Tee, thé, cha, tsài, tè, teo, chai, teh, chay—these are all words for the beverage made from leaves of the evergreen shrub Camelia sinensis. Wars have been fought to control its trade and gifts of it have been made to ensure peace. It has even been used as currency. In central and northern Asia, bricks of tea were a unit of value and medium of exchange well into the 20th century.

China had a monopoly on the tea trade right up until the 19th century and, as the taste for tea spread, it became an increasingly valuable commodity. It was exchanged for horses in Mongolia and Tibet. Russian caravans travelled for months across Siberia to trade furs for it.

Tea in the form of bricks was durable, easy to pack and, under the right conditions, could be preserved indefinitely. At factories in China’s Sichuan Province, freshly picked leaves were steamed, pounded into powder and then packed into moulds. The bricks were then dried or baked in the sun to harden.

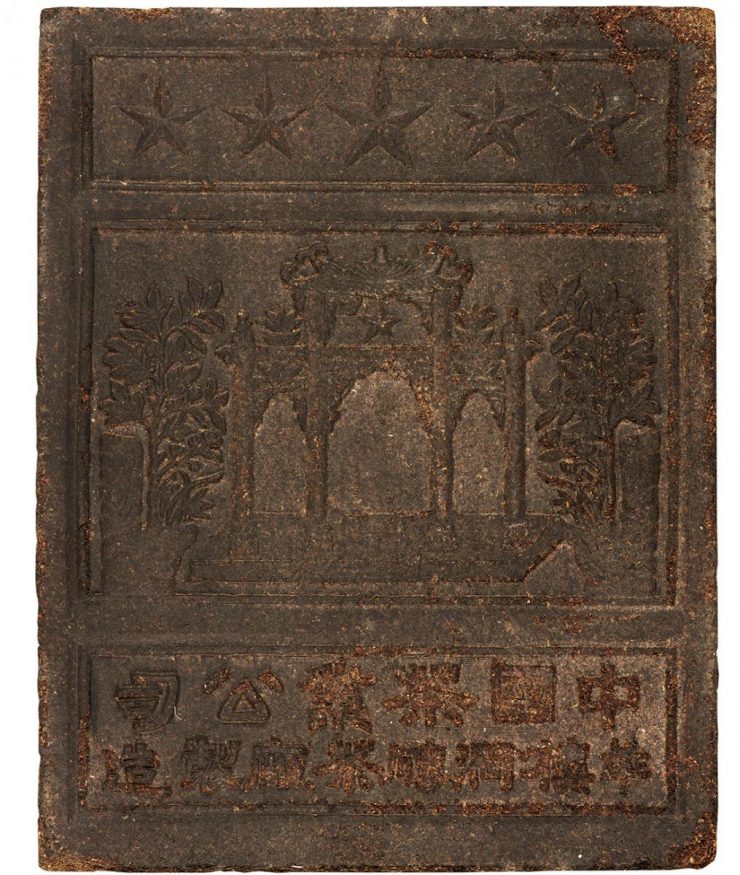

The characters tell us that the brick was made by the China Tea Industrial Corporation at the Zhao-Li-Qiao Tea Brick Factory in Hubei Province. Tea brick, China, mid 20th century

The value of a brick depended on both the quality of the tea and the distance it had travelled from China. A French missionary travelling in Tibet in the 19th century wrote, “men bargain by stipulating so many bricks or packets (4 bricks) of tea.” Workmen and servants were paid in bricks of tea and a horse cost 20 packets. At the beginning of the 20th century, Western adventurers in remote parts of Mongolia and Tibet found that they couldn’t use gold or silver to buy supplies, but could only use tea.

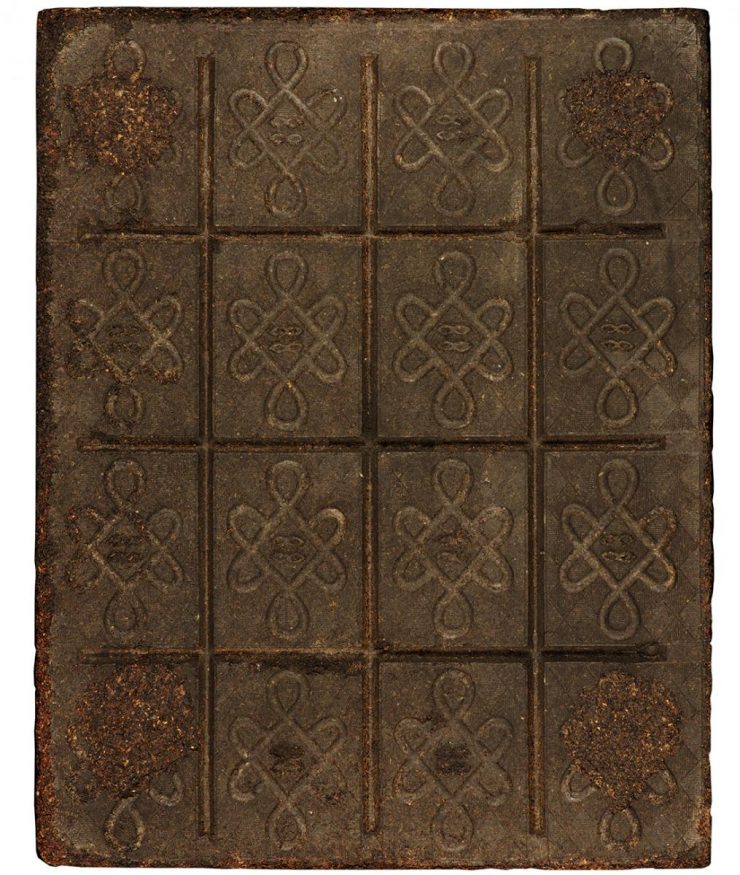

A very practical money, each tea brick was scored so that sections could be broken off for change, small purchases, or a quick pot of tea. Tea brick, China, mid 20th century

The tea brick shown here was produced in the People’s Republic of China sometime in the mid-20th century. It is in the Bank of Canada Museum’s National Currency Collection and can be seen in Zone 4 of our main gallery along with many curious and fascinating objects that have been used as money.

The Museum Blog

Speculating on the piggy bank

By: Graham Iddon

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon

Lessons from the Great Depression

By: Graham Iddon

Welcoming Newfoundland to Canada

By: David Bergeron