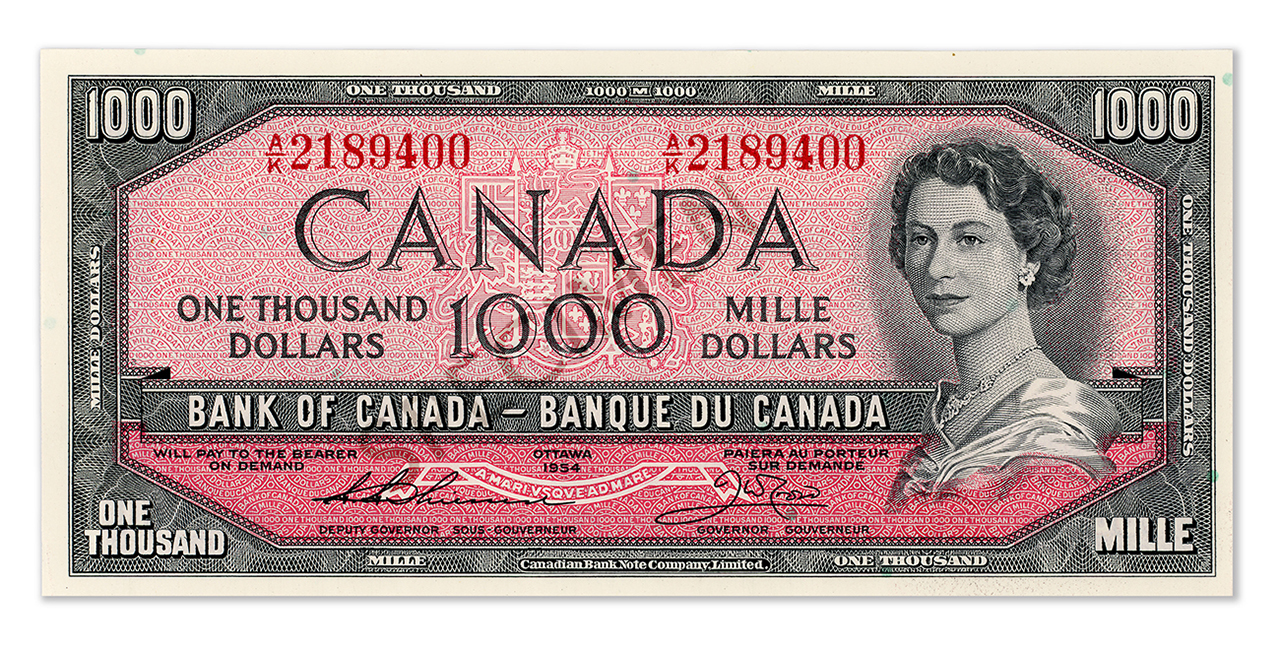

The 1969 Scenes of Canada bank note series was the first Bank of Canada series not to include a $1,000 bill. In the mid 60s, high denomination notes were in such low circulation that Governor Louis Rasminsky and the Minister of Finance discussed the possibility of actually dropping the denomination altogether. They elected instead to just continue circulating the 1954 notes, but not before two models (design mock-ups) had already been proposed for the back of a new $1,000 note. They were both produced by the U.K. printing firm of De La Rue who were responsible for all the face and back models of the ’69 series.

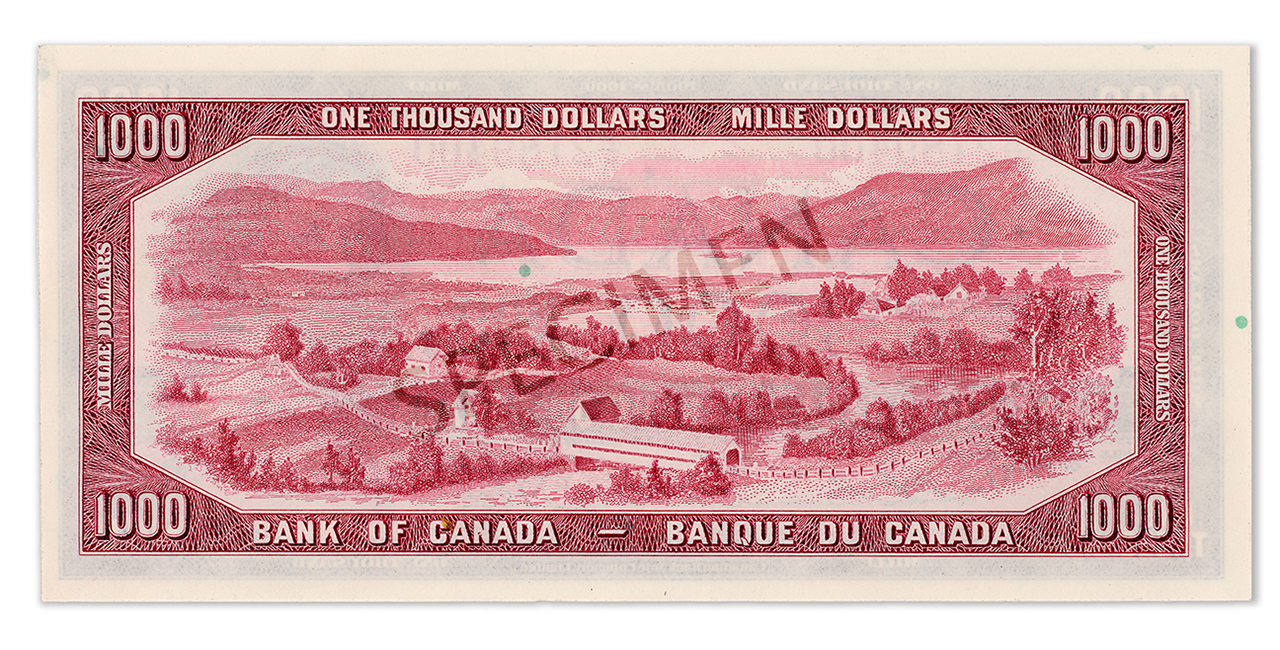

The first model was in keeping with the series theme of introducing human progress into Canadian vistas. Its vignette was of a stretch of highway through the Laurentian Mountains near Val-Morin, Quebec. Judging by the cars on the road, the photo appeared to have been taken in the 1950s. But during the process of preparing the original image to become an engraving, the cars were removed. Vehicles (boats) were prominently featured on 4 other denominations in the series, so this removal is a mystery. For the production of the models for this bill, De La Rue placed the highway vignette inside the border art from the $20 bill, the first note of this series to be issued.

Though meant for the back of the $1,000 note, De La Rue prepared this model using the framing artwork of the $20 note. (NCC 1993,57,16)

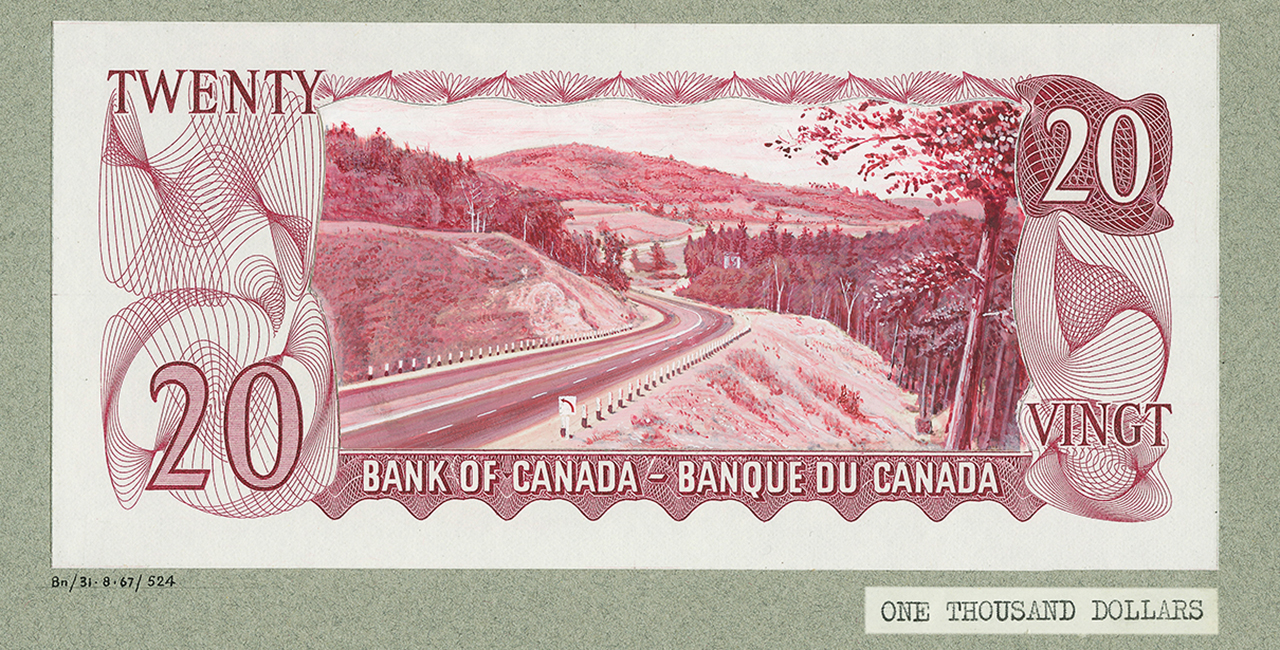

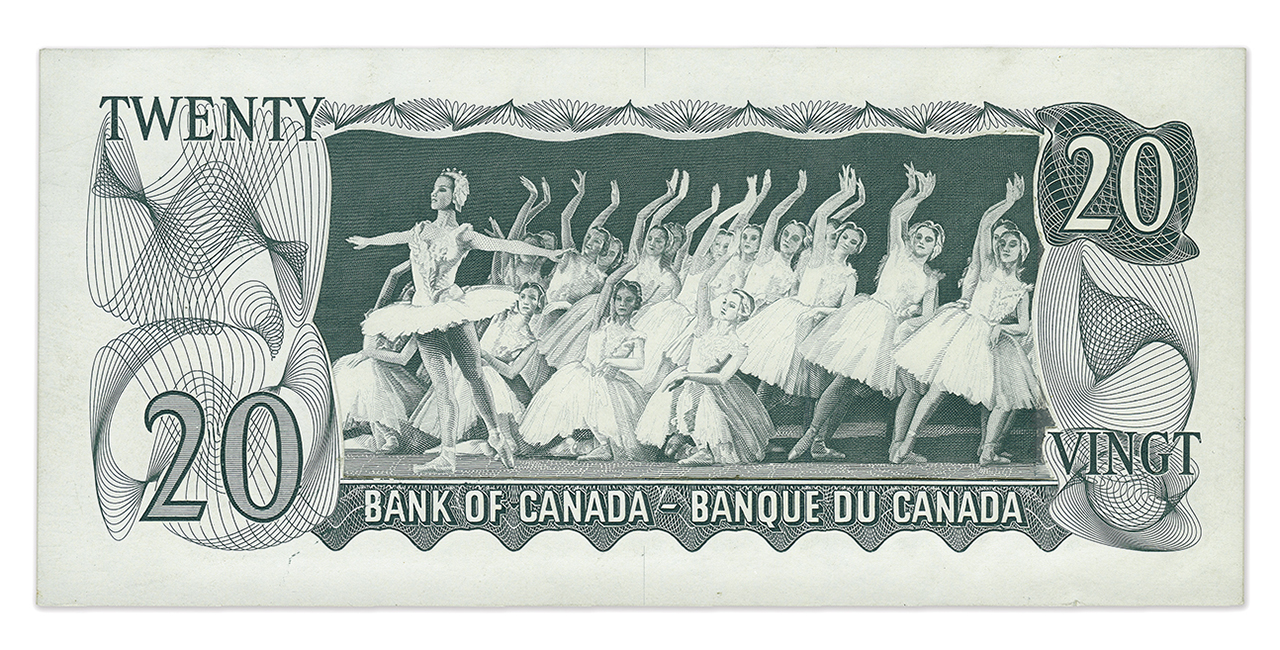

The second model produced by De La Rue represented a significant departure from the rest of the series in that it didn’t show a dramatic vista but featured people. There were people on the backs of other denominations (notably the $2) but in a purely circumstantial way—as features of a greater scene. The image proposed by De La Rue this time was of the dancers of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet performing a scene from Swan Lake. A highly detailed engraving by master engraver George Gundersen of the British American Bank Note Company, the ballet vignette would have been the first time that recognizable human faces appeared on the back of a Bank of Canada note. But it was not to be, and no known model exists for the face of this note.

The company of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet as featured in another test engraving. Again, the $20 is used as a framework model. (NCC 2000,22,1)

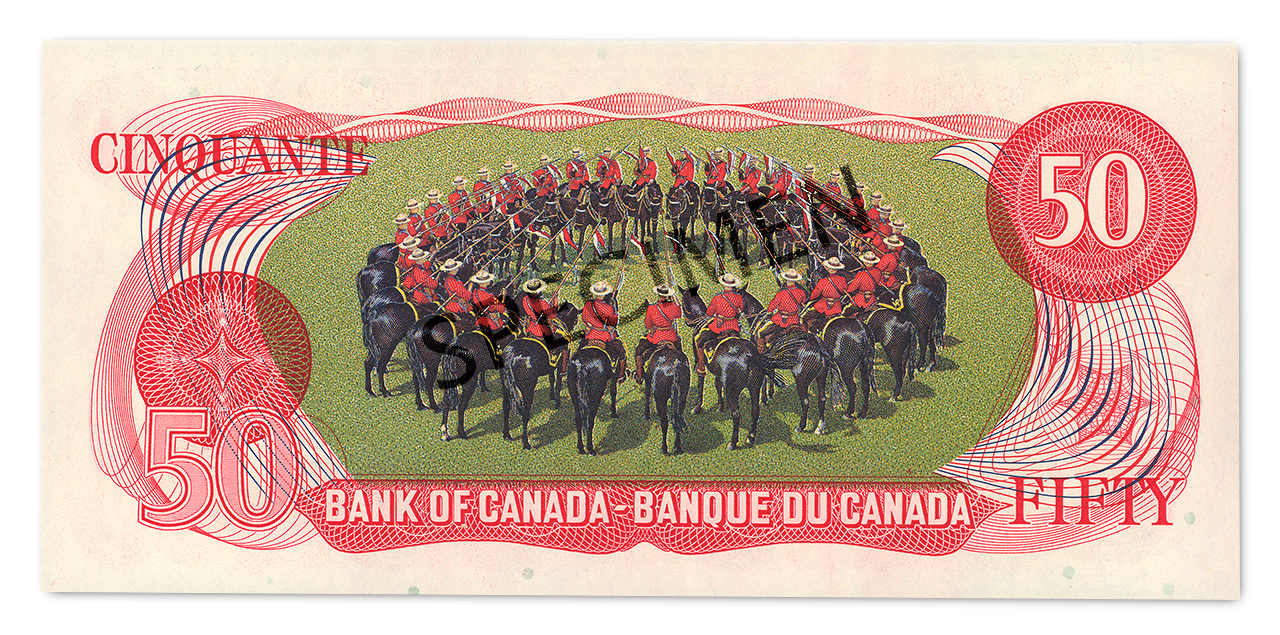

Later, the ballet vignette was proposed for the $50 note and Gundersen suggested a colour change to a bright red as the slate grey that was originally chosen made the engraving somewhat lifeless. However, prompted by the 1973 RCMP Centennial, it was decided to instead choose an image of the Musical Ride for the back of the $50 bill. Sadly, the ballet image was never issued.

The $1,000 bill would return in 1992 with a pair of pine grosbeaks on the back. There would be no more $1,000 notes issued after 2000.

The RCMP Musical Ride replaced the ballet in the $50 bill design and became one of Canada’s most popular and memorable bank notes. (NCC 1975,70,1)

The Museum Blog

New acquisitions—2024 edition

Money’s metaphors

Treaties, money and art

Rai: big money

By: Graham Iddon

Lessons from the Great Depression

By: Graham Iddon

Welcoming Newfoundland to Canada

By: David Bergeron