when the prices of goods and services rise more than 50% in a month. This has happened in countries all over the world at different times in history. One of the most well-known examples occurred during the Weimar Republic in Germany after the First World War. The government printed more money to pay reparations after the war. The reparations also led to a shortage of goods. Since there was more money in circulation and fewer goods available for sale, inflation rose at a rate of 20.9 percent per day, which meant that prices doubled every 3.7 days. Imagine how hard it would be to plan day to day when prices are rising that fast.

Conclusion

Wrap up the lesson by recapping what was learned and by explaining the role of the Bank of Canada and inflation targeting.

Time

5 minutes

Key takeaways

- The Bank of Canada’s monetary policy focuses on protecting the value of Canadian money by keeping inflation low, stable and predictable. The Bank of Canada uses the CPI, as well as other economic indicators, to measure inflation and adjusts monetary policy to keep inflation between 1 percent and 3 percent. This is called inflation targeting. The Bank manages inflation by raising interest rates to cool the economy or lowering interest rates to heat it up (for more information about how this works, see the Bank of Canada’s backgrounder on the inflation-control target).

- Inflation targeting works best when people’s behaviour reinforces the inflation target. If people expect that prices will rise, on average, by about 2 percent each year, employers and workers are more likely to agree to a 2 percent wage increase to compensate for the higher cost of living. Wages affect the cost of producing goods and services, and the cost affects their prices. This cycle helps the Bank keep inflation on target.

- The CPI is also used to calculate changes in government payments such as the Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security. It also affects cost-of-living adjustment clauses in labour contracts, which link wage increases to the CPI. For example, if your grandmother gets a pension cheque, that payment will automatically get bigger over time, so she can keep up with rising prices for her groceries or rent. Or, if you get a job each summer, your pay should increase a little bit every year, to keep pace with inflation.

Extensions

- Expand the chart in the graphic organizer to track prices for other years. Students can then use the following calculation to find the percentage increase from year to year (X = the later year and Y = the earlier year).

- Research historical and contemporary examples of hyperinflation, such as Germany (Weimar Republic) from 1922 to 1923, Zimbabwe from 2007 to 2009, Venezuela in 2016.

- Advanced students can explore the Statistics Canada’s Consumer price index portal further, using the “Data” option on the Consumer Price Index page. By selecting an individual table on this page, the data becomes customizable, this data becomes customizable, and you can download it to use in your spreadsheet software.

\(Z\)

\(=\left[\frac{Year\,X\,Index\,Value} {Year\,Y\,Index\,Value} \times 100\right]\)

\(-\,100\)

We want to hear from you

Comment or suggestion? Fill out this form.

Questions? Send us an email.