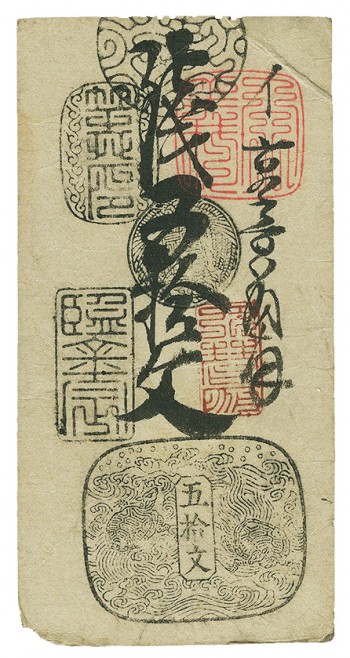

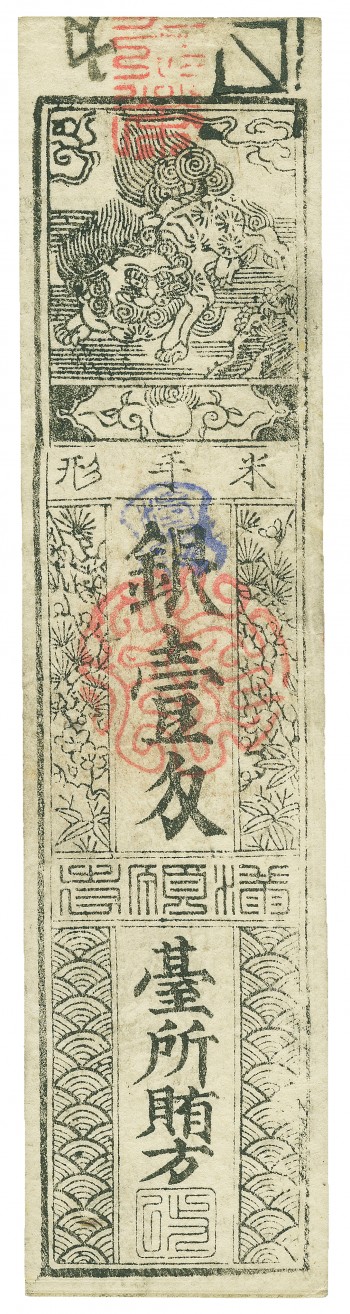

Often referred to as “bookmark money” because of their narrow, vertical format, Japanese hansatsu are among the world’s most distinctive currencies. The name of the notes is derived from the territories (han) of cash-starved local feudal lords (daimyos) who, when faced with meagre revenues, issued their own paper notes (satsu) in place of precious metal coins.

From the early days of the Tokugawa Shoganate (the feudal military government) in the 17th century until the mid-19th century, thousands of these notes were issued by nobles, towns, religious groups, companies and merchants. In an attempt to promote its own coinage, the central government banned the issue of hansatsu in 1707, nearly financially ruining the daimyos. The government abolished the ban in 1730.

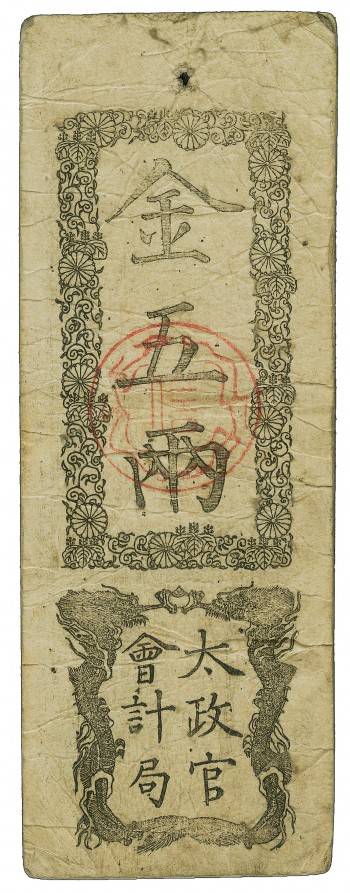

Designs printed on the notes included images of local flora and fauna such as chrysanthemums and storks. Other notes featured waves (nami) and mythical figures such as Diakoku, the god of wealth. He is shown seated atop two bags of grain—early bartering items in Japan. Notes were denominated in weights of gold (kin), silver (gin) or copper (dö). Sometimes they even represented such differing commodities as charcoal or umbrellas.

With the end of feudal military rule and the restoration of the monarchy in 1867, most private notes were pulled from circulation. Though significantly devalued, some notes issued by more financially solvent groups remained in circulation until the government was able to supply adequate quantities of coins. It wasn’t until 1879 that the last of the hansatsu were replaced by government issued notes. The first paper currency issued by the new government resembled hansatsu but was later replaced by notes of a decidedly more Western appearance.

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2025 edition

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

By: Graham Iddon

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

By: Graham Iddon

Speculating on the piggy bank

By: Graham Iddon