Money and holiday traditions

These days, while gift cards comprise a staggering percentage of gift giving, cash doesn’t always have the same cachet. In some quarters it seems a bit thoughtless; not where you want to land when it’s the thought that counts. But before you start sliding that pretty polymer note back into your wallet, why not reconsider? You’ll have history on your side. When the Three Wise Men trudged across the desert to honour the Christ Child, Gaspar and Balthasar brought frankincense and myrrh: the era’s versions of really pricey bath salts and essential oils. On the other hand, their third colleague, Melchior, brought gold. Now, did Balthasar then exchange a disapproving glance with Gaspar behind Melchior’s back for honouring the child with the first-century wad of cash? I think not, for gold and currency have held a deeply significant place in the holiday gift-giving practices of Christian, Jewish and Muslim traditions (not to mention the obscure roots of pagan practices).

The Three Wise Men in a detail of Mary and Child Surrounded by Angels, a 526AD mosaic at the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons: Nina-no)

Consider, for example, one of the stories that have sprung up around St. Nicholas. Sixteen centuries before he got a makeover and became an elf employer and Xbox distributer, the story goes, the future saint was a well‑off orphan and later a bishop who had become a passionate philanthropist. He took pity on a family lately brought down in the world: a widower with three daughters. The widower didn’t have the funds to provide dowries for his daughters, and the young women were at risk of being sold into slavery. Anonymously, Nicholas gave them each a quantity of gold by variously tossing it through an open window or climbing down the chimney. By either (somewhat questionable) method, the money ended up in the women’s stockings and shoes as they hung on the mantel to dry. Okay, so it’s a stretch; but a fun tale nevertheless. Note that Nicholas didn’t give them spa days or infinity scarves, rather it was cold, hard cash. This was also fourth-century Turkey, so elves and reindeer were rather thin on the ground.

A detail of The Story of St. Nicholas by Fra Angelico, 1437. The Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons: Yorck Project)

The holiday traditions most of us enjoy are a grand mélange of Pagan, secular and theistic practices. In the Polish tradition, coins hidden beneath a plate at Christmas dinner brought wealth to the finder, Ukrainians finding spiderwebs (especially gold ones in trees) are to be blessed with wealth, and Czechs might place fish scales under your Christmas dinner plate to encourage good fortune. Every prop in the holiday drama generally has some sort of symbolic meaning—evergreen trees: life in the dead of winter, holly: Christ’s crown of thorns, the dreidel: Jewish resistance to oppression. Money, on the other hand, only seems to symbolize itself.

But the strangest holiday wealth tradition of all is from Catalonia. Catalans, an ethnic group within northern Spain, feature a curious addition to their sprawling crèche scenes. Tucked into some discreet part of Bethlehem is Caganer, a little fellow squatting down to bless the earth with his “fertilizer” to ensure a good harvest and, therefore, wealth and good fortune.

Caganer blessing the earth with his gift of fertilizer for a good harvest and wealth.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons: Slastic)

In an English household, you’re more likely to find your wealth in your food. In the English traditions, the Christmas pudding evolved from a medieval meat pie preserved with dried fruits to a richly delicious, brandy-soaked dessert with a hidden treat- coins to bring wealth and luck to those who find them. It may likely bring luck to their dentists if they aren’t careful, but this tradition is alive and well. The Royal Australian Mint offers the “Christmas Pudding Coin Pack”—a set of vintage sixpence and threepence coins marketed specifically for hiding in Christmas puddings.

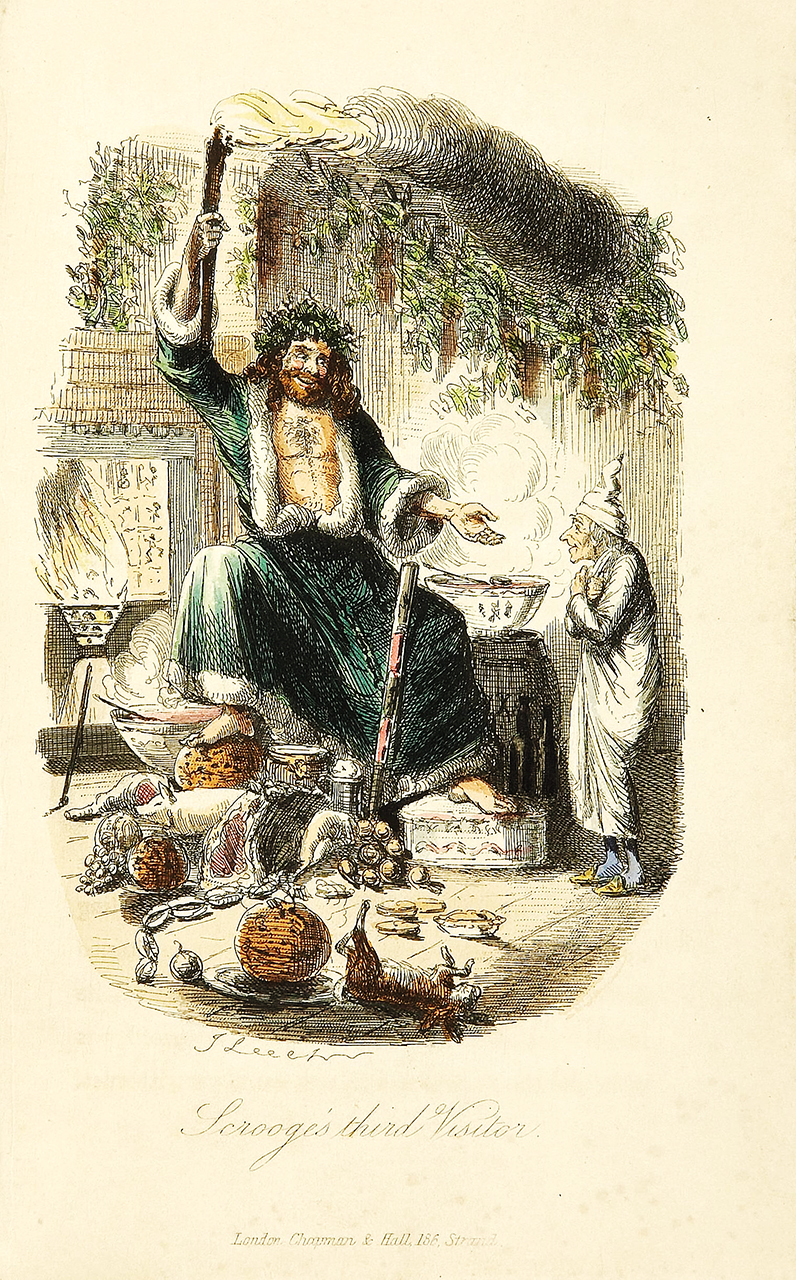

Front and centre of the Ghost of Christmas Present is a spherical Christmas pudding. From the 1843 first edition of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons: John Leech)

Though you cannot bake them into your plum pudding, we at the Museum naturally advocate crisp, colourful and beautifully designed Canadian polymer bank notes for holiday giving. Remember, you’ll be in good company, and, anyway, finding myrrh is always a problem this late in the season.

Happy Holidays from the Bank of Canada Museum.

The Museum Blog

Whatever happened to the penny? A history of our one-cent coin.

By: Graham Iddon

Good as gold? A simple explanation of the gold standard

By: Graham Iddon

Speculating on the piggy bank

By: Graham Iddon

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon

Lessons from the Great Depression

By: Graham Iddon

Welcoming Newfoundland to Canada

By: David Bergeron

New Acquisitions—2023 Edition

Mo’ money, mo’ questions

Understanding cryptocurrencies

By: Graham Iddon

A checkup on cheques

By: David Bergeron

The Scenes of Canada series $100 bill

By: Graham Iddon

Caring for your bank notes

By: Graham Iddon