Coins from a nation that wasn’t: Araucania and Patagonia

By David Bergeron, Curator

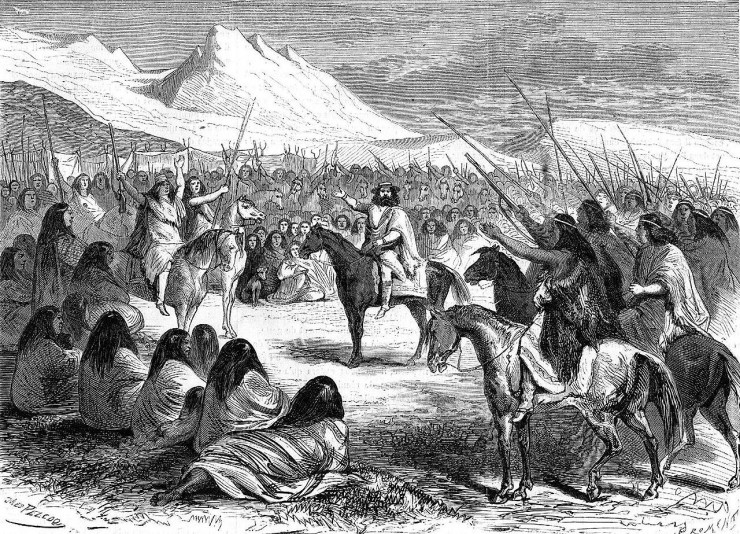

D’Antoine de Tounens in a meeting with the Mapuche people of Patagonia. (Wikimedia Commons, Jules Peco?)

It is not unusual for “micro-nations”— city-states, principalities or minor kingdoms—to produce their own currency. Having a national currency is one way that a fledgling nation can promote its independence—sometimes before there even is a nation. But this coin, from a purely conceptual country in South America, is most intriguing for the history it now represents: the attempt of an indigenous people to establish their own nation in the face of colonization. Even more intriguing, what’s stamped on the coin implies this imaginary nation had already been colonized–by France.

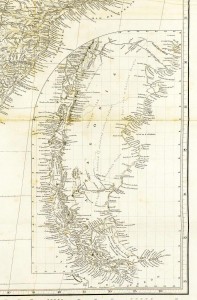

Patagonia from the survey by the British ships Adventure and Beagle. (Wikimedia Commons, John Arrowsmith, 1842)

In the middle of the 19th century, a French lawyer and adventurer named d’Antoine de Tounens became fascinated by the Mapuche people of the Patagonia region of South America. The Mapuche were struggling to protect their ancestral lands, their identity and their culture from colonial expansion by the governments of Chile and Argentina. De Tounens went to Chile in 1858 to meet the Mapuche, whom he admired for what he regarded as their heroic resistance, and took up their campaign for self‑determination and sovereignty. In co-operation with their leaders, de Tounens drafted a constitution for “Araucania and Patagonia”, a region located in the southern half of modern Chile and Argentina. They declared the district a kingdom and de Tounens was named as its first monarch. The Chilean government arrested him in 1862, put him on trial and declared him insane. Narrowly avoiding execution, de Tounens was deported to France.

The National Currency Collection possesses three 2-centavo coins minted for Araucania and Patagonia in 1874. What is so curious about these coins is that they claim this potential nation for France. The legend on the reverse reads “NOUVELLE FRANCE / DOS / CENTAVOS / 1874". De Tounens appeared to have baptized the nation as part of New France, yet this designation is seen nowhere else but on the coins. The coins don’t originate from South America but by some accounts may have been struck, presumably at de Tounens’ request, in Belgium.

De Tounens intended to take the coins back with him to Patagonia to help re-establish his kingdom. Although he returned and failed on several occasions, a number of countries did choose to recognize his fledgling state. But it was not to be. In 1878, Orélie-Antoine de Tounens (as his magisterial name was) died in France as the exiled King of Araucania and Patagonia. A successor to the office of Royal Highness to the Crown of Araucania and Patagonia (in exile) still lives in France today–Prince Antoine IV.

The Museum Blog

Johnson’s Counterfeits

By: David Bergeron

Johnson’s entire family, two girls and five boys, was involved in the counterfeiting operation: dad made the plates, the daughters forged the signatures and the boys were learning to be engravers.

The Reluctant Bank Note

By: Graham Iddon

Among 1975 $50 bill’s various design proposals were three images, three thematic colours and even three printing methods.

Nominating an Icon for the Next $5 Bank Note

By: Graham Iddon

Using a Bank of Canada Museum lesson plan, nearly 200 students told us who they thought should be the bank NOTE-able Canadian on our new $5 bill.

The “Streak of Rust” and the King of Newfoundland

By: David Bergeron

Reid was on the verge of ruin, yet insisted on continuing railway construction. Suffering huge losses, and with no credit or cash resources, Reid issued wage notes to pay his employees.

Retired Cash

By: Graham Iddon

In January 2021, 17 of our old bank notes will lose their legal tender status—what does that mean?

The Fisher, the Photographer and the Five

By: Graham Iddon

There’s little doubt that the BCP45 is lovingly preserved today partly thanks to being immortalized on this beautiful blue five-dollar bill.

Where Futurists Feared to Tread

By: Graham Iddon

Among the laser pistols, hover cars and androids of science fiction, there’s an elderly elephant in the room: money.